By Emerson Hough in 1918

We may never know how much history remains forever unwritten. Of the beginnings of the Idaho camps, there have trickled back into the record only brief, inconsequent, and partial stories. The miners who surged this way and that all through the Sierras, the upper Cascades, north into the Selkirks, and then back again into the Rocky Mountains were a turbulent mob. Following the earlier trails of the traders and trappers, having overrun all our mountain ranges, they now recoiled upon themselves. They rolled eastward to meet the advancing civilization of the westbound rails, caring nothing for history and less for the civilized society in which they formerly lived. This story of bedlam broken loose, of men gone crazed, by the sudden subversion of all known values and all standards of life, was at first something which had no historian and can be recorded only by way of hearsay stories which do not always tally as to the truth.

The mad treasure-hunters of the California mines, restless, insubordinate, incapable of restraint, possessed of the belief that there might be gold elsewhere than in California, and having heard reports of strikes to the north, went hurrying out into the mountains of Oregon and Washington, in a wild stampede, all eager again to engage in the glorious gamble whereby one lucky stroke of the pick a man might be set free of the old limitations of human existence.

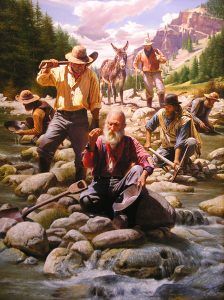

Gold Seekers by Alfredo Rodriquez.

So the flood of gold-seekers — passing north into the Fraser River country, south again into Oregon and Washington, and across the great desert plains into Nevada and Idaho — made new centers of lurid activity, such as Oro Fino, Florence, and Carson. Then it was that Walla Walla and Lewiston, outfitting points on the western side of the range, found a place upon the maps of the land, such as they were.

Before these adventurers, now eastbound and no longer facing west, there arose the vast and formidable mountain ranges which in their time had daunted even the calm minds of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. But the prospectors and the pack-trains alike penetrated the Salmon River Range. Oro Fino, in Idaho, was old in 1861. The next great strikes were to be made around Florence. Here, the indomitable packer from the West, conquering unheard-of difficulties, brought in whiskey, women, pianos, food, and mining tools. Naturally, all these commanded fabulous prices. The price for each and all lay underfoot. Man, grown superman could overleap time itself with a stroke of the pick! What wonder, delirium reigned!

These events became known in the Mississippi Valley and farther eastward. Now, hurrying out from the older regions came many more hundreds and thousands eager to reach a land not so far as California but reputed to be quite as rich. As the bull trains came in from the East, from the head of navigation on the Missouri River, it was then that the western outfitting points of Walla Walla and Lewiston lost their importance.

Southward of the Idaho camps, the same sort of story was repeating itself. Nevada had drawn to herself a portion of the wild men of the stampedes. Carson for its day (1859-60) was a capital not unlike the others. Some of its men had come down from the upper fields, some had arrived from the East over the old Santa Fe Trail, and yet others had drifted in from California.

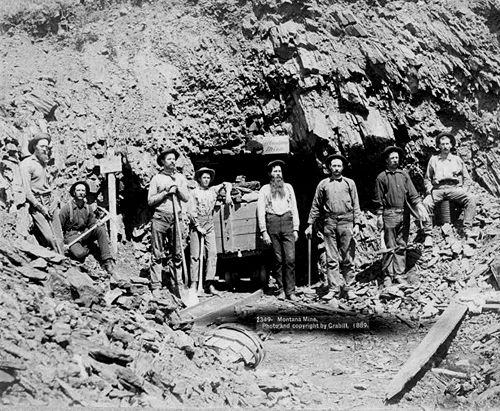

All the camps were very much alike. A straggling row of log cabins or huts of motley construction; a few stores so-called, sometimes of logs, or, if a saw-mill was at hand, of rude sawn boards; several saloons, each of which customarily also supported a dance hall; a series of cabins or huts where dwelt individual men, each doing his own cooking and washing; and outside these huts the uptorn earth — such were the camps which dotted the trails of the stampedes across inhospitable deserts and mountain ranges. The church and school were unknown. The law there was none, for of organized society, there was none. The women who lived there were unworthy of the name of a woman. The men strode about in the loose dress of the camp, sometimes without a waistcoat, sometimes coatless, shod with heavy boots, always armed.

If we look for causes contributing to the history of the mining camp, we shall find one that is ordinarily overlooked—the invention of Colt’s revolving pistol. Though this weapon was not old during the Civil War, it had attained very general use throughout the frontier before the day of modern ammunition.

The six-shooter of the placer days was of the old cap-and-ball type, heavy, long-barreled, and usually wooden-handled. It was the general ownership of these deadly weapons which caused so much bloodshed in the camps. The revolver in the hands of a tyro is not especially serviceable, but it attained great deadliness in the hands of an expert user. Such a man, naturally of quick nerve reflexes, skillful and accurate in using the weapon through long practice, became dangerous and, for a time, an unconquerable antagonist.

It is a curious fact that the great Montana fields were doubly discovered by men coming east from California and, in part, by men passing west in search of new goldfields. The first discovery of gold in Montana was made on Gold Creek by a half-breed trapper named Francois, better known as Be-net-see. This was in 1852, but the news seems to have lain dormant for a time — naturally enough, for there was small ingress or egress for that wild and unknown country. In 1857, however, a party of miners who had wandered down the Big Hole River on their way back east from California decided to look into the Gold Creek discovery, of which they had heard. James and Granville Stuart led this party, including Jake Meeks, Robert Hereford, Robert Dempsey, John W. Powell, John M. Jacobs, and Thomas Adams. These men did some work on Gold Creek in 1858 but seem not to have struck it very rich and to have withdrawn to Fort Bridger in Wyoming until the autumn of 1860. Then, a prospector named Tom Golddigger turned up at Bridger with additional stories of creeks to the north, and there was a gradual straggling back toward Gold Creek and other gulches. This prospector had been all over the Alder Gulch, which would prove to be fabulously rich.

It was not, however, until 1863 that the Montana camps sprang to fame. It was not Gold Creek or Alder Gulch but Florence and other Idaho camps that, in the summer and autumn of 1862, brought into the mountains no less than five parties of gold-seekers, who remained in Montana because they could not penetrate the mountain barrier which lay between them and the Salmon River camps in Idaho.

The first of these parties arrived at Gold Creek by wagon train from Fort Benton, and the second hailed from Salt Lake City. An election was held to form a community organization, the first ever known in Montana. The men from the East brought with them some ideas about law and organization. There were now many good men in the Montana fields, such as the Stuart Brothers, Samuel T. Hauser, Walter Dance, and others later well-known in the State.

These men were prominent in the organization of the first miners’ court, which had occasion to try — and promptly hang — Stillman and Jernigan, two ruffians who had been in from the Salmon River mines only about four days when they thus met retribution for their early crimes.

An associate of theirs, Arnett, had been killed while resisting arrest. The reputation of Florence for lawlessness and bloodshed was well known, and, as the outrages of the well-organized band of desperadoes operating in Idaho might be expected to begin at any time in Montana, a certain uneasiness existed among the newcomers from the States.

Two more parties, likewise bound for Idaho and likewise baffled by the Salmon River range, arrived at the Montana camps in the same summer. Both of these were from the Pike’s Peak country in Colorado. And in the autumn came a fifth — this one under military protection, Captain James L. Fisk commanding and having in the party several settlers bound for Oregon and miners for Idaho. This expedition arrived in the Prickly Pear Valley in Montana on September 21, 1862, having left St. Paul on the 16th of June, traveling by steamboat and wagon train. While Captain Fisk and his expedition pushed on to Walla Walla, nearly half of the immigrants stayed to try their luck at placer mining. But the yield was not great, and the distant Salmon River mines, their original destination, were still waiting for them. Winter was approaching. It was now too late in the season to reach the Salmon River mines, five hundred miles across the mountains, and it was 400 miles to Salt Lake City, Utah, the nearest supply post; therefore, most of the men joined this little army of prospectors in Montana. Some of them drifted to the Grasshopper diggings, soon to be known under the name of Bannack — one of the wildest mining camps of its day.

These different origins of the population of the first Montana camps are interesting because they indicate a difference in the two currents of the population, which now met here in the new placer fields. In general, the wildest and most desperate of the old-time adventurers, those coming from the West, had been located in the Idaho camps and might be expected in Montana at any time. In contrast to these, the men lately out from the States were of a different type, many of them sober, most of them law-abiding, men who had come out to better their fortunes and not merely to drop into the wild and licentious life of a placer camp. Law and order always did prevail eventually in any mining community. In the case of Montana, law and order arrived almost synchronously with lawlessness and desperadoism.

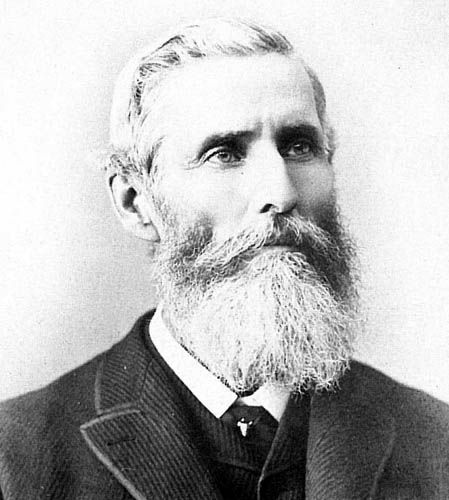

Henry Plummer.

Law and order had not long to wait before the notorious Henry Plummer and his band from Florence, Idaho, arrived. Plummer was already known as a bad man but was not yet recognized as the leader of that secret association of robbers and murderers that had terrorized the Idaho camps. He celebrated his arrival in Bannack, Montana by killing a man named Cleveland. He was acquitted in the miners’ court, which tried him on the usual plea of self-defense. He was a man of considerable personal address.

The same tribunal soon assembled once more to try three other murderers, Moore, Reeves, and Mitchell, with the agreement that the men should have a jury and should be provided with counsel. They were all practically free, and after that, the roughs grew bolder than ever.

The Plummer band swore to kill every man who had served in that court, whether as juryman or officer. So well did they make good their threat that out of the twenty-seven men thus engaged, all but seven were either killed or driven out of the country, nine being murdered outright. The man who had acted as sheriff of this miners’ court, Hank Crawford, was unceasingly hounded by Plummer, who repeatedly sought to fix a quarrel on him. Plummer was the best shot in the mountains at that time, and he thought it would be easy for him to kill his man and enter the usual plea of self-defense.

Sheriff Henry Plummer was hanged from the very gallows that he, himself, had built earlier in the year.

By good fortune, however, Crawford caught Plummer off his guard and fired upon him with a rifle, breaking his right arm. Plummer’s friends called in Dr. Glick, the best physician in Bannack, to treat the wounded man, warning him that if he said anything about the visit, he would be shot down. Glick held his peace and later was obliged to attend many of the wounded outlaws, who were always engaged in affairs with firearms.

Of all these wild affrays, of the savage life which they denoted, and of the stern ways in which retribution overtook the desperadoes of the mines, there is no better historian than Nathaniel P. Langford. A prominent citizen of the West, Langford accompanied the overland expedition of 1862 and took part in Montana’s earliest life. His work, Vigilante Days and Ways is an invaluable contemporary record.

It is mentally difficult for us to restore these scenes fully, although the events occurred no earlier than the Civil War. “Life in Bannack at this time,” says Langford, “was perfect isolation from the rest of the world. Napoleon was not more of an exile on St. Helena than a newly arrived immigrant from the States in this region of lakes and mountains. All the great battles of the season of 1862 — Antietam, Fredericksburg, Second Bull Run — all the exciting debates of Congress and the more exciting combats at sea first became known to us on the arrival of newspapers and letters in the spring of 1863.

The Territory of Idaho, which included Montana and nearly all of Wyoming, was organized on March 3, 1863. Before that time, western Montana and Idaho formed a part of Washington Territory, of which Olympia was the capital, and Montana, east of the mountains, belonged to the Territory of Dakota, of which the capital was Yankton, on the Missouri River. Langford makes clear the political uncertainties of the time and the difficulty of enforcing the laws and narrates the circumstances that led to the erection in 1864 of the new Territory of Montana, comprising the limits of the present State.

In Montana, as elsewhere in these days of great sectional bitterness, there was much political strife, and this no doubt accounts for an astonishing political event that now took place. Henry Plummer, the most active outlaw of his day, was elected sheriff and entrusted with the enforcement of the laws! He made indeed a great show of enforcing the laws. He married and settled down, and for a time, some of the ill-advised thought he should have reformed his ways, although he could not have.

By June 1863, the extraordinarily rich strike in Alder Gulch had been made. The news of this spread like wildfire to Bannack and the Salmon River mines in Idaho, and the result was one of the fiercest of all the stampedes and the rise, almost overnight, of Virginia City. Meanwhile, some Indian fighting had taken place and in a pitched battle on the Bear River where General Connor had beaten decisively the Bannack Indians, who for years had preyed on the emigrant trains. This made travel on the mountain trails safer than it had been, and the rich Last Chance Gulch on which the city of Helena now stands attracted a tremendous population almost immediately. The historian above-cited lived there. Let him tell of the life:

Alder Gulch, Montana.

“One long stream of active life filled the little creek on its auriferous course from Bald Mountain, through a canyon of wild and picturesque character, until it emerged into the large and fertile valley of the Pas-sam-a-ri…the mountain stream called by Lewis and Clark in their journal “Philanthropy River.” Lateral streams of great beauty pour down the sides of the mountain chain, bounding the valley… Gold placers were found upon these streams and occupied soon after the settlement at Virginia City was commenced… This human hive, numbering at least 10,000 people, was the product of ninety days. Into it was crowded all the elements of a rough and active civilization. Thousands of cabins, tents, and brush wikiups were seen on every hand. Every foot of the gulch…was undergoing displacement, and it was already disfigured by huge heaps of gravel which had been passed through the sluices and rifled of their glittering contents… Gold was abundant, and every possible device was employed by the gamblers, the traders, and the vile men and women that had come in with the miners into the locality to obtain it. Nearly every third cabin was a saloon where vile whiskey was peddled out for fifty cents a drink in gold dust. Many of these places were filled with gambling tables and gamblers… Hurdy-gurdy dance-houses were numerous… Not a day or night passed which did not yield its full fruition of vice, quarrels, wounds, or murders. The crack of the revolver was often heard above the merry notes of the violin. Street fights were frequent, and as no one knew when or where they would occur, everyone was on his guard against a random shot.

“Sunday was always a gala day… The stores were all open… Thousands of people crowded the thoroughfares, ready to rush toward any promised excitement. Horse racing was among the most favored amusements. Prize rings were formed, and brawny men engaged in fisticuffs until their sight was lost and their bodies pummeled to jelly while hundreds of onlookers cheered the victor… Pistols flashed, bowie knives flourished, and braggart oaths filled the air as often as men’s passions triumphed over their reason. This was indeed the reign of an unbridled license, and men who at first regarded it with disgust and terror, by constant exposure, soon learned to become a part of it and forget that they had ever been aught else. All classes of society were represented at this general exhibition. Judges, lawyers, doctors, and even clergymen could not claim an exemption. Culture and religion afforded feeble protection, where allurement and indulgence ruled the hour.”

Virginia City, Montana.

Imagine, therefore, a fabulously rich mountain valley twelve miles in extent, occupied by more than ten thousand men and producing more than ten millions of dollars before the close of the first year! It is a stupendous demand in any imagination. How might all this gold be sent out in safekeeping? We are told that the only stage route extended from Virginia City no farther than Bannack. Between Virginia City and Salt Lake City, Utah, there was an absolute wilderness, wholly unsettled, four hundred and 75 miles in width. “There was no post office in the Territory. Letters were brought from Salt Lake for two dollars and a half each and later in the season for one dollar each. All money at infinite risk was sent to the nearest express office at Salt Lake City by private hands.” Imagine, therefore, a fabulously rich mountain valley 12 miles in extent, occupied by more than 10,000 men and producing more than ten million dollars before the close of the first year! How might all this gold be sent out in safekeeping? We are told that the only stage route extended from Virginia City no farther than Bannack.

Between Virginia City and Salt Lake City, an absolute wilderness was wholly unsettled, 475 75 miles in width. “There was no post office in the Territory. Letters were brought from Salt Lake for two dollars and a half each and later in the season for one dollar each. All money at infinite risk was sent to the nearest express office at Salt Lake City by private hands.”

Practically every man in the new gold fields was aware of the existence of a secret band of well-organized ruffians and robbers. The general feeling was one of extreme uneasiness. Plenty of men had taken out of the ground considerable quantities of gold and would have been glad to get back to the East with their little fortunes, but they dared not start. Time after time, the express coach, the solitary rider, and the unguarded wagon were held up and robbed, usually with the concomitant of murder. When the miners started out from one camp to another, they took all manner of precautions to conceal their gold dust. We are told that on one occasion, one party bored a hole in the end of the wagon tongue with an auger and filled it with gold dust, thus escaping observation! The robbers learned to know the express agents and always had the advice of every large shipment of gold. It was almost useless to undertake to conceal anything from them, and resistance was met with death. Such a reign of terror, such an organized system of highway robbery, such a light valuing of human life, has been seldom found in any other time or place.

Stagecoach Robbery.

There were, as we have seen, good men in these camps — although the best of them probably let down the standards of living somewhat after their arrival there; but the trouble was that the good men did not know one another, had no organization and scarcely dared at first to attempt one. On the other hand, the robbers’ organization was complete and kept its secrets as the grave; indeed, many and many a lonesome grave held secrets none ever was to know. How many men went out from the Eastern States and disappeared? Their fate always remains a mystery, and it is a part of the untold story of the mining frontier.

There are known to have been 102 men killed by Plummer and his gang; how many were murdered without their fate ever being discovered cannot be told.

Plummer was the leader of the band, but, arch-hypocrite that he was, he managed to keep his own connection with it a secret. His position as sheriff gave him many advantages. He posed as being a silver mine expert, among other things, and often would be called out to “expert” some new mine. That usually meant that he left town to commit some desperate robbery. The boldest outrages always required Plummer as the leader. Sometimes, he would go away on the pretense of following some fugitive from justice. His horse, the fleetest in the country, often was found laboring and sweating at the rear of his house. That meant that Plummer had been away on some secret errand of his own. He was suspected many times, but nothing could be fastened upon him, or there lacked sufficient boldness and sufficient organization on the part of the law-and-order men to undertake his punishment.

Vigilante Notice

We are not concerned with repeating thrilling tales, bloody almost beyond belief, and indicative of incomprehensible depravity in human nature, so much as we are with the causes and effects of this wild civilization which raged here quite alone in the midst of one of the wildest of the western mountain regions. It will best serve our purpose to remember the twofold character of this population and remember that the frontier caught to itself not only ruffians and desperadoes, men undaunted by any risk, but also men possessed of yet steadier personal courage and hardihood. There were men rough, coarse, brutal, and murderous, but against them were other men self-reliant, stern, just, and resolved upon fair play.

That was indeed the touchstone of the entire civilization, which followed the heels of these scenes of violence. It was a fair play that animated the great Montana Vigilante movement and eventually cleaned up the merciless gang of Henry Plummer and his associates. The centers of civilization were far removed. The courts were powerless. In some cases, even the machinery of the law was in the hands of these ruffians. But so violent were their deeds, so brutal, murderous, and unfair, that slowly, the indignation of the good men arose to the white-hot point of open resentment and swift retribution. What the good men of the frontier loved most of all was justice. They now enforced justice in the only way left open to them. They did this as California earlier had done, and they did it so well that there was small need to repeat the lesson.

The actual extermination of the Henry Plummer band occurred rather promptly when the vigilantes once got underway. One of the band by the name of Red Yager, in company with yet another by the name of Brown, had been concerned in the murder of Lloyd Magruder, a merchant of the Territory. The capture of these two followed closely upon the hanging of George Ives, also accused of more than one murder. Ives was an example of the degrading influence of the mines. He was a decent young man until he left his home in Wisconsin. He was in California from 1857 to 1858. When he appeared in Idaho, he seemed to have thrown off all restraint and become a common rowdy and desperado. It is said of him that “few men of his age ever had been guilty of so many fiendish crimes.”

Yager and Brown, knowing the fate that Ives had met, gave up hope when they fell into the hands of the newly organized vigilantes. Brown was hanged; so was Yager, but Yager, before his death, made a full confession which put the vigilantes in possession of information they had never yet been able to secure.

Langford gives these names disclosed by Yager as follows: “Henry Plummer was chief of the band; Bill Bunton, stool pigeon and second in command; George Brown, secretary; Sam Bunton, roadster; Cyrus Skinner, fence, spy, and roadster; George Shears, horse thief and roadster; Frank Parish, horse thief, and roadster; Hayes Lyons, telegraph man, and roadster; Bill Hunter, telegraph man and roadster; Ned Ray, council-room keeper at Bannack City; George Ives, Stephen Marshland, Dutch John (Wagner), Alex Carter, Whiskey Bill (Graves), Johnny Cooper, Buck Stinson, Mexican Franks Bob Zachary, Boone Helm, Clubfoot George Lane, Billy Terwiliger, Gad Moore were roadsters.” Practically all these were executed by the vigilantes, with many others, and eventually, the band of outlaws was entirely broken up.

Much has been written and much romanced about the conduct of these desperadoes when they met their fate. Some of them were brave, and some proved cowards at the last. For a time, Plummer begged abjectly, his eyes streaming with tears. Suddenly, he was smitten with remorse as the whole picture of his past life appeared before him. He promised everything, begged everything, if only life might be spared him — asked his captors to cut off his ears, to cut out his tongue, then strip him naked and banish him. At the very last, however, he seems to have become composed. Stinson and Ray went to their fate, alternately swearing and whining. Some of the ruffians faced death boldly. More than one himself jumped from the ladder or kicked from under him the box, which was the only foothold between him and eternity. Boone Helm was as hardened as any of them. This man was a cannibal and murderer. He seems to have had no better nature whatever. His last words as he sprang off were, “Hurrah for Jeff Davis! Let her rip!” Another man remarked calmly that he cared no more for hanging than for drinking a glass of water. But each after his own fashion met the end foreordained for him by his own lack of compassion, and of compassion, he received none at the hands of the men who had resolved that the law should be established and should remain forever.

There was an instant improvement in the social life of Virginia City, Bannack, and the adjoining camps as soon as it was understood that the vigilantes were afoot. Langford, who undoubtedly knew intimately of the activities of this organization, makes no apology for the acts of the vigilantes. However, they did not have back of them the color of the actual law. He says:

“The retribution dispensed to these daring freebooters in no respect exceeded the demands of absolute justice… There was no other remedy. Practically the citizens had no law, but if law had existed it could not have afforded adequate redress. This was proven by the feeling of security consequent upon the destruction of the band. When the robbers were dead the people felt safe, not for themselves alone but for their pursuits and their property. They could travel without fear. They had reasonable assurance of safety in the transmission of money to the States and in the arrival of property over the unguarded route from Salt Lake. The crack of pistols had ceased, and they could walk the streets without constant exposure to danger. There was an omnipresent spirit of protection, akin to that omnipresent spirit of the law which pervaded older and more civilized communities…Young men who had learned to believe that the roughs were destined to rule and who, under the influence of that faith, were fast drifting into crime shrunk appalled before the thorough work of the Vigilantes. Fear, more potent than conscience, forced even the worst of men to observe the requirements of society, and a feeling of comparative security among all classes was the result.”

Naturally, it was not the case that all the bad men were thus exterminated. From time to time, there appeared vividly amid these surroundings additional figures of solitary desperadoes, each to have his list of victims, and each himself to fall before the weapons of his enemies or to meet the justice of the law or the sterner need of the vigilantes. It would not be wholly pleasant to read even the names of a long list of these; perhaps it will be sufficient to select one, the notorious Joseph Slade, one of the “picturesque” characters of whom a great deal of inaccurate and puerile history has been written. The truth about Slade is that he was a good man at first, faithful in the discharge of his duties as an agent of the stage company. Needing at times to use violence lawfully, he then began to use it unlawfully. He drank and soon went from bad to worse. At length, his outrages became so numerous that the men of the community took him out and hanged him. His fate taught many others the risk of going too far in defiance of law and decency.

What has been true regarding the camps of Florence, Bannack, and Virginia City had been true in part in earlier camps and was to be repeated perhaps a trifle less vividly in other camps yet to come. For instance, the Black Hills gold rush, which came after the railroad but before the Indians were entirely cleared away, made a certain wild history of its own. We had our Deadwood stage line then and our Deadwood City with all its wildlife of drinking, gambling, and shooting — the place where more than one notorious bad man lost his life, and some capable officers of the peace shared their fate. To describe in detail the life of this stampede and the wild scenes ensuing upon it is perhaps not needful here. The main thing is that the great quartz lodes of the Black Hills support, in the end, a steady, thrifty, and law-abiding population.

All over that West, once so unspeakably wild and reckless, there now rise great cities where recently were scattered only mining camps scarce fit to be called units of any social compact. It was but yesterday that these men fought and drank and dug their own graves in their own sluices. At the city of Helena, on the site of Last Chance Gulch, one recalls that not so long ago, citizens could show with a certain contemporary pride the old dead tree once known as “Hangman’s Tree.” It marked a spot that might be called a focus of the old frontier. Around it, and in the country immediately adjoining, was fought out the great battle whose issue could not be doubted — that between the new and the old days; between law and order and individual lawlessness; between the school and the saloon; between the home and the dance-hall; between society united and resolved and the individual reverted to worse than savagery.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2024.

Also See:

Henry Plummer – Sheriff Meets a Noose

Mining on the American Frontier

About the Author: Excerpted from the book The Passing of the Frontier, A Chronicle of the Old West, by Emerson Hough, Yale University Press, 1918. Emerson Hough (1857–1923) was an author and journalist who wrote factional accounts and historical novels of life in the American West. His works helped establish the Western as a popular genre in literature and motion pictures. For years, Hough wrote the feature “Out-of-Doors” for the Saturday Evening Post and contributed to other major magazines.