British in the American Revolution

Earning the dubious distinction of being the United States’ first documented serial killers, Micajah “Big” Harpe and Wiley “Little” Harpe were murderous outlaws who operated in Tennessee, Kentucky, Illinois, and Mississippi in the late 1700s. Often referred to as the Harpe Brothers, they were cousins who often passed themselves off as brothers.

Their fathers were Scottish immigrants who had settled in Orange County, North Carolina. Micajah Harpe was born to John Harpe and his wife, while Wiley Harpe, actually named Joshua, was born to John’s brother, William, and his wife. Soon after the arrival of the Harpes in America, they changed the spelling of their original name from “Harpe” to “Harp.”

Growing up near each other, the boys soon took up the nicknames of Big and Little Harp, as Wiley was much smaller than Micajah. The two left North Carolina in 1775 for Virginia, intending to find jobs as slave overseers; however, the American Revolution interrupted their careers. The pair sided with the British, but their interest seemed more in violence and criminal activities than any sense of patriotic duty. Along with other like-minded irregulars, they thrilled in burning farms, raping women, and pillaging the American patriots. When Little Harp attempted to rape a girl in North Carolina, he was shot and wounded by Captain James Wood; however, he survived.

In 1780, the Harpes joined the regular British troops and fought in several battles along the North and South Carolina borders. The following year, they left the army and joined a group of Cherokee Indians, raiding settlements in North Carolina and Tennessee and continuing their pillaging. Taking revenge on Captain James Wood, who had earlier wounded Little Harpe, the pair kidnapped his daughter, Susan Wood, and another girl named Maria Davidson. The women served as wives to the Harpes.

The pair, the brutalized women, and four other men began to make their way to Tennessee. During the trip, a man named Moses Doss had the “audacity” to be over-concerned for the brutalized women. For his concern, he was killed by the Harpes. The group then settled in the Cherokee-Chickamauga village of Nickajack, located southwest of modern-day Chattanooga, Tennessee. For the next dozen years, the Harpes, along with their “wives,” lived in the Indian village. Both captive women became pregnant twice during this time, and their fathers killed their children.

After the British surrendered at Yorktown in 1781, the Chickamauga and a break-away band of Cherokee continued to make war on American patriots, and the Harpes were only too willing to help them, fighting in the Battle of Blue Licks, Kentucky, on August 19, 1782, and other more minor skirmishes.

In September 1794, the Americans planned to take the offensive against the Indians at Nickajack. Still, somehow, the Harpes got wind of the attack and fled before the Patriots wiped out the village. The Harpes and their women then settled down at a new camp nearby, where they stayed for the next nine months, once again pillaging local villages in Tennessee. By spring 1797, they lived in a cabin on Beaver’s Creek near Knoxville. That same year, Little Harpe married a local girl, a minister’s daughter named Sarah Rice, and the other two women became the “wives” of Big Harpe.

Just over a year later, in late 1798, the Harpes would begin their murder spree, one of the most violent in the nation’s history. They first killed two men in Tennessee, one in Knox County and one on the Wilderness Trail. By December, they had moved on to Kentucky, where they killed two traveling men from Maryland. Unlike most outlaws, they seemed more motivated by blood lust than financial gain, often leaving their victims disemboweled, filling their abdominal cavities with rocks, and sinking them in a river.

Murdered Man

Next, a man named John Langford, traveling from Virginia to Kentucky, turned up dead, and a local innkeeper pointed the authorities to the Harpes. The criminal pair was then pursued, captured, and jailed in Danville, Kentucky, but they managed to escape. When a posse was sent after them, the young son of a man who assisted the authorities was found dead and mutilated.

On April 22, 1799, the Kentucky Governor issued a $300 reward on each of the Harpe’s heads. Fleeing northward, the Harpes killed two men named Edmonton and Stump. When they were near the mouth of the Saline River, they came upon three men who were encamped and killed all three. The pair then went to Cave-In-The-Rock in southern Illinois, a river pirate Samuel Mason’s stronghold. In the meantime, the posse aggressively pursued them but, unfortunately, stopped just short of Cave-in-The-Rock.

Along with their wives and three children, the Harpes holed up with the Samuel Mason Gang, who preyed on slow-moving flatboats along the Ohio River. However, though the Mason Gang could be ruthless, even they were appalled at the actions of the Harpes. After the murderous pair began to take travelers to the top of the bluff, stripping them naked and throwing them off, they were asked to leave.

The Harpes then returned to Eastern Tennessee, where they continued their vicious murder spree in earnest. In July 1798, they killed a farmer named Bradbury, a man named Hardin, and a boy named Coffey. Soon, more bodies were discovered, including William Ballard, who had been disemboweled and thrown in the Holton River, James Brassel, whose throat was viciously slashed, was discovered on Brassel’s Knob; and another man named John Tully was also found murdered.

In south-central Kentucky, John Graves and his teenage son were found dead with their heads axed, and in Logan County, the Harpes killed a little girl, a young slave, and an entire family asleep in their camp. In August, a few miles northeast of Russellville, Kentucky, Big Harpe killed his daughter by bashing her head against a tree because the baby was crying.

That same month a man named Trowbridge was found disemboweled in Highland Creek, and when they were given shelter at the Stegall home in Webster County, the pair killed an overnight guest named Major William Love, as well as Mrs. Stegall’s four-month-old baby boy, whose throat was slit when it cried. When Mrs. Stegall screamed at the sight of her infant being killed, she, too, was murdered.

The killings continued as the Harpes fled west to avoid the posse, which included Moses Stegall, whose family the Harpes had killed earlier in the month. While the pair were preparing to kill another settler, George Smith, the posse finally tracked them down on August 24, 1799. Calling for their surrender, the two sped away, but Big Harpe was shot in the leg and the back. The posse soon caught up with him and pulled him from his horse. As he lay dying, he confessed to 20 murders, and Mr. Stegall slowly cut off the outlaw’s head while still conscious. Later, he was hanged on a pole near Henderson, Kentucky at a crossroads. For years, the intersection where the pole stood was called Harpe’s Head.

In the meantime, Little Harpe escaped and soon rejoined the Mason Gang pirates at Cave-in-The-Rock. Four years later, Little Harpe was using the alias of John Setton. When a large reward was offered for the head of their leader, Samuel Mason, Harpe, along with a fellow pirate named James May, killed Mason and cut off his head to collect the money. However, as they presented the head, they were recognized as outlaws and arrested. The two soon escaped but were quickly recaptured, tried, and sentenced to be hanged. In January 1804, they were executed, and their heads were cut off and placed high on stakes along the Natchez Road as a warning to other outlaws.

During their terrible crime spree, the Harpes killed over 40 men, women, and children.

But what happened to the three “wives” of the notorious Harpes?

The women were left at the camp on the day Big Harpe was killed in August 1799. The three women, each having one child, were taken to Henderson and placed in an empty blockhouse. On September 4, all three were charged with being parties to the murders of Mary Stegall, her infant son, James, and Captain William Love. They were bound for trial in Russellville but were tried and released in October.

Sally Rice Harpe returned to Knoxville to be with her father. She later married a highly respected man and raised a large family.

Susan Wood stayed in the Russellville area, where she lived a respectable life. She died in Tennessee.

By then, going by the alias of Betsy Roberts, Maria Davidson married John Huffstutler in September 1803. By 1828, they had moved to Hamilton County, Illinois, where they raised a large family and lived until they died in the 1860s.

After the atrocities committed by the Harpes, many family members changed their names so they wouldn’t be connected with the violent murderers.

~~

Natchez Trace

Big Harpe and The Witch Dance

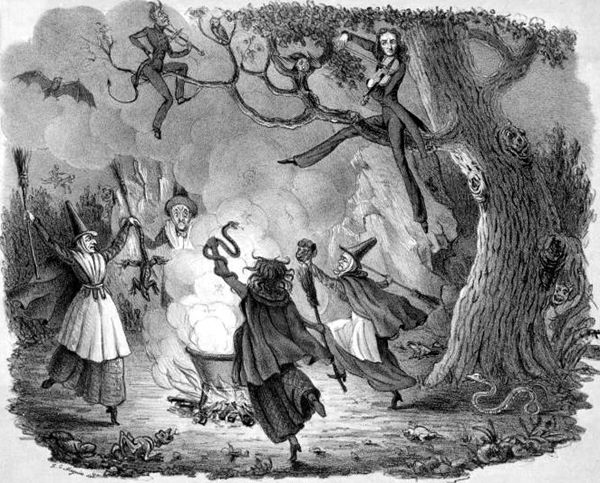

With the violence surrounding the vicious Harpes, it is no surprise that a ghostly legend is attached to the notorious Micajah “Big” Harpe. In addition to terrorizing the states of Kentucky, Tennessee, and Illinois, the Harpes were often known to have traveled along the Natchez Trace through Mississippi. Between Tupelo and Houston, Mississippi, there is a place called Witch Dance. Steeped in mystery for centuries, it was not only the home of the Mound Builders of Mississippi but was also said to have been used by a coven of witches who would gather for nighttime ceremonies. Lore has it that wherever the witches’ feet touched the ground during their dances, the grass would wither and die, never to grow again.

Witch Dance

At some point before his death, Big Harpe was traveling along the Natchez Trace with an Indian guide who showed him the bare spots in the ground and told him of the legend of the Witch Dance. Big Harpe only scoffed at this and began to leap from spot to spot, daring the witches to come out and fight him. Of course, nothing happened, at least not then. Eventually, Big Harpe returned to Kentucky, where the posse tracked him down in August 1799. After he was decapitated and his head placed in the tree, the skull was said to have been removed by a witch, ground into powder, and used as a potion to heal a relative. Word soon got around, and when travelers retold the story along the Trace, they would swear they could hear crackling laughter from nearby bushes and trees.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2023.

Also See: