As an honorable man, Samuel Mason served as a militia captain in the American Revolution. Later, however, he would turn pirate on the Ohio and the Mississippi Rivers and lead highwaymen along the Natchez Trace.

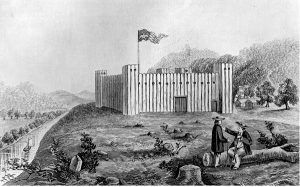

Samuel Mason was born in Norfolk, Virginia, to a distinguished family on November 8, 1739, and raised in Charles Town, West Virginia. He married Rosanna Dorsey in about 1767, and the couple would eventually have eight children. In 1773, he moved his family to Ohio County, West Virginia. During the American Revolution, he became a captain of the Ohio County Militia, Virginia State Forces in January 1777. He was given command of Fort Henry on the Ohio frontier in present-day West Virginia.

In the summer of 1777, while colonial soldiers to the east were fighting the war for independence, Mason feared attacks by the Indian allies of the British. On August 31, 1777, he was proven correct when a band of Native Americans from several eastern tribes attacked the fort.

Initially, the Indians fired on several men outside the fort, rounding up horses. When Mason heard the shots, he gathered 14 men and rode to their rescue. However, this was precisely what the warriors had hoped for, and they quickly ambushed the rescue party, killing every last man except Captain Samuel Mason. The captain, however, was severely wounded and escaped death by hiding behind a log. He was soon rescued and recovered from his wounds to command Fort Henry for two more years.

In 1779, he moved to Washington County, Pennsylvania, to buy a 500-acre farm. In July 1781, he was elected justice of the peace and was named an associate judge just a few months later. In 1782, Mason appeared successful, paying taxes on his 500-acre farm and two horses, four cows, and six sheep. He also owned four slaves. However, Mason was struggling financially and had become deeply indebted. After being repeatedly accused of being a thief, he went to Kentucky in 1784. His Pennsylvania farm was sold at a sheriff’s sale to pay part of his debt the following year. In 1789, the Pennsylvania court sent a man to Kentucky to collect the remaining debt but was unsuccessful.

By the early 1790s, Mason settled at Red Banks, now Henderson, Kentucky. Later, he moved downriver to Diamond Island, where he began to engage in criminal activity. By 1797, he moved his headquarters further downriver to Cave-in-Rock on the Illinois shore. By this time, he had gathered several followers who openly based themselves at Cave-in-Rock. Here, Mason and his men warmly welcome riverboat travelers to rest and eat. However, while these visitors enjoyed the hospitality, Mason’s men checked their supplies and goods for anything of value. If they found something, they would wait until the next day and, when the visitors continued, rob them as they made their way around the river’s bend.

While at Cave-in-Rock, Mason and his men briefly harbored the notorious Harpe brothers, who were on the run from the law. The Harpes were a couple of the most brutal outlaws at the time and distinguished themselves as America’s first serial killers. Though the Mason Gang could be ruthless, even they were appalled at the actions of the Harpes. After the murderous pair began to take travelers to the top of the bluff, stripping them naked and throwing them off, they were asked to leave.

In the summer of 1799, the Mason Gang was forced to leave Cave-in-Rock when they were attacked by a group called the “Exterminators.” Captain Young of Mercer County, Kentucky, led this group of vigilante bounty hunters. Mason then moved his operations downriver, settled his family in Spanish Louisiana, and became a highwayman on the Natchez Trace in Mississippi, robbing and killing unsuspecting travelers.

In April 1802, Mississippi Governor William C. C. Claiborne was informed that Samuel Mason and Wiley Harpe had attempted to board the boat of Colonel Joshua Baker between Yazoo and Walnut Hills, now Vicksburg, Mississippi. The governor responded by ordering Colonel Daniel Burnet, with 15-20 volunteers, to track down Mason and his men. A reward of $2,000 was offered for their capture.

Though dozens of men searched for the Mason Gang, the outlaws continued their evil deeds along the Natchez Trace, striking one caravan with horrific brutality. Another posse of residents and a few bounty hunters was raised to go after them. The posse quickly pursued, learning that Mason and his men hid less than a mile west of the Trace near Rocky Springs, Mississippi. When they came upon the camp, they found it had been hastily abandoned. Though the outlaws’ trail was fresh, most posse chose not to follow instead of remaining at the camp, searching for any hidden loot the outlaws may have left. However, a few men continued the pursuit but abandoned the search when they lost the trail.

Months later, Spanish officials were more successful. In January 1803, they arrested Mason, four of his sons, and several other men at the Little Prairie settlement, now Caruthersville, in southeastern Missouri. Mason and his family were taken to the colonial government in New Madrid, Missouri, where a three-day hearing was held to determine whether Mason was a pirate. Although Mason claimed he was simply a farmer his enemies had maligned, the presence of $7,000 in currency and 20 human scalps in his baggage convinced the Spanish he was guilty. Mason, his family, and the other men boarded a boat to New Orleans, Louisiana. They would be handed over to the American governor in the Mississippi Territory. However, while being transported, Mason and Wiley Harpe, who were using the alias of John Sutton, overpowered their guards and fled. Though Mason was shot in the leg, he made good his escape.

Governor William C. C. Claiborne immediately added an additional $500 reward for their recapture, making the total reward $2500. This staggering amount prompted Wiley Harpe and another man to bring Mason’s head in an attempt to claim the reward in September 1803. Whether they killed Mason or he died from his leg wound is unknown. However, the two pirates were recognized, arrested, tried in federal court, and found guilty of piracy rather than collecting a reward. They were hanged in Greenville, Mississippi, in early 1804.

It was never recovered from the thousands of dollars of cash and other valuables the Samuel Mason Gang stole over the years, prompting several lost treasure tales. Some of this treasure is said to have been hidden at Cave-in-Rock, Illinois, where the Mason Gang made their headquarters for several years. This large cave, worn into the limestone bluffs of the Ohio River, has been used for thousands of years by the Native Americans. However, it is better known for the many outlaws it harbored. In addition to the Mason Gang, it also served as the hideout of the vicious Harpe brothers, highwaymen James Ford and Isaiah Potts, several counterfeiters, the post-Civil War bandit Logan Belt, and many others.

In this 55-foot wide cave, which leads a short distance into the bluff, it is said that over $1 million worth of stolen loot, gold, cash, and counterfeit bills changed hands between 1790 and 1830 alone. In 1800, the Mason Gang was rumored to have hidden a large stash of gold here, but Mason was killed before retrieving it. In addition to the gold allegedly hidden by Mason, more caches of gold and silver are said to be hidden along the cliff face. The notorious Cave-in-Rock is also said to be haunted if the hidden treasure isn’t enough of a legend. But, that’s a whole ‘nuther story.

Cave-in-Rock is now a state park located in Hardin County, Illinois.

Today, all that’s left of Rocky Springs, besides the church and cemetery, are a couple of old safes and a cistern.

Another legend of Mason’s cache is said to be hidden somewhere in the Rocky Springs, Mississippi, area where Samuel Mason and Wiley Harpe once had a hideout in the early 1800s. After having made a large robbery on the Trace, they returned to their campsite. Though they often carried their stolen loot on a couple of mules’ backs, they knew they were being aggressively pursued. This time, they decided to bury their cache near their camp to be retrieved later. However, neither Samuel Mason nor Wiley Harpe would be able to do so, as they would be dead. According to the legend, there is said to be some $75,000 in stolen gold and silver coins buried somewhere between the old church and cemetery at Little Sand Creek. However, looking for it today would be a bad idea, as it is privately owned or belongs to the National Park Service.

Another tale says that Samuel Mason buried a very large chest – some seven feet long about four miles northwest of Roxie, Mississippi. The chest, filled with stolen valuables, including gold coins and jewelry, was allegedly buried near an artesian well on the Reber Dove Farm. If the story is true, the cache has never been found.

Yet, more tales say that Mason loot was hidden at Stack Island, Mississippi; the ghost town of Tillman, Mississippi, in Claiborne County; and as much as $250,000 somewhere near one of the gang’s favorite drinking spots – the Colbert Tavern and Inn on the Natchez Trace near Bissell, Mississippi.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2023.