By Randall Parrish in 1907

An interesting phenomenon of Plains settlement, perhaps without parallel elsewhere, were those strange towns which sprang up in a night wherever the advancing railway paused, and which passed away as suddenly with the further extension of the rails, leaving scarcely a trace behind. The peculiarity of the conditions under which these earliest overland roads were constructed made such mushroom towns inevitable, and the nature of their population served to render them sufficiently picturesque. Stretching boldly forth into an uninhabited and barren waste, to which every pound of material required and every man employed had to be transported, the end of the track, both on the Union Pacific and the Kansas Pacific Railroads, became of necessity a great temporary distributing point, full of unceasing activity and feverish, throbbing life. Money was plentiful, and no restraints of home kept the restless inhabitants within bounds. Gamblers, saloon-keepers, and dissolute women eagerly flocked to each temporary terminus, certain of reaping a quick harvest.

Shacks and tents, rude structures of board, or even sod, sprang up like magic on the bare prairie, and scarcely had the decree gone forth that here the railroad would pause for a while, ere the spot teemed with humanity, a new “city” appeared in the twinkling of an eye. Few of such cities survived; scarcely half a dozen of them yet remain. They all flourished a month, some of them six, reveling in sin and lawlessness, only to pass away utterly from the face of the earth.

Historians have never considered this chapter of frontier life worthy of their pens, yet it deserves picturing as illustrative of how civilization first penetrated the wilds. A writer in Harper’s Magazine, who had been connected with the building of the Kansas Pacific Railroad, embodied his remembrance of those days in an article from which I extract much material.

Ours the task to rescue from oblivion towns which were, but are not. Coyote, Kansas was such a town, the temporary terminus of the railroad in 1868. Nothing could be more dreary than its environment. On every side, the monotonous rolling Plains meeting the cloudless sky. The town itself was a crazy street of shanties; its inhabitants a mob of uncouth men flung down among the buffalo. Where they originally came from was a problem, but the majority had drifted into Coyote from some other mushroom town a hundred miles to the east. They brought with them their dwellings, their stores, the few necessaries of life. The new home was made in a day and was old in a night. Canvas saloons, sheet-iron hotels, sod dwellings, discarded tin cans, and scattered playing-cards littered the ground. The cards were apparently numberless and always in evidence. Says the writer in Harper’s Magazine:

“Before the breath of the north wind, they would rise into the air, the queens dancing like so many witches in effigy, as close over the smooth surface they fled south. A few moments and the barren earth would be swept clean, while the pasteboards, accompanied by stray newspapers and old hats, were fluttering, like a flight of white birds, out of sight. Three days, the usual life of a full-grown prairie gale might pass, and then, as the north wind met the forces of the south, the tenantless air became alive again.

Far off on the heel of the vanquished and the crest of the victor wind, came the white-winged coveys of cards, like the curses of the proverb, on their way home to roost. At nightfall, they had collected beside the track and among the houses and were again as thick as leaves in autumn. Had it been possible for conscience to prick through a Coyote gambler’s skin, how it might have gratified him to see the marked Jack that had fleeced the last stranger rise up like a grasshopper and fly south, beyond the possibility of becoming State’s evidence! And how annoying to wake up and find the knave again under his window!”

Coyote, Kansas lived its brief, eventful life in the midst of the buffalo country. For a hundred miles in any direction, carcasses disfigured the land. The meat, cut into strips or lying on sleds, “jerked” and merchantable, was everywhere. It could be had almost for a song. Occasionally a wild herd, stampeded by careless hunters, would dash directly through the town, bowling over tents in their terror and creating pandemonium among the surprised occupants. To many of the citizens, such an occurrence was only second in interest to a dogfight, and-bets were quite in form. The sporting proclivities of the place were especially aroused on one occasion when a veteran buffalo bull tried in vain to fish out a frightened citizen from behind a log, where he had hurriedly taken refuge after a poor shot at the beast. Try as he would, the infuriated animal could only succeed in ripping the fellow’s pants into rags, but with every thrust, there came a yell which would have done credit to an Apache. Instead of interfering in the fun, the manhood of Coyote placed bets on the result, cheering in turn for the bull or Sandy, with strict impartiality.

Coyote had a brief but merry life. The terminus moved forward to Sheridan, Kansas. The change was easily accomplished. In less than a week, not a shack remained, only thousands of oyster and fruit cans marking the deserted spot. Sheridan, where the terminus remained longer, became a larger Coyote. It was named after the famous General, then stationed at Fort Hays not far distant, and when that hero was finally introduced to his lusty namesake, he is said to have remarked that, as a seat of war, it strongly resembled the Shenandoah Valley, while the yelling and firing of the Irish mob of employees on pay-day reminded him of Stonewall Jackson’s ragged battalions. Sheridan graced the side of a desolate ravine, with the yet more desolate Plains on every side. It was built completed in a month, but before the single street had even been surveyed, the necessity arose for a graveyard, and one was promptly located on a ridge overlooking the town. When any angry citizen threatened to give another a “high lot,” he meant six feet of soil on that hillside. During the first week, three moved in “with their boots on,” and during the winter, the list was swelled to twenty-six.

Odd characters were attracted to such a community as this, as flies to a sugar barrel. The correspondent of Harper’s Magazine thus pictures two who deserve to be embalmed in history: “There was ‘Neb, the devil’s own.’ Neb was an abbreviation of Nebuchadnezzar, which title he won from taking so naturally to grass, or, more correctly, to the prairie, when it was necessary to hide on account of misdeeds. Had anyone been interested enough to make weekly inquiries about Neb’s whereabouts, the answer would generally have been, ‘Out at grass.’ On two occasions, he assisted men to eternity without previously using a boot-jack. Once, when an Irish mob was celebrating pay-day, Neb ran out of a hotel opposite and emptied sixteen shots from a Henry rifle among them. No one was killed, but the ‘devil’s own” found it necessary to go into exile on the back of a stray mule, followed for hundreds of yards by a howling mob and shower of bullets.” Neb ended his glorious career finally at the hands of vigilantes.

Another individual of prominence in Sheridan was “Ascension Stephen.” According to our reporter, —

“This worthy was a half-witted Millerite, who climbed the two buttes once or twice every month, with a saloon tablecloth in his pocket that might answer for wrapper when the trumpet should sound. Fine evenings were often spent by him in this weary and lonely waiting, and on one occasion, he frightened the wits out of some drunken Irishmen by rushing down the hill toward them as they were returning from a wild debauch. So well did the tablecloth do duty on this occasion that, for the first time in months, the Irishmen reached their homes sober. A more effective temperance banner never fluttered in the breeze.”

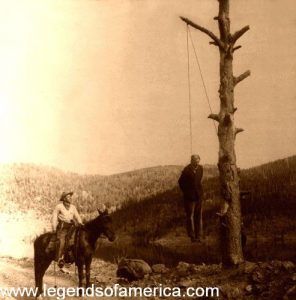

Judge Lynch was well known in Sheridan, and the railroad trestle was a most convenient gallows tree. It was sure to bear monthly and sometimes daily fruit. On more than one occasion, passengers on the cars have drawn back in affright as they beheld staring up at them the face of some Texas Jack, or California Joe who had perished in his sins. Not that Sheridan was, either outwardly or inwardly, moral or law-abiding, but it was generally recognized that there was a limit not to be passed without physical protest. As a rule, morals were rather looked upon as articles of commerce. No one endeavored to possess any unless money was to be made in that way. If any citizen abjured cards, women, and wine, he was pretty certain to have some other game underway which would cost his confiding fellows heavily. But it would be well for him to be far out on the prairie before his victims awoke to the result.

Vengeance was quick and sure, and vigilance juries brought in some queer verdicts in Judge Lynch’s Sheridan court. The chronicler gives one instance where a man, arrested on suspicion, but without evidence, enough against him to convict was indiscreet enough to call the court names. He promptly incurred the following unique sentence: “This yere court feels herself insulted without due cause, and orders the prisoner strung up for contempt.” And strung up he was.

The town fairly blossomed with ” bad men,” and the crop of ” Bill ” heroes was without apparent end. To be named by doting parents William was to assure any ambitious frontiersman future fame: he became Wild Bill, Apache Bill, or some other Bill by some magic in the atmosphere, a terror to tenderfeet, and generally a blasphemous, swaggering bully and coward. Our friend in Harper’s Magazine thus pictures one such he knew in Sheridan. He was a teamster, named William Hobbs.

“He could not have placed a bullet from his carbine in a barn door at a hundred paces. And yet, without any provocation whatever, he seized upon the word California and wore it, although that wonderful State had never, to my certain knowledge, been favored by his presence. This man had not been cut out for a hero. His becoming one was in direct violation of nature’s laws. He was fat, short of wind, red-faced, and timid as a hare. As the frontiersman expressed it, having never lost any Indians, he could not be induced by any consideration to find one. However, by lying in wait for tourists and correspondents, he often managed to get business as a guide. He had donned a suit of buckskins made in St. Louis and would state to the gaping stranger, ‘My name ‘s California Bill yere; over thar it ‘s ‘Pache, on account o’ my fightin’ the tribe.’ He could not have told one of the latter from a Digger, yet soon the Eastern papers came back with thrilling descriptions of this noted scout and Indian-slayer. But I have known this dead shot, to miss, four times in succession, a bison at fifty yards; and one occasion, having mistaken a Mexican herder for an Indian, he fled so fast and far that he lost hat and pistol, and ruined his horse.”

But do not let this incline you to believe there were not real “bad men” in Sheridan. The genuine article was there, and woe to the tenderfoot who thought otherwise.

Gunfight

Both Cody and Hickok, the real Buffalo Bill and Wild Bill, walked those streets, cool, quiet fellows enough, but not the kind of men to play with unless you wanted to die. And there was another kind as well, the typical frontier desperado, always in liquor and always quarrelsome. Tragedy was in the air, yet it scarcely affected the orderly citizen who was content to attend strictly to his own business. The roughs usually fought it out among themselves. Writes this observer justly:

“In all my residence upon the frontier, during which time sixty-two graves were filled by violence, in no case was the murder otherwise than a benefit to society. The dangerous class killed within its own circle but never courted justice by shedding better blood. Orderly people looked on with something like satisfaction, as at wolves rending each other. The snarl was the click of a revolver, and the bite followed the bark. These were the men who gloried in snuffing out a candle, or a life, at thirty paces.”

An illustration occurred in the ending of two notorious bullies of Sheridan, known locally as Gunshot Frank and Sour Bill. From some cause unknown, these worthies quarreled and decided to fight it out in spectacular fashion, to the delight of the crowd. Each armed himself with a revolver, shouldered a spade and started off for the ridge.

The plan was for each man to dig a grave for the other, then exchange places, and see which would have to be filled. However, before the work was half done, “Gunshot” made an impudent remark, and Bill promptly plugged him through the abdomen. Balked of a good part of their anticipated enjoyment, the crowd fell upon ” Sour,” and one of them caved in his head with a spade. That night two men slept in the graves dug by their own hands.

Oh, those were great towns, gone forever from the face of the earth, yet lingering in memory! Who, that ever sought sleep in Sheridan’s one hotel, could ever forget the experiment? Hastily constructed, so as to be moved at a moment’s notice, every creak of a bed echoed from wall to wall. The partitions failed to reach the ceilings by a foot or two, and the slightest sound aroused the whole floor. A pistol shot in No. 47 was quite likely to disturb the peaceful slumbers of the occupant of No. 15, and every ” damn ” in the thronged bar-room below caused the lodger to curl up in expectation of a stray bullet coming toward him through the floor. Under the window, a mob howled, and a man in some distant apartment was struggling vainly to draw off his tight boot, skipping about on one foot amid much profanity. That the boot conquered was evident when the fellow crawled into the creaking bed. ” If the landlord wants them boots off, let him come an’ pull ’em.” You could lie there and hear everything that occurred. Every creak and stamp and snore was faithfully reported. Inside was hell; outside was Sheridan.

But it has all passed away; it was a part of the life that was but is no more forever. The “Bills” have gone the way of all flesh, and so has Sheridan. The train pauses an instant even now at the station bearing the name, but there is nothing visible except the solitary house of the railroad section hands. The hotel, the saloons, the shacks have all disappeared, and about stretch the dull, dead Plains. Only up there on the hill, still in their boots, lie those whom the migrating Sheridan left behind in memory of those days that were.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated December 2020.

About the Author: Mushroom Towns of the American West was written by Randall Parrish as a chapter of his book, The Great Plains: The Romance of Western American Exploration, Warfare, and Settlement, 1527-1870; published by A.C. McClurg & Co. in Chicago, 1907. Parrish also wrote several other books, including When Wilderness Was King, My Lady of the North, Historic Illinois, and others.

Also See other tales by Randall Parrish:

Adventures and Tragedies on the Overland Trail

Beginning of Settlement in the American West

Border Towns of the American West

The Reign Of The Prairie Schooner

Struggle For Possession of the West – The First Emigrants