By Colonel Henry Inman in 1897

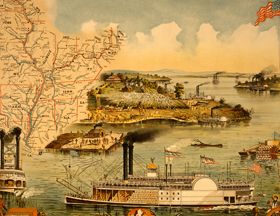

Mississippi River steamboats

In 1817, the navigation of the Mississippi River was begun. On August 2, the steamer General Pike arrived at St. Louis, Missouri. The Independence was the first boat to ascend the Missouri River; she passed Franklin, Missouri, on May 28, 1819, where a dinner was given to her officers. The following month, the steamers Western Engineer Expedition and R. M. Johnson came along, carrying Major Stephen Long’s scientific exploring party, bound for the Yellowstone River.

At that time, the quaint old cities of far-off Mexico were forbidden to foreign traders, except for the favored few who successfully obtained permits from the Spanish government. In 1821, however, the Mexican War of Independence crushed the mother country’s power and established Mexico’s freedom. The embargo upon foreign trade was at once removed, and the Santa Fe Trail, for untold ages only a simple trace across the continent, became the busy highway of relatively great commerce.

Santa Fe traders soon realized the benefits of river navigation — for it enabled them to shorten the distance which their wagons had to travel in going across the plains — and they began to look out for a suitable place as a shipping and outfitting point higher up the river than Franklin, Missouri which had been the initial starting town.

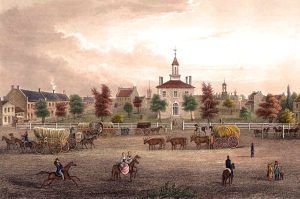

By 1827 trading posts had been established at Blue Mills, Fort Osage, and Independence, Missouri. The first-mentioned place, situated about six miles below Independence, soon became the favorite landing. The exchange from wagons to boats settled and defied all efforts to remove the trade headquarters from there for several years. Independence, however, being the county seat and the more prominent place, succeeded in its claims to be the more suitable locality, and as early as 1832, it was recognized as the American headquarters and the excellent outfitting point for the Santa Fe commerce, which it continued to be until 1846 when the breaking temporarily suspended the traffic out of the Mexican-American War.

Independence was not only the principal outfitting point for the Santa Fe Traders but also that of the great fur companies. That influential association used to send out larger pack-trains than any other parties engaged in the traffic to the Rocky Mountains; they also employed wagons drawn by mules and loaded with goods for the Indians with whom their agents bartered, which also on their return trip, transported the skins and pelts of animals procured from the Indians. The articles intended for the Indian trade were always purchased in St. Louis, Missouri, and usually shipped to Independence, consigned to the firm of Aull and Company, who outfitted the traders with mules and provisions. In fact, anything else required by them.

Several individual traders would frequently form joint caravans and travel in company for mutual protection from the Indians. After having reached a 50-mile limit from the State line, each trader had control of his men; each took care of a certain number of the pack animals, loaded and unloaded them in camp, and had general supervision of them.

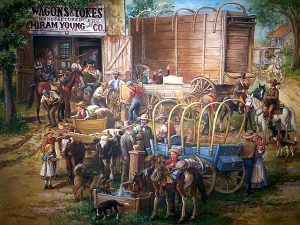

Frequently, there would be 300 mules in a single caravan, carrying 300 pounds apiece. Thousands of wagons were also sent out from Independence annually, each drawn by twelve mules or six yokes of oxen and loaded with general merchandise.

There were no packing houses in those days nearer than St. Louis, and the bacon and beef used in the Santa Fe trade were furnished by the farmers of the surrounding country, who killed their meat, cured it, and transported it to the town where they sold it. Their wheat was also ground at local mills, and they brought the flour to market, together with corn, dried fruit, beans, peas, and kindred provisions used on the long route across the plains.

Independence soon became the best market west of St. Louis for cattle, mules, and wagons. As the acknowledged headquarters, it employed several thousand men, including the teamsters and packers on the Santa Fe Trail. The wages and rations varied from $25 to $50 a month. The price for hauling freight to Santa Fe was $10 for every 100 pounds, each wagon earning from $500-$600 every trip, which was made in 80-90 days; some fast caravans made quicker time.

The merchants and general traders of Independence in those days reaped a grand harvest. Everything to eat was in constant demand; mules and oxen were sold in great numbers monthly at excellent prices and always for cash, while any good stockman could readily make from $10-$50 a day.

Hiram Young’s Wagon Shop in Independence, Missouri, painting by Cheryl Harness, 2011.

One of Independence’s most prominent manufacturers and most enterprising young men at that time was Hiram Young, an African-American man. Besides making hundreds of wagons, he made all the ox-yokes used in the Santa Fe trade, 50,000 annually during the 1850s and until the breaking out of the Civil War. The forward yokes were sold at an average of $1.25, and the wheel yokes for $2.25.

The freight transported by the wagons was always very securely loaded; each package had its contents marked on the outside. The wagons were heavily covered and tightly closed. Every man belonging to the caravan was thoroughly armed and ever on the alert to repulse an attack by the Indians.

Sometimes at the crossing of the Arkansas River, the quicksands were so bad that it was necessary to get the caravan over in a hurry; then, 40-50 yoke of oxen were hitched to one wagon, and it was quickly yanked through the treacherous ford. However, this was not always the case; it depended upon the stage of the water and recent floods.

After the close of the Mexican-American War, the freight business across the plains increased dramatically. The possession of the country by the United States gave a fresh impetus to the New Mexico trade, and the traffic then began to be divided between Westport and Kansas City. Independence lost control of overland commerce, and Kansas City commenced its rapid growth. Then came the discovery of gold in California, which increased business westward; thousands of men and their families crossed the plains and the Rocky Mountains, seeking their fortunes in the new El Dorado. The Old Trail was the highway of an enormous pilgrimage, and Independence and Kansas City became the initial emigration point.

In July 1850, an account of the first mail stage westward from Independence recorded:

“The Santa Fe line of mail stages left this city on its first monthly journey on July 1. The stages are got up in elegant style and are each arranged to convey eight passengers. The bodies are beautifully painted and made water-tight, with a view of using them as boats in ferrying streams. The team consists of six mules to each coach. The mail is guarded by eight men, armed as follows: Each man has at his side, fastened in the stage, one of Colt’s revolving rifles; in a holster below, one of Colt’s long revolvers, and in his belt a small Colt’s revolver, besides a hunting-knife; so that these eight men are ready, in case of attack, to discharge one hundred and thirty-six shots without having to reload. This is equal to a small army, armed as in the ancient times, and from the looks of this escort, ready as they are, either for offensive or defensive warfare with the Indians, we have no fears for the safety of the mails.

“The accommodating contractors have established a sort of base of refitting at Council Grove, Kansas, a distance of 150 miles from this city, and have sent out a blacksmith, and a number of men to cut and cure hay, with a quantity of animals, grain, and provisions; and we understand they intend to make a sort of traveling station there and to commence a farm. They also, we believe, intend to make a similar settlement at Walnut Creek next season. Two of their stages will start from here the first of every month.”

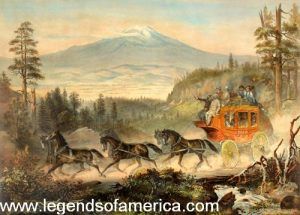

The monthly stages started from each end of the route at the same time; later, the service was increased to once a week, after a while, to three times, until in the early 1860s, daily stages were run from both ends of the route, and this was continued until the advent of the railroad. Each coach carried eleven passengers, nine closely stowed inside — three on a seat — and two on the outside on the boot with the driver. The fare to Santa Fe was $250, and the baggage allowance was limited to 40 pounds; all more than that cost 50¢ per pound. In this now seemingly large sum was included the board of the travelers, but they were not catered to in any extravagant manner; hardtack, bacon, and coffee usually exhausted the menu, save that at times, there was an abundance of antelope and buffalo.

Stagecoach with a guard sitting on top, protecting whatever wealth it might have been carrying. (1913)

There was always something exciting in those journeys from the Missouri River to the mountains in the lumbering Concord coach. There was a constant fear of meeting Indians. Then there was the playfulness of the sometimes drunken driver, who loved to upset his tenderfoot travelers in some arroyo long after the moon had sunk below the horizon.

It required about two weeks to make the trip from the Missouri River to Santa Fe, New Mexico, unless high water or a fight with the Indians made it several days longer. The animals were changed every 20 miles at first, but later, every ten, when faster time was made. What sleep was taken could only be had during sitting bolt upright because there was no laying over; the stage continued on night and day until Santa Fe was reached.

After a few years, the company built stations at intervals varying from ten miles to fifty or more; and there, the animals and drivers were changed, and meals furnished to travelers, which were always substantial, but never elegant in variety or cleanliness. Passengers were obliged to partake or go hungry for station meals that included a biscuit hard enough to serve as “round-shot” and a vile decoction called, through courtesy, coffee — but God help the man who disputed it!

Some stations, however, were notable exceptions, particularly in the mountains of New Mexico, where, aside from the bread — usually only tortillas, made of the blue-flint corn of the country — and coffee, composed of the saints may know what, the meals were excellent. The most delicious brook trout, alternating with venison of the black-tailed deer, elk, bear, and all the other varieties of game abounding in the region. The passenger cost was $1.

Thirteen years ago, I revisited the once well-known Kozlowski’s Ranch, a picturesque cabin at the foot of the Glorieta Mountains, about half a mile from the ruins on the Rio Pecos. The old owner was absent, but his wife was there, and although I had not seen her for 15 years, she remembered me well and at once began to lament the changed condition of the country since the advent of the railroad, declaring it had ruined their family with many others. I could not disagree with her view as I looked at the debris of former relative greatness around me. I recalled the fact that once Kozlowski’s Ranch was the favorite eating station on the Santa Fe Trail, where you were ever sure of a substantial meal — the main feature of which was the delicious brook trout, which were caught out of the stream which ran near the door while you were washing the dust out of your eyes and ears.

The trout have vacated the Pecos River; the ranch is a ruin and stands in grim contrast with the old temple and church on the hill, and both are monuments of civilizations that will never come again.

Weeds and sunflowers mark the once broad trail to Santa Fe, and silence reigns in the beautiful valley, save when broken by the passage of “The Flyer” of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad, as it struggles up the heavy grade of the Glorieta Mountains a mile or more distant.

Besides the driver, there was another employee — the conductor or messenger, as he was called. He had charge of the mail and express matter, collected the fares, and generally attended to the requirements of those committed to his care during the tedious journey; for he was not changed like the driver but stayed with the coach from its starting to its destination. Sometimes, 14 individuals were accommodated in case of emergency. Still, riding was crowded and uncomfortable, with no chance to stretch your limbs, save for a few moments at stations where you ate and changed animals.

In starting from Independence, powerful horses were attached to the coach — generally four in number; at the first station, they were exchanged for mules, and these animals hauled it the remainder of the way.

Drivers were changed about eight times in making the trip to Santa Fe. Some of them were comical fellows but full of nerve and endurance, for it required a man of nerve to handle eight frisky mules through the rugged passes of the mountains, when the snow drifted in immense masses, or when descending the curved, icy declivities to the base of the range. A cool head was essential, but frequent accidents occurred and sometimes were severe in their results.

A snowstorm in the mountains was a terrible thing to encounter by the coach; all that could be done was to wait until it had diminished, as there was no going on in the face of the blinding sheets of intensely cold vapor that the wind hurled against the sides of the mountains. All inside the coach had to sit still and shake with the freezing branches of the tall trees around them. However, a summer hailstorm was much more to be dreaded; for nowhere else on the earth do the hailstones shoot from clouds of greater size or with greater velocity than in the Rocky Mountains. Such an event invariably frightened the mules and caused them to stampede, and, to escape death from the coach rolling down some frightful abyss, one had to jump out, only to be beaten to a jelly by the masses of ice unless shelter could be found under some friendly ledge of rock or the thick limbs of a tree.

Nothing is more fatiguing than traveling for the first day and night in a stagecoach; however, one gets used to it, and the remainder of the journey is relatively comfortable. The only way to alleviate the monotony of riding hour after hour was to walk; occasionally, this was necessary by accident, such as breaking a wheel or axle or when an animal gave out before a station was reached. In such cases, however, no deduction was made from the fare collected in advance, so it cost you just as much whether you rode or walked. You could exercise your will in the matter, but you must not lag behind the coach; the Indians were constantly watching for such derelicts, and your hair was the forfeit!

In the worst years, when the Indians were most decidedly on the war trail, the government furnished an escort of soldiers from the military posts; they generally rode in a six-mule army wagon and were commanded by a sergeant or corporal, but, in the early days, before the army had concentrated at the various forts on the great plains, the stage had to rely on the courage and fighting qualities of its occupants, and the nerve and the good judgment of the driver.

If the latter understood his duty thoroughly and was familiar with the methods of the Indians, he always chose the cover of darkness in which to travel in localities where the danger from Indians was greater than elsewhere; for it is a rare thing in Indian warfare to attack at night. The early morning seemed to be their favorite hour when sleep oppressed most heavily, and the utmost vigilance was demanded.

One of the most confusing things to the novice riding over the great plains was the idea of distance; when mile after mile was traveled on the monotonous trail, with a range of hills or a low divide in full sight, yet hours rolled by and the objects seemed no nearer than when they were first observed. The reason for this is the absolute clearness of the atmosphere, such indescribable transparency of space through which distant objects are seen, that they are magnified and look nearer than they are. Consequently, the usual method of calculating distance and areas by the eye was ever at fault until custom and familiarity forced a new standard of measure.

Mirages, too, were of frequent occurrence on the great plains; some of the wonderful examples of the refracting properties of light. They assumed all manner of fantastic, curious shapes, sometimes ludicrously distorting the landscape; objects, like a herd of buffalo, for instance, though 40 miles away, would seem high in the air, often reversed and immensely magnified in their proportions.

Violent storms were also frequent incidents of the long ride. I remember one night, about 30 years ago, when the coach I and one of my clerks were riding to Fort Dodge, Kansas, was suddenly brought to a standstill by a terrible gale of wind and hail. The mules refused to face it and quickly turning around nearly overturned the stage, while we, with the driver and conductor, were obliged to hold on to the wheels with all our combined strength to prevent it from blowing down into a stony ravine on the brink of which we were brought to a halt. Fortunately, these fearful blizzards did not last very long; the wind ceased blowing violently in a few moments, but the rain usually continued until morning.

It usually happened that you either, at once, took a great liking for your driver and conductor or the reverse. Once, on a trip from Kansas City, nearly a third of a century ago, when another man and I were the only occupants of the coach, we entertained quite a friendly feeling for our driver; he was a good-natured, jolly fellow, full of anecdote and stories of the Trail, over which he had made more than 100 sometimes adventurous journeys.

When we arrived at the station at Plum Creek, the coach was a little ahead of time, and the driver who was there to relieve ours began to grumble at the idea of starting out before the regular hour. He found fault because we had come into the station so soon and swore he could drive where our man could not “drag a halter chain,” as he claimed in his boasting. We at once took a dislike to him and secretly wished that he would come to grief to cure him of his boasting. Sure enough, before we had gone half a mile from the station, he tumbled the coach into a sandy arroyo, and we were delighted at the accident. Finding ourselves free from any injury, we went to work and assisted him to right the coach — no small task; but we took great delight in reminding him several times of his ability to drive where our old friend could not “drag a halter-chain.” It was very dark; neither moon nor star was visible, the whole heavens covered with an inky blackness of ominous clouds, so he was not so much to blame.

The next coach was attacked at the crossing of Cow Creek by a band of Kiowa warriors. The Indians had followed the stage all that afternoon but remained out of sight until just at dark, when they rushed over the low divide and mounted on their ponies commenced to circle the coach, making the sand dunes resound with echoes of their infernal yelling, and shaking their buffalo-robes to stampede the mules, at the same time firing their guns at the men who were in the coach, all of whom made a bold stand but were rapidly getting the worst of it when fortunately a company of United States Cavalry came over the Trail from the west and drove the Indians off. Two of the men in the coach were seriously wounded, and one of the soldiers was killed, but the Indian loss was never determined, as they succeeded in carrying off both their dead and wounded.

Mr. William H. Ryus, who was a driver and messenger for 35 years and had many adventures, told me about the following incidents:

“I have crossed the plains 65 times by wagon and coach. In July 1861, I was employed by Barnum, Vickery, and Neal to drive over what was known as the Long Route, that is, from Fort Larned, Kansas to Fort Lyon, Colorado — 240 forty miles, with no station between. We drove one set of mules the whole distance, camped out, and made the journey, in good weather, in four or five days. In winter, we generally encountered a great deal of snow and very cold air on the bleak and wind-swept desert of the Upper Arkansas River, but we employees got used to that; only the passengers did any kicking. We had a way of managing them; however, when they got very difficult, all we had to do was to yell Indians! and that quieted them quicker than forty-rod whiskey does a man.

“We gathered buffalo chips to boil our coffee and cook our buffalo and antelope steak, smoked for a while around the smoldering fire until the animals were through grazing, and then started on our lonely way again.

“Sometimes the coach would travel for a hundred miles through the buffalo herds, never for a moment getting out of sight of them; often we saw fifty thousand to a hundred thousand on a single journey out or in. The Indians used to call them their cattle and claimed to own them. Like the white man, they did not take out only the tongue or hump and leave all the rest to dry upon the prairie but ate every last morsel, even to the intestines. They said the whites were welcome to all they could eat or haul away, but they did not like to see so much meat wasted, as was our custom.

“The Indians on the plains were not at all hostile in 1861-62; we could drive into their villages, where there were tens of thousands of them, and they would always treat us to music or war dance, and set before us the choicest of their venison and buffalo. In July 1862, Colonel Jesse Henry Leavenworth was crossing the Trail in my coach. He desired to see Satanta, the great Kiowa chief. The colonel’s father was among the Indians a great deal while on duty as an army officer, while the young colonel was a small boy. The colonel said he didn’t believe that old Satanta would know him.

“Just before the arrival of the coach in the region of the Indian village, the Comanche and the Pawnee had been having a battle. The Comanche had taken some scalps, and they were camping on the bank of the Arkansas River, where Dodge City, Kansas, is now located. The Pawnee had killed five of their warriors, and the Comanche were engaged in an exciting war dance; I think there were from twenty to thirty thousand Indians gathered there, men, women, and children of the several tribes — Comanche, Kiowa, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and others.

“When we came in sight of their camp, the colonel knew, by the terrible noise they were making, that a war dance was going on; but we did not know then whether it was on account of troubles among themselves or because of a fight with the whites, but we were determined to find out. If he could get to the old chief, all would be right. So, he and I started for the place whence the noise came. We met an Indian and the colonel asked him whether Satanta was there and what was going on. When he told us that they had had a fight and it was a scalp dance, our hair lowered; for we knew that if it was in consequence of trouble with the whites, we stood in some danger of losing our own scalps.

“The Indian took us in, and the situation, too; and conducted us into the presence of Satanta, who stood in the middle of the great circle, facing the dancers. It was out on an island in the stream; the chief stood very erect and eyed us closely for a few seconds, then the colonel told his own name that the Indians had known him by when he was a boy. Satanta gave one bound — he was at least ten feet from where we were waiting — grasped the colonel’s hand and excitedly kissed him, then stood back for another instant, gave him a second squeeze, offered his hand to me, which I, of course, shook heartily, then he gazed at the man he had known as a boy so many years ago, with a countenance beaming with delight. I never saw anyone, even among the white race, manifest so much joy as the old chief did over the visit of the colonel to his camp.

“He immediately ordered some of his young men to go out and herd our mules through the night, which they brought back to us at daylight. He then had the coach hauled to the front of his lodge, where we could see all that was going on to the best advantage. We had six travelers with us on this journey, and it was a great sight for the tenderfeet.

“It was about ten o’clock at night when we arrived at Satanta’s lodge, and we saw thousands of men and women dancing and mourning for their dead warriors. At midnight the old chief said we must eat something at once. So he ordered a fire built, cooked buffalo and venison, setting before us the very best that he had; we furnishing canned fruit, coffee, and sugar from our coach mess. There we sat, talked, and ate until morning; when we were ready to start off, Satanta and the other chiefs of the various tribes escorted us about eight miles on the Trail, where we halted for breakfast, they remaining and eating with us.”

Colonel HenryLeavenworth was on his way to assume command of one of the military posts in New Mexico; the Indians begged him to come back and take his quarters at either Fort Larned or Fort Dodge in Kansas. They told him they feared their agent was stealing their goods and selling them back to them, while if the Indians took anything from the whites, a war was started.

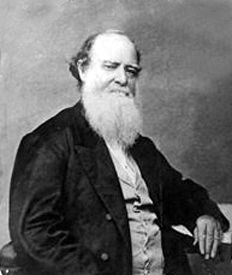

Albert Gallatin “A.G.” Boone

Colonel Albert G. Boone, the grandson of Daniel Boone, had made a treaty with these same Indians in 1860, and it was agreed that he should be their agent. It was done, and the entire Indian nations were restful and kindly disposed toward the whites during his administration; anyone could then cross the plains without fear of molestation. In 1861, however, Judge Wright of Indiana, a member of Congress at the time, charged Colonel Boone with disloyalty and succeeded in having him removed.

Majors, Russell, and Waddell, the great government freight contractors across the plains, gave Colonel Boone 1400 acres of land, well improved, with some fine buildings, about 25 miles east of present-day Pueblo, Colorado. It was christened Booneville, and the colonel moved there. In the fall of 1862, 50 influential Indians of the various tribes visited Colonel Boone at his new home and begged him to return to them and be their agent. He told the chiefs that the President of the United States would not let him. Then they offered to sell their horses to raise money for him to go to Washington to tell the Great Father what their agent was doing and to have him removed, or there would be trouble. The Indians told Colonel Boone that many of their warriors would be on the plains that fall, and they were declaring they had as much right to take something to eat from the trains as their agent had to steal goods from them.

Early in the next year’s winter, a small caravan of eight or ten wagons traveling to the Missouri River was overhauled at Nine Mile Ridge, about 50 miles west of Fort Dodge, Kansas, by a band of Indians who asked for something to eat. The teamsters, thinking they were hostile, believed it would be a good thing to kill one of them anyhow, so they shot an inoffensive warrior, after which the train moved on to its camp, and the trouble began. Every man in the outfit, except for one teamster, who luckily got to the Arkansas River and hid, was murdered, the animals carried away, and the wagons and contents destroyed by fire.

This foolish act by the master of the caravan was the cause of a long war, causing hundreds of atrocious murders and the destruction of a great deal of property along the whole Western frontier.

In the fall of 1863, Mr. Ryus was the messenger or conductor in charge of the coach running from Kansas City to Santa Fe. He said:

“It then required a month to make the round trip, about 1800 miles. On account of the Indian war, we had to have an escort of soldiers to go through the most dangerous portions of the Trail; and the caravans all joined forces for mutual safety besides having an escort.

“My coach was attacked several times during that season, and we had many close calls for our scalps. Sometimes the Indians would follow us for miles, and we had to halt and fight them, but as for myself, I had no desire to kill one of the outraged men, who had been swindled out of their just rights.

“I know of but one occasion when we were engaged in a fight with them when our escort killed any of the attacking Indians; it was about two miles from Little Coon Creek Station, where they surrounded the coach and commenced hostilities. In the fight, one officer and one enlisted man were wounded. The escort chased the band for several miles, killed nine, and got their horses.”

The old stagecoach days were times of Western romance and adventure. In many places on the line of the Trail, where the hard hills had not been subjected to the plow, the deep ruts cut by the lumbering Concord coaches could still be seen for years.

By Colonel Henry Inman, 1897. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2023.

Also See:

Early Traders on the Santa Fe Trail

Santa Fe Trail – Highway to the Southwest

Stagecoaches of the American West

About the Author: Excerpted from the book, The Old Santa Fe Trail by Colonel Henry Inman, 1897. Note: The text is not verbatim, as minor edits have been made throughout the tale. Henry Inman was well known as an officer in the U.S. Army and an author dealing with subjects of the Western plains. During the Civil War, Inman was a Lieutenant Colonel, and afterward, he won distinction as a magazine writer. He wrote several books, including his Old Santa Fe Trail, Great Salt Lake Trail, The Ranch on the Ox-hide, and other similar books dealing with the subjects he knew so well. Colonel Inman left several unfinished manuscripts at his death in Topeka, Kansas, on November 13, 1899.