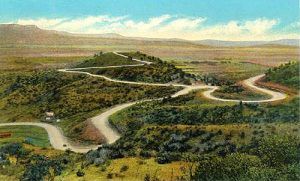

The Raton Pass, through which the Old Trail ran, was a relatively fair mountain road, but originally it was almost impossible for anything in the shape of a wheeled vehicle to get over the narrow rock-ribbed barrier; saddle horses and pack-mules could, however, make the trip without much difficulty. It was the natural highway to southeastern Colorado and northeastern New Mexico. Still, the overland coaches could not get to Trinidad by the shortest route, and as the caravans also desired to make the same line, it occurred to Uncle Dick that he would undertake to hew out a road through the pass, which, barring grades, should be as good as the average turnpike. He could see money in it for him, as he expected to charge a toll, keeping the road in repair at his own expense. He procured from the legislatures of Colorado and New Mexico charters covering the rights and privileges that he demanded for his project.

In the spring of 1866, Uncle Dick took up his abode on the top of the mountains, built his home, and lived there until 1893, when he died at a very ripe old age. The old trapper had imposed on himself anything but an easy task in constructing his toll road. There were great hillsides to cut out, immense ledges of rocks to blast, bridges to build by the dozen, and huge trees to fell, besides long lines of difficult grading to engineer.

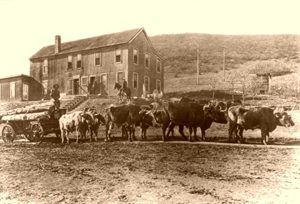

Eventually, Uncle Dick’s road was a fact, but when it was completed, how to make it pay was a question that seriously disturbed his mind. I will quote the method he employed to solve the problem in his own words: “Such a thing as a toll road was unknown in the country at that time. People who had come from the States understood, of course, that the object of building a turnpike was to enable the owner to collect tolls from those who traveled over it. Still, I had to deal with a great many people who seemed to think that they should be as free to travel over my well-graded and bridged roadway as they were to follow an ordinary cow path.

“With the stage company, the military authorities, and the American freighters, I had no trouble. With the Indians, when a band came through now and then, I didn’t care to have any controversy about so small a matter as a few dollars toll! Whenever they came along, the toll gate went up, and any other little thing I could do to hurry them on was done promptly and cheerfully. While the Indians didn’t understand anything about the system of collecting tolls, they seemed to recognize that I had a right to control the road, and they would generally ride up to the gate and ask permission to go through. Once in a while, the chief of a band would think compensation for the privilege of going through in order and would make me a present of a buckskin or something of that sort.

“My Mexican patrons were the hardest to get along with. Paying for the privilege of traveling over any road was something they were totally unused to, and they did not take to it kindly. They were pleased with my road and liked to travel over it until they came to the toll gate. This they seemed to look upon as an obstruction that no man had a right to place in the way of a freeborn native of the mountain region. They appeared to regard the toll gate as a new scheme for holding up travelers for the purpose of robbery, and many of them evidently thought me a kind of freebooter who ought to be suppressed by law.

“Holding these views, when I asked them for a certain amount of money before raising the toll gate, they naturally differed with me very frequently about the propriety of complying with the request.

“In other words, there would be, at such times, probably an honest difference of opinion between the man who kept the toll gate and the man who wanted to get through it. Anyhow, there was a difference, and such differences had to be adjusted. Sometimes I did it through diplomacy, and sometimes I did it with a club. It was always settled one way, however, and that was in accordance with the toll schedule so that I could never have been charged with unjust discrimination of rates.”

Soon after the road was opened, a company composed of Californians and Mexicans, commanded by a Captain Haley, passed Uncle Dick’s toll gate and house, escorting a large caravan of about a hundred and fifty wagons. While they stopped there, a non-commissioned officer of the party was brutally murdered by three soldiers, and Uncle Dick came very near to being a witness to the atrocious deed.

Las Vegas, New Mexico, where the privates had been bound and gagged, by order of the corporal, for creating a disturbance at a fandango the evening before.

“They were taken into custody and made a confession, in which they stated that one of their number had stood at my door on the night of the murder to shoot me if I had ventured out to assist the corporal. Two of the scoundrels were hung afterward at Las Vegas, New Mexico, and the third sent to prison for life.”

The corporal was buried near where the soldiers were encamped at the time of the tragedy. His lonely grave frequently attracts the passengers’ attention on the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad.

In 1866-67 the Indians broke out, infesting all the most prominent points of the Santa Fe Trail and watching an opportunity to rob and murder so that the government freight caravans and the stages had to be escorted by detachments of troops. Fort Larned, Kansas, was the western limit where these escorts joined the outfits going over into New Mexico.

There were other dangers attending the passage of the Trail to travelers by the stage besides the attacks of the Indians. These were the so-called road agents — masked robbers who regarded life as of little worth in accomplishing their nefarious purposes. Particularly were they common after the mines of New Mexico began to be operated by Americans. The bandits’ object was generally the express company’s strongbox, which contained money and other valuables. Of course, they did not hesitate to take what ready cash and jewelry the passengers might happen to have upon their persons, and frequently their hauls amounted to large sums.

When the coaches began to travel over Uncle Dick’s toll-road, his house was made a station, and he had many stage stories. He said:

“Tavern-keepers in those days couldn’t choose their guests, and we entertained them just as they came along. The knights of the road would come by now and then, order a meal, eat it hurriedly, pay for it, and move on to where they had arranged to hold up a stage that night. Sometimes they did not wait for it to get dark, but halted the stage, went through the treasure box in broad daylight, and then ordered the driver to move on in one direction while they went off in another.

“One of the most daring and successful stage robberies that I remember was perpetrated by two men when the eastbound coach was coming up on the south side of the Raton Mountains one day about ten o’clock in the forenoon.

“On the morning of the same day, a little after sunrise, two rather genteel-looking fellows, mounted on fine horses, rode up to my house and ordered breakfast. Being informed that breakfast would be ready in a few minutes, they dismounted, hitched their horses near the door, and came into the house.

“I knew then, just as well as I do now, they were robbers, but I had no warrant for their arrest, and I should have hesitated about serving it if I had because they looked like very unpleasant men to transact that kind of business with.

“Each of them had four pistols sticking in his belt and a repeating rifle strapped onto his saddle. When they dismounted, they left their rifles with the horses but walked into the house and sat down at the table, without laying aside the arsenal they carried in their belts.

“They had little to say while eating but were courteous in their behavior and very polite to the waiters. When they had finished breakfast, they paid their bills and rode leisurely up the mountain.

“It did not occur to me that they would take chances on stopping the stage in daylight, or I should have sent someone to meet the incoming coach, which I knew would be along shortly, to warn the driver and passengers to be on the lookout for robbers.

“It turned out, however, that a daylight robbery was just what they had in mind, and they made a success of it.

“About halfway down the New Mexico side of the mountain, where the canon is very narrow and was then heavily wooded on either side, the robbers stopped and waited for the coach. It came lumbering along by and by, neither the driver nor the passengers dreaming of a hold-up.

“The first intimation they had of such a thing was when they saw two men step into the road, one on each side of the stagey each of them holding two cocked revolvers, one of which was brought to bear on the passengers and the other on the driver, who was politely but very positively told that they must throw up their hands without any unnecessary delay, and the stage came to a standstill.

“There were four passengers in the coach, all men, but their hands went up at the same instant that the driver dropped his reins and struck an attitude that suited the robbers.

“Then, while one of the men stood guard, the other stepped up to the stage and ordered the treasure box thrown off. This demand was complied with, and the box was broken and rifled of its contents, which fortunately were not of very great value.

“The passengers were compelled to hand out their watches and other jewelry, as well as what money they had in their pockets, and then the driver was directed to move up the road. In a minute after this, the robbers had disappeared with their booty, and that was the last seen of them by that particular coach-load of passengers.

“The men who planned and executed that robbery were two cool, level-headed, and daring scoundrels, known as ‘Chuckle-luck’ and ‘Magpie.’ They were killed soon after this occurrence, by a member of their own band, whose name was Seward. A thousand dollars had been offered for their capture, which tempted Seward to kill them one night when they were asleep in camp.

“He then secured a wagon, into which he loaded the dead robbers, and hauled them to Cimarron City, where he turned them over to the authorities and received his reward.”

Among the Arapaho, Wooten was called “Cut Hand” because he had accidentally lost two fingers on his left hand in his childhood. The tribe had the utmost veneration for the old trapper, and he was perfectly safe at any time in their villages or camps; it had been the request of a dying chief, who was once greatly favored by Wootton, that his warriors should never injure him although the nation might be at war with all the rest of the whites in the world.

Uncle Dick died a few seasons ago at the age of nearly eighty. He was blind for some time, but a surgical operation partly restored his sight, which made the old man happy because he could look again upon the beautiful scenery surrounding his mountain home, really the grandest in the entire Raton Range. The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad had one of its freight locomotives named “Uncle Dick,” in honor of the veteran mountaineer, past whose house it hauled the heavy-laden trains up the steep grade crossing into the valley beyond. At the time of its baptism, now fifteen or sixteen years ago, it was the world’s largest freight engine.