By Charles Dawson in 1912

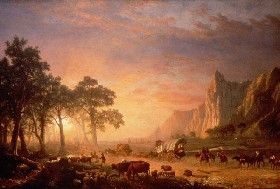

Albert Bierstadt’s Oregon Trail, 1869

Told by an old settler in Jefferson County, Nebraska

In the late 1860s, my wife and I, with our bunch of towheaded youngsters, were headed westward, traveling by ox-team in a canvas-topped wagon bound for Nebraska in response to the solicitations of my father. He had settled there a few years previously. Crossing the Missouri River in the early days of spring at St. Joseph, Missouri, we joined one of the first caravans of emigrants going westward over the Old Oregon Trail. Traveling over the wonderful prairies and through the rich valleys of eastern Kansas, we had our ideas of the Great American Desert rudely but pleasantly shattered. In due time, we reached our destination and encamped on the tract of land selected for us, which was a well-timbered and watered body of land, lying along a spring-fed stream that ran back into a valley which was flanked by bluffs capped by ledges of sandstone.

As the first tints of green began to appear in the landscape, it was a wonderful sight to witness the unfolding of such picturesque scenery, the likes of which we had never seen before.

Our new home lay about halfway between the Old Oregon Trail and the Little Blue River, but this is all I will tell you, for ghosts and their haunts should not be too definitely located, as it might spoil their charms or veracity if there be any.

We immediately commenced building a home and, with the aid of my relatives and neighbors, contrived to erect a habitable log cabin, a one-room affair with a loft above, a clapboard roof, and mud-and-stick chimney, and a stone fireplace at one end.

Compared with our previous places of habitation and modes of living, this seemed, at first, to be very primitive and almost unendurable. Still, before long, we grew to regard this homely little log cabin as the coziest place it had been our pleasure to reside in.

With the coming of the warm days of spring, we broke out the little flats of land along the creek bottom and planted them with corn, potatoes, melons, etc. Gardens were made, and we entered into the cultivation of our promising crops, hoping to reap an abundance of our needs. Nature had by now fully clothed the whole panorama with a beautiful profusion of foliage, blossom, and color. Our little world seemed to be filled to overflowing with promise and happiness. Strawberry-time had come. The hillsides were covered with the patches of this luscious red fruit. One Sunday morning, my wife and I, light of heart, arm in arm, set out to roam the hillsides to gather a pail full of strawberries. We were soon amid a profusion of strawberries, so plentiful, full and ripe on all sides of us, that we ran here and there, trampling underfoot many berries, in our greed to secure the nicest ones.

Our pail was soon full to the brim, and our fingers and lips stained from picking and eating until we were so full, we had to stop. Then, feeling the tire of contented satisfaction, we sat down upon a convenient rock, lazily viewing the surrounding scenery, resting before we would attempt our home-bound journey. With half-closed eyes lying back on the big shaded ledge of stone, my thoughts were dwelling on the incidents of the short past, in which we had left the comforts of civilization and had taken up our abode in this the land of promise, thinking how content we were. Just as I began to conjecture the future, I was aroused by an exclamation by my wife, who was now pointing across the rock-walled ravine to a springy spot, shaded by scattered clumps of underbrush. Brushing aside the sleepy tangles of my eyes, I noted the cause of her excitement, which I first thought might be Indians. Underneath and in the tangles of leaf and stem, quite in contrast to the rich background of green, were berries — strawberries of great size and blood-red color, rivaling even the choicest of the same ones we had seen in the gardens of our Eastern homes.

Leaving our already filled pail, we hastened over to view the wonderful sight. Picking and eating the first few that we came to, we decided to take some home in my old hat and the wife’s apron; so, with many noises of wonder and surprise, we filled these articles. As I strode through a thick tangle of brush in leaving the patch, my foot caught on an object which threw me to the ground, and on turning over, I found at my feet the skull of a human being. Leaping up, I rushed out of the thicket, almost completely unnerved at my ghastly find. My wife, who had witnessed my stumble and quick leap up, ran back towards me, inquiring with alarm, the cause of these unusual actions. Together we walked back, and I pointed to the eyeless bare skull that was apparently grinning at us from his moldy moss-covered retreat from which my foot had ruthlessly torn him but a moment before.

Nebraska homestead

Proceeding into the thicket to investigate more fully, we found that underneath the leafy and molding foliages of the past seasons which had covered their bodies were the bones of many other persons. In fact, our strawberry patch had been the burial ground of the unknown dead. My wife and I, stilled by the presence of the dead, stood with bowed heads and silently offered up prayers to Him on high, who alone could give the solution of this mystery.

Glancing up, I met the gaze of my wife and overturned my old hat was overturned as the corners of her apron were dropped and the berries spilled on the ground, for we both knew without further questioning what had caused the berries to be so big and red.

Then, we did a thorough search thereabout for the bones of the unknown dead, faithfully gathering the bones as they lay, endeavoring to give each skull its own and a full complement of bones. Finally, we felt that this duty had been performed, and the result was twelve skeletons, which we judged were a party of emigrants of men, women, and children.

After considerable labor, a grave was dug, the bones placed within, and filled with earth and stones covering the top to mark and protect the grave. Thoroughly tired by our toil, we wended our way homeward, conscious that we had fulfilled our duty to those poor unfortunate beings by giving them at least a burial. After supper, we gathered on the doorstep in the twilight of the evening, feeling content and at peace, when there came an uncanny, weird moan or cry, like that of woman or child in the depth of anguish or despair. Listening in awe, I awaited the repetition of that mournful sound. Soon it came, now in the fringe of trees about the cabin, then in the waist-high corn. Swiftly recalling the incidents of the day, I tried to assure myself that it was not real, that this was but the result of a befuddled mind, just imagination; but the children were now questioning us as to the cry, and upon receiving non-committal answers, and perhaps reading our faces, they grew frightened and began to cry.

Ghost

To assert myself and to allay their fears, I arose and said to my wife, “Hand me my rifle, and I will go down there and shoot that old owl, tree-toad, or whatever it may be.” Leaving my wife and children on the porch, I proceeded to search about in the growing corn, around the barn, and all through the nearby underbrush, but without result, although I seemed to be following the voice from point to point. Finally, it seemed to be at the cabin. Hastening there, I found that my family had fled within and had barred the door. Undaunted, I continued the search, following the clues from where I heard the voice. After vain attempts which led me to the roof, around and underneath the cabin, I too was frightened and went into the cabin. There was not much sleep for us that night, for we could hear the cries of our unearthly visitor at frequent intervals until the early dawn of the morning. Night after night, we had much the same experience until we grew accustomed to it and were but little disturbed. Our neighbors joined us on several occasions to find the mysterious visitor. Still, despite the most exacting vigils and search, we gave it up, for not one single object or reason could be found that might be suspected of making the nightly occurring sounds, which the neighbors dubbed “The Lost Woman Ghost.”

The summer wore on, succeeded by the bountiful autumn harvests. We should have been happy and content, but the “nightly visitor” had worn on our nerves, so after the harvest had been gathered, I was only too glad to sanction the wife’s suggestion that we go and live with my father down on the Little Blue River, for the winter, as it was too lonesome away up here by ourselves.

We spent the long winter down there, hunting and trapping, occasionally returning to see if everything was all right at our homestead, but never staying overnight, so we did not know if our unwelcome guest had departed or not. With the opening days of spring, we moved back, for our crops needed to be planted and tended, and the first night of our return was celebrated by the usual performance of the unseen voice.

Of course, this was annoying but, what could we do? Then there was no harm resulting, so we settled down, accepting the situation as best we could. Strawberry time came again, and we started to search the hillsides and ravines for the big red berries. Our wanderings brought us to the burial-place of the unknown party of people that we had found a year ago. Here, we stood for a moment with bared heads in reverence, swiftly recalling the incidents of their past as we knew of them, praying that we might in some way learn who they were so that their relatives might know of their fate. As we realized the improbability, we turned away with dimmed eyes and continued to ascend the hill.

Upon reaching the top, we sat down upon a large flat boulder to rest. The whole panorama lay spread out at our feet, and across the ravine to our right was a hillside almost mountainous in appearance, cut and broken by irregular, rock-filled canyons or gorges, down which, trickling spring-fed streams flowed. The rock-strewn hillside was covered with straggling growths of dwarfed oaks and hackberry trees, with the hill itself rising high to the blue skyline, capped with a heavy ledge of brown sandstone, which was cracked and fissured deeply with dark recesses and many overhanging shelves, which suggested ideal retreats for wild animal life. As we searched with our eyes, every part of its face for some new wonder of formation, a ghastly sight came to our vision – the skeleton of a human being. On closer investigation, we found it to be that of a woman, huddled in a crouched, squatting position, back against the wall of a cavern-like place, seemingly as though she had taken refuge here, only to be found, and had raised her arms to ward off the blow that had stilled her life. Tenderly, we gathered up the bones, carried them down to the burial place, and interred them with the rest, which we judged to have been her companions. The afternoon was spent in the search for others that might be lying unburied on the hillsides, but the search proved fruitless; our only other find being a few piles of fire-warped wagon-irons and charred woodwork, near which lay bones of oxen, many having the wooden yokes still around their necks. A few arrows were found scattered about in these piles of bones, so we knew that this was the work of Indians.

In the twilight of that evening, I sat upon the broad doorstep of our cabin, thinking of all these things, the part that we had played and who these people might have been; then came the thought, could there be any connection between them and the ghostly visitor? If so, perhaps it would give me an answer tonight. Though I waited and meditated long into the night, I was in one way disappointed, for the voice did not come that night and never again afterward. So, to me, the mystery has deepened as the years have gone by. Was this the spirit of the murdered woman beseeching me to bury her bones beside those we had previously buried, who no doubt had met a similar fate? I hope so, and if this gave rest to the Soul, let it be the end.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

Charles Dawson, author

About the Author: This article was excerpted from Charles Dawson’s book, Pioneer Tales from the Oregon Trail and Jefferson County, published in 1912. Dawson lived in Jefferson County, Nebraska, for more than 40 years and personally knew many of the pioneers who traveled along the Oregon Trail.

Note: The article, as it appears here, is far from verbatim as it has been edited for clarity, truncated, and updated for the modern reader.