By William Eleroy Curtis, 1883

Danger always develops heroes, as it develops recklessness and ruffianism, and a disregard for the value of human life that is almost incredible. But in the countless numbers of hunters, trappers, guides, and scouts whose adventures are a part of the history of the Santa Fe Trail, there were some characters who deserve more than a passing glance from the eyes of the denizens of the civilized world. For courage, nerve, endurance, intelligence and manliness, Kit Carson stands at the head of the class he so honorably represented. His biography has been repeatedly written, and his public services have been extensively extolled, but too much cannot be said in praise of his virtues as a man, and his abilities as a frontiersman. If he had been permitted to enjoy the ordinary advantages and associations of civilized life he would have stood among the world’s leaders, but he made the most of his privileges and was the greatest among men of his type and occupation.

Kit Carson Drawing

The Kit Carson of the imagination was a sort of Wild Bill, a frontier Hercules with a dozen revolvers at his belt, an enormous beard, the swagger of a Pirate King, and a voice like that of a roused lion. The actual Kit Carson was a plain, simple, quiet, silent, unobtrusive man, below medium height, slender in physique, of fair complexion, with a small hand and foot, a pleasant face, curly brown hair, clear hazel eyes, little or no beard, a soft voice, and manners as gentle as a woman’s. He was the hero of a hundred desperate adventures, killed more Indians than he could possibly remember, guided more important expeditions than any other man ever did, rescued many people from a captivity that was worse than slavery, and had a better knowledge of plainscraft than any of his contemporaries or successors; but for all this, he was no boaster, was indifferent to popularity, avoided notoriety, blushed when praised and wept at the sight of human suffering. It is truly said of him that he never had a quarrel on his own account, and never took the life of a man except in self-defense or as a measure of justice. He was not a profane man, and was strictly temperate, nor had he the loose habits that characterize the ordinary frontiersman. The word fear had no meaning for him, and his composure and self-confidence under difficulties were phenomenal. He was a splendid horseman and an unerring shot; his knowledge of Indian character was never surpassed, and everyone who had to do with him commended Kit Carson as the ideal scout and the best guide ever upon the plains.

General John C. Fremont said of him: “Carson while traveling scarcely ever spoke, but his keen eye was continually examining the country, and his whole manner was that of a man deeply impressed with a sense of responsibility. He never laughed or joked, even by the campfire, but was always watchful for the comfort of other people. He ate but twice a day, at morning and night, and was strictly temperate. In an Indian country, the mule is the best sentry, and Carson always slept with his mule tied to his saddle. A braver man than Carson perhaps-never lived; in fact, I doubt if he ever knew what fear was, but with all this, he exercised great caution. While arranging his bed for the night, his saddle, which he always used as a pillow, and to which the lariat of his mule was always tied, was disposed of in such a way as to form a barricade for his head. His pistols, half-cocked, were laid above it, and his trusty rifle reposed beneath the blanket by his side, where it was not only ready for instant service but perfectly protected from the damp.”

Kit Carson was born in Kentucky but went to Missouri with his parents when a child when that State was the extreme frontier, and only two or three years after it had been ceded by the French to the United States as a part of Louisiana. His father was a saddler, and Kit learned that trade. When he was about 16 years old, a party of traders for Santa Fe came along and he joined them, crossing the plains with a score of men, leading a pack mule heavily laden with goods for the Santa Fe market. He did not return with them, however, but went to Taos, New Mexico with a hunter and trapper by the name of Kin Kade, a Spaniard who was very highly educated, and from whom Kit learned the Spanish language, and much other valuable knowledge. His association with Kin Kade was practically all the education he ever received. A few years afterward he joined a party of traders and returned with them to Missouri, and from that time on until he joined General John Fremont in 1842, his life was spent as a guide on the plains, and as a hunter and trapper in the mountains under the direction of the Hudson Bay Company, which had its headquarters in the Rocky Mountains.

In their employ, he went in charge of parties of men, during each winter, through all the hunting and trapping regions between the Missouri River and the Pacific Ocean, and during the summer he guided trains of traders and emigrants over the plains. He came to know every valley and mountain stream, every spring upon the prairies, and his natural instincts as a scout gave him great value. His adventures have filled volumes, and his name and the incidents of his life are more familiar to schoolboys than those of some of the Presidents of the United States. He guided Fremont on both of his expeditions, and the two men became fast friends.

Lucien B. Maxwell

During the Mexican-American War, Fremont made Carson Lieutenant of his battalion of Mountaineers, and in 1846, when it became necessary for the “Path-finder” to send dispatches from California to Washington, he entrusted them to Carson, who carried them through the lands of hostile Indians, and more hostile Mexicans, reaching Washington in good time, where he remained for several weeks, the guest of Senator Thomas H. Benton, the father-in-law of General Fremont. This feat of Carson’s was unprecedented, and although his fame was already great, it made him a hero, and he received marked attention from all the distinguished men of the Capitol. Mrs. Jessie Benton Fremont, who was then the leading belle of Washington, met him at the depot and escorted the blushing trapper, who had scarcely ever seen the inside of a civilized house, to her own magnificent residence. He was a lion in society during his stay in Washington, under the patronage of Mrs. Fremont, and is said to have won the admiration of all by his native manliness and inborn gentility. President Polk made him a lieutenant in the United States Regular Army and sent him back across the plains with an escort of cavalry. The jealousy of the army officers at Washington was such that the Senate refused to confirm his appointment, and when Carson learned of it, he dismissed his escort and retired to his home in Taos, where he joined his old chum, Lucien B. Maxwell, and established a ranch on what was known as the Maxwell Land Grant.

He afterward kept a store at Taos, New Mexico under the firm name of Maxwell & Carson, but was not adapted to mercantile life, and did not succeed very well, so he returned to sheep raising, and remained on his ranch until the rebellion, when he volunteered as a private, and rose to the command of a Colorado regiment, performing gallant and valuable service for the Union.

After the war, “General” Carson, as he was then called, was appointed agent for the New Mexican Indians, and served in that capacity until his death, making a journey to Washington with a party of Apache chiefs in 1867.

He died in 1868, at Fort Lyon, Colorado, near where Bent’s old fort used to be, and across the river from the town of Las Animas, in the 60th year of his age. The cause of his death was traced back to a fall he received eight years before when his mule slipped and threw him upon a pile of rocks. He was originally buried at Fort Lyon, but his body was afterward removed to the old cemetery near Taos, New Mexico.

San Francisco Street in Santa Fe, New Mexico

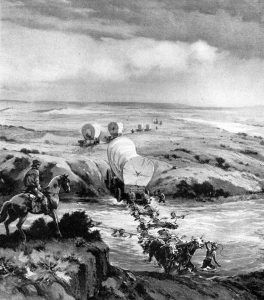

The story of the Santa Fe Trail that has been told more often than any other is about the famous ride of François (Frank) Aubry from Santa Fe, New Mexico to Independence, Missouri, 780 miles, in five days and 16 hours, his own beautiful mare, “Nellie,” having carried him the first 150 miles without a stop, except for food and water. Aubry was a French Canadian, first a guide, then a trader. Like Kit Carson, he was a man of medium stature and slender proportions, but he had iron nerves, great resolution, and indomitable persistence. As a pioneer, guide, and trader, he did much that is worthy of mention, but the great feat for which he is remembered was his famous ride. The circumstances were as follows:

Aubry had gone out early in the spring of 1848, with a large amount of goods to Santa Fe. As the American troops were then in possession of the country, our merchants, relieved from the interference of those unscrupulous plunderers, the Mexican customhouse officers, found increased competition, but greater facilities for their trade. The business was, therefore, “booming,” and Aubry found no difficulty in getting rid of his stock at an advance of over 100 percent upon his original investment. ‘Knowing the favorable state of the market, and the description of merchandise best suited to its wants, he determined to attempt a hitherto unheard-of enterprise, by making a second trip to St. Louis, and bringing out another stock before cold weather should cease the communications between Santa Fe and the settlements. To accomplish this, Aubry allowed himself but eight days to traverse the whole Santa Fe Trail, most of which was dangerous on account of the Indians. Having laid his plans and announced his scheme, he, with four companions, and a small but carefully selected herd of horses, set out upon their trip. They rode hard, but the leader outstripped his men, and by the time Aubry had reached the “crossing of the Arkansas River,” which is generally considered about half-way, he found himself, with his last horse given out, alone, and on foot. Undaunted, however, he pushed on, and reached Mann’s Fort, some 15-20 miles from the ford. Here, he procured a remount, and then, without waiting to rest, or scarcely to eat, he once more took the trail. Near Pawnee Fork he was pursued and had a narrow escape from a party of Indians, who followed him to the Creek; but finally, he entered the city of Independence, Missouri within less than the time he himself had specified. It is said that upon being assisted from the saddle, it was found to be stained with his blood. The entire ride was made without sleep, and it was the most remarkable instance of human endurance on record. He made the trip once before in 13 days, which was considered wonderful, but on this trial surpassed even his own expectations. Aubry was killed in a saloon fight at Santa Fe in 1854.

One of the prominent hunters and guides along the old Santa Fe Trail in the early days was Colonel A. G. Boone, a grandson of the famous pioneer of Kentucky. He was one of the most accomplished plainsmen in the country, could speak all the Indian languages, and always enjoyed the confidence of the tribes. He could go among them in the midst of a war dance, without fearing the slightest injury, and was very useful from time to time in aiding in the rescue of captives.

Another notable character was John Smith, known as “Uncle John,” an old trapper and guide, who figured a great deal in frontier history. He had a remarkable experience if only the truth were told, but as the old gentleman got along in years, his imagination became more fertile and his tongue looser, and he spent most of his time in drawing long yarns for the benefit of “tender-feet.” He was a perfect guide, and an excellent hunter; he was acquainted with every fort of the west, and, as he used to say, had drunk out of every spring from the mouth of the Yellowstone to the Red River of the South. One of his characteristics, as described in Colonel Inman’s charming stories, was never to eat quail, and thereby hung a story. The old man was on the plains at one time, with some of his companions, and was about to shoot at a buffalo, when a little quail lit on the barrel of his gun and obstructed his sight. He shook it off, but it returned again. Just at that moment, the party was attacked by the Indians, and the fact that he had a load in his gun saved his life. He always believed that the interference of that quail with his buffalo shooting was a special interposition of Providence.

Some of the eyes that cross these pages perhaps have seen an Indian romance of a wild and gory character called “The Wild Huntress of the Plains,” or by a name akin to that, and read the story without suspecting that it was founded upon fact. It is true that there used to be a wild woman roaming over the plains of Kansas, riding the most intractable of mustangs, and carrying danger wherever she went. Her eye was black and wild and glittered like that of a snake, and her long, uncombed hair, which the wind had tangled, floated out behind her as she rode, like a cluster of writhing vipers. She lived in an old dug-out and ate herbs and roots and the meat of buffalo she killed. The Indians feared her, as they had a superstitious terror of all insane persons, and her presence in the neighborhood of one of their villages was a sufficient reason for immediate and hasty removal. She was known as Crazy Ann and was formerly the wife of a railroad contractor by the name of Peters, who was killed in the most brutal manner by the Indians before her very eyes. She became a maniac, and for several years roamed on the prairies unrestrained, but was finally taken to an insane asylum, where she died.

While the railroad was pushing out in the early days, Newton, Kansas was a pretty hard town, and its inhabitants were very different from the pious Mennonites who later lived there. Always, there was one or more mysterious individuals in these frontier pandemoniums, who somehow preserved their secrets and still retained the regard, if not the respect, of the community. The mystery of Newton was an old man, dwarfish in stature, and deformed, who kept a saloon and gambling house. He had a wonderfully intelligent face, quick, shrewd eyes, and had only two apparent objects in life. One was to accumulate money, for he was a perfect miser, and a handyman at all games of cards; and the other a watchful and tender solicitude for the welfare of his daughter, the only being for whom he ever showed any respect or affection. She was a beautiful girl, bright, intelligent, and apparently loved the crooked old miser.” He was educated, and taught her from books, in a building half tent and half shanty, that stood behind his gambling house. She did the cooking and was seldom seen except when he was with her. Every luxury that could be secured on the inhospitable frontier was seized for the girl by the old man, and the only money he was ever known to expend from the large quantities he gathered in, was for her benefit.

The story went that she was his only child and that he had come west to make a fortune, in order that when she grew to womanhood she might live like a lady in the States. Nobody knew where he came from, although he had for several years driven a team and handled some goods of his own on the Santa Fe Trail, nor did anyone know his name. He carried a nickname, as every other man of consequence in the community did, and it was derived from his peculiar habitual expression, “Jes-so.” To every remark that was addressed him, to every assertion that was made in his presence, be it a matter of dinner or death, he had only one reply, and that was: “Jes-so.”

The girl was about 17 and was so carefully guarded that she was discontented and used to have sly flirtations with cowboys and other hangers-on at the camp, which would have ended in murder had the old man discovered them. While he was at the card table, she was chatting at the rear of her tent with one of her many lovers. And one night she eloped!

The old man used to gamble all night and sleep all day, and when he awoke one afternoon from his slumbers, he detected her absence. A cowboy named “Bunny” was also missing, and the old man, by making inquiries, discovered that they had been seen together during the previous evening. He remarked “Jes-so,” as usual, but he crawled through the town like a wild-cat, and borrowing a horse, buckled his revolver belt around him, and started across the prairie toward the ranch where “Bunny” was employed.

The next day he returned to Newton, said “Jes-so,” as usual, but sold out his traps, and disappeared forever.

Two days later, travelers along the road reported that they had found, in an abandoned mud-hut near the river, two corpses, those of a beautiful girl and a stalwart young man. They were on their knees, their right hands were clasped, and a catholic prayerbook, covered with blood, lay on the floor beside them. The old man had discovered the betrayal of his daughter by “Bunny,” had married them, according to the catholic formula, himself, and then shot them both through the heart.

General Custer’s chief scout during the Indian war of 1867 was Will Comstock, one of the most remarkable of the many remarkable men who have filled the atmosphere of the frontier with stories of daring. Custer said of him: “No Indian knew the country more thoroughly than he; perfect in horsemanship; fearless in manner; a splendid hunter; and a gentleman by instinct, as modest and unassuming as he was brave, he was an interesting, as well as a valuable, companion.”

From the sole of his slender foot to the locks of his raven hair, he was a perfect scout and a sleuthhound on an Indian trail. His complexion was very dark, and he was said to be the son of a Delaware Indian woman by a white trapper, but no one ever actually knew his ancestry, or where he came from. He was unpretending and seclusive, but his exploits would fill a volume. Always superstitious, by virtue of his mother’s blood, there seemed to be a cloud hanging over his life which made him avoid the haunts of men and seek his own companionship. He never had a “partner,” as most scouts do, and when he undertook his perilous missions, he always went alone.

He died a victim of the treachery of the Indians. He had been dispatched by General Philip Sheridan to an Indian village to invite the chiefs to a council, and some of them started to return with him. After they had ridden a few miles together, and he was thrown off his guard, an Indian behind him leveled his gun and shot Comstock through the back, killing him instantly. Some of the chiefs who were in the party, months afterward told the circumstances of his death and explained that the treacherous deed was done, not with their consent or expectation, but by this Indian of his own motive, to revenge the death of his father, whom Comstock had killed.

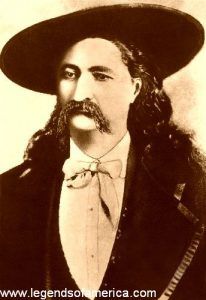

A conspicuous figure upon the plains for many years after the Civil War was the notorious William Hickok, or, as he was more generally known, “Wild Bill.” This individual was at one time not only a famous, but a worthy, character, as worthy as men of his class often are, but dissipation and gambling turned a skillful guide and a brave scout into a worthless desperado. As Ned Buntline, the prolific writer of border romance discovered “Buffalo Bill,” Colonel George Ward Nichols, a gallant soldier, and later the esthetic manager of the Cincinnati College of Music discovered “Wild Bill.” During the war Colonel Nichols was in Missouri, in the army, attached to the headquarters of the commanding officer, and there he first became acquainted with the hero of so many bloody episodes, who was then a very brave, intelligent and valuable Union scout, more dreaded and feared by the rebels than any 40 men in the Union Army. Indeed, most of the early homicides on Bill’s long catalog were the result of attempts to entrap or betray him by the rebel sympathizers of Missouri. and officially, as the sheriff of the town of Abilene. During General Hancock’s campaign in 1867, he was the chief of scouts, and General Custer, in his description of the events of that summer, said of him:

“Hickok went into the army as a private in an Illinois regiment, and his home was in one of the small towns in the interior of the state. His regiment was sent to Missouri, where his remarkable nerve, his desperate recklessness, and general intelligence, soon attracted the attention of the commanding officer, who made use of him as a scout. He was afterward detailed from his company and attached to the headquarters of General Curtis in that capacity. His services are highly commended by his commander, and he performed such feats of daring and had such wonderful escapes as to make him the text of a great many interesting chapters of both history and romance. Colonel Nichols introduced him to the public in a sketch published in a widely circulated magazine near the close of the war, and it gave the scout great fame.”

Bill was a remarkable man in appearance as well as in experience. He was six feet two inches tall, slender, and as straight as an arrow. His face was small for so large a man, his profile regular, and he habitually wore a pleasant expression. Until the close of the war, when he went on the plains, he did not wear long hair, nor beaded buckskin garments, nor did he drink liquor or gamble,—those accomplishments he acquired after he became famous.

After “Wild Bill” went to Kansas, he fell into bad ways. He kept a saloon and a gambling house, and killed many men, both on his private account and officially, as the sheriff of the town of Abilene. during General Hancock’s campaign in 1867, he was the chief of scouts, and General Custer, in his description of the events of that summer, said of him:

“Whether on foot or horseback, he was one of the most perfect types of manhood I ever saw. His influence among frontiersmen was unbounded, and his word was law. Wild Bill is anything but a quarrelsome man, yet no one but himself can enumerate the many conflicts in which he has been engaged, and which have invariably resulted in the death of his adversary. I have personal knowledge of a dozen men he has killed, one of them being a member of my own command. Others have been severely wounded, but he always escaped unhurt. Yet in all the affairs of this kind in which Wild Bill has performed a part, there is not a single instance, in my knowledge, in which the verdict of 12 fair-minded men would not have been pronounced in his favor. That the even tenor of his way continues to be disturbed by little events of this character may be inferred from an item in the press, which states that ‘the funeral of Jim Bludso, who was killed the other day by Wild Bill, took place today.’ It then adds, ‘the funeral expenses were borne by Wild Bill.’ What could be more thoughtful than this? Not only to send a fellow mortal out of the world but to pay the expenses of his transit.”

Wild Bill finally became a refugee from justice, and after “removing” numerous sheriffs, detectives and other officers of the law was shot down like a dog, in Deadwood, several years ago, by a man whom he had tried to murder.

“Buffalo Bill,” before he left the plains for the “dramatic arena,” was also a frontier figure along the Santa Fe Trail, and was originally a protege of “Wild Bill,” serving under him as Deputy Sheriff at Abilene.

By William Eleroy Curtis, A Summer Scamper Along the Old Santa Fe Trail, and Through the Gorges of Colorado to Zion; Inter Ocean Publishing Company, 1883. Compiled & edited by Kathy Alexander, updated February 2020.

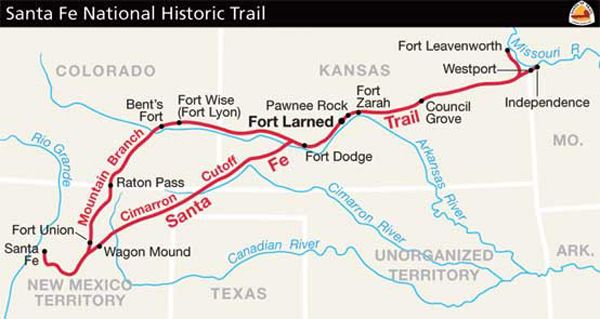

Santa Fe Trail Map

Also See:

Santa Fe Trail – Highway to the Southwest

Early Traders on the Santa Fe Trail