By Randall Parrish in 1907

Aspects of the Plains about 1840

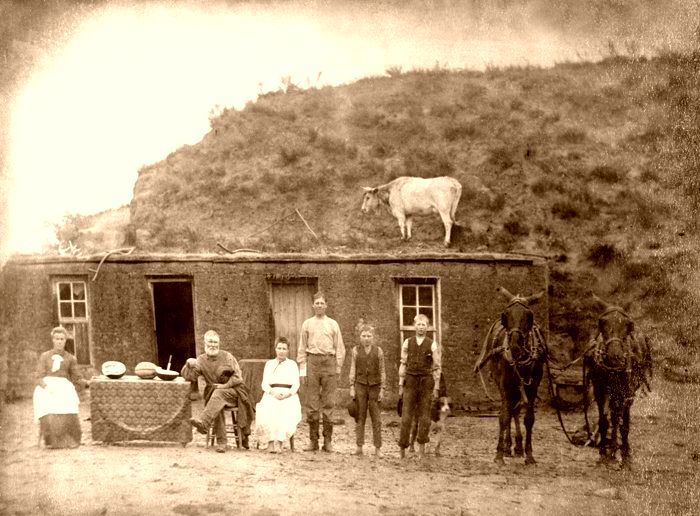

The Great Plains, as they appeared about 1840, now lie outspread before us. To the mass of American citizens living in the Eastern States, that territory was a forbidding desert never to be occupied by man. Only to the adventurers of the border, the hardy trappers, the traders traveling to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and those few army officers who had already penetrated the miles of prairie were its great possibilities vaguely apparent. It was yet barren, desolate, and deserted save for its roaming Indian inhabitants. Much of it remained unknown except to wandering hunters. The long stretch of the Missouri River had been navigated; parties of mountain men had made a passable trail up the Valley of the Platte River; the traders’ caravans had gouged out a road to Santa Fe across prairie and desert; some shanties of logs, and a few stockaded forts, for purposes of Indian trading, were scattered here and there along the larger streams between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains, mere pinpricks in that vast expanse.

In eastern Kansas and Nebraska, a few hardy settlers were already beginning to establish habitations, but these, as yet, scarcely ventured to advance beyond sight of the Missouri River. In Texas, settlements were made possible by a militant advance against Mexico; yet these exercised little if any direct influence over the destinies of the more northern Plains. Because of the need to protect the Santa Fe trade, the government established a military post at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Beyond this, the above-mentioned narrow roads of passage, the Great Plains, remained an abode of savagery, yet to be conquered and reclaimed. Those men and women to whom this gigantic task fell were turning their adventurous eyes westward.

Turning Toward the Northwest and the Southwest

The contest may be said to have fairly begun with the first faint trickle of emigration toward the Pacific coast and to have become stimulated into earnest activity by the results of the struggle with Mexico. The first turned the people’s thoughts toward the permanent settlement of the Northwest; the second brought to men generally a new conception of the possibilities of the Southwest. Thus was the curtain slightly lifted, and the period of exploration verged into the struggle for possession which prefaced permanent habitation. The beginnings of this new movement, although distinct, were slow and uncertain, yet in a comparatively short space of time — as time is reckoned in a nation’s history — the first little wave had swollen into a torrent; the trapper, the trader, the soldier, the emigrant, each, in turn, passed along the dim wilderness trails, leaving the blackened embers of campfires, the deep ruts of wheels, the ghastly relics of battle, yet ever making way for massing settlers behind, constantly broadening out the vista, and making known the truth. This period of Indian Wars and pioneer emigration constitutes the second advance in the story of the Great Plains.

Missionaries Bound for the West

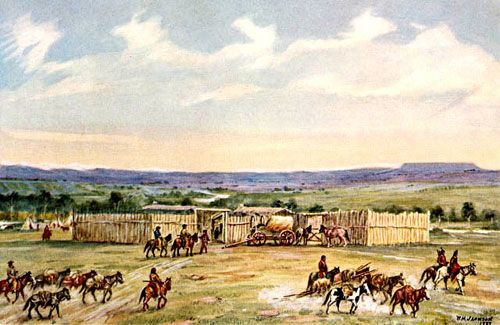

Marcus Whitman founded Waiilatpu Mission in southeastern Washington in 1836. The mission is shown in a painting by William.H. Jackson in 1865.

To tell it right, one must hark back slightly farther than the date set, for as early as 1834, travelers other than traders or trappers passed over the then barely traceable trail leading to distant Oregon. These pioneers of a great movement were missionaries who traveled in small separate parties from that year until 1839. The Lee brothers, Jason and Daniel, passed this way first. The following year Samuel Parker and Marcus Whitman traveled over the long trail. In 1836, Whitman, who had returned East, came back accompanied by his wife, Mr. and Mrs. Spalding, and W. G. Gray; it is said that at the trappers’ rendezvous on the Sweetwater these pioneer white women received a royal welcome at the hands of the gathered mountain men, and were escorted by them some distance on their journey. The remainder of the way, they traveled under the armed protection of the American Fur Company.

The 1838 party was composed of Mr. and Mrs. Walker, Mr. and Mrs. Eells, and Mr. and Mrs. Smith. In 1839 Mr. and Mrs. Griffin, with Mr. and Mrs. Munger, made the journey. These devoted missionaries labored long in the Oregon country, several yielding up their lives for the faith. A few years later, Dr. Whitman made a heroic ride across the mountains and Plains in midwinter, suffering incredible hardships, to bear to Washington the news of the British encroachments on the American settlements on the Columbia River. To his self-sacrifice and patriotism, the Northwest is greatly indebted. Not far behind these earliest forerunners of Protestantism came the Catholic devotee. This was P. J. de Smet, a Jesuit, who, under orders of his Superior, came to the upper Missouri in 1840 to minister to the Indian tribes, and whose life henceforth was devoted to their service.

The early history of Catholic missions in the northern Rockies is little more than the record of this one devoted missionary. Father de Smet traveled extensively over the Plains and mountains and wrote his experiences most interestingly. He was loved by the Indians and never molested, the visits of the ” Black Robe ” always being welcome in the wigwams. His principal labors were among the Salish tribe.

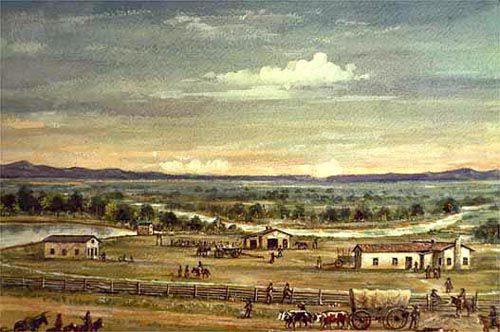

The First Band of Settlers

It was in 1841 that the first band of settlers began crossing the Plains and mountains to Oregon and California. All who had passed that way before were but wanderers, with no settled purpose of peopling this new land. But these were settlers, men, women, and children, and their slow passage westward marked the beginning of a new era decisively. They toiled slowly up the valley of the Platte, finding their only halting place in all those thousands of miles the rude fur trader’s fort on Laramie River. These were truly the pioneers, and they were so few, only fifteen; Joel P. Walker, wife, sister, three sons, and two daughters; Mr. Burrows, wife and child; Mr. Warfield, wife and child, and a man named Nichols. The loneliness, the terrors, the wonders of that journey to the women and children peering out from under the wagon covers as they moved on through those weary months can scarcely be imagined.

Close behind them toiled over the same dim trail Bidwell’s company bound for California, but at Fort Bridger, this party turned more directly west, following the route later made famous by the gold hunters. Mrs. Kelsey was the only woman in the Bidwell company. So in the same year, the first emigrants passed over the long trails to Oregon and California.

Succeeding Bands

From this date, the stream constantly increased in volume. In 1842 a company of one hundred and twelve men, women, and children, under the command of Elijah White, went through to the Columbia River. They had a train of 18 great Pennsylvania wagons with cattle, pack-mules, and horses. The following year an army passed that way, consisting of a thousand men, women, and children, bringing draft cattle, herds of cows and horses, farming implements, and household goods. This marked the beginning of the end of the old regime. Never again were things the same either on the plains or amid the mountains. The period of permanent occupancy had begun.

The Mormon Migration

Close upon the heels of these earlier emigrants came the great Mormon migration of 1847. Words can scarcely picture this movement of thousands, in all conditions of life — men, women, and children, — bearing with them all their worldly possessions and for months traveling across the vast Plains, seeking that home which they finally discovered amid the deserts of Utah. Driven from Illinois by enraged citizens, leaving behind a deserted city, this body of religious enthusiasts, under the leadership of Brigham Young, struggled through Iowa, suffering torments from the bitter cold of winter, and the floods of spring, until their second winter’s camp was established on the banks of the Elkhorn in Nebraska.

But, this halt was only temporary. April 9, 1847, the advance guard departed westward, and all others were expected to follow as soon as possible. The party was furnished with a wagon, two oxen, two milk cows, and a tent for every ten people. Each wagon was supplied with 1,000 pounds of flour, 50 pounds of rice, sugar, and bacon, 30 beans, 20 dried apples or peaches, 25 of salt, five of tea, a gallon of vinegar, and ten bars of soap. Every able-bodied man was compelled to carry a firearm and do his share of guard duty. The wagons were beds, kitchens, and occasionally boats. The average day’s journey was thirteen miles. This advance company was three months in reaching the valley of Great Salt Lake, which their leader chose as the location for their new home.

Behind them, in great trains, reaching in almost solid procession from the distant banks of the Missouri River, toiled the faithful followers of the prophet. This passing of the disciples of the Church of Latter-Day Saints across the wilderness was one of the most wonderful sights witnessed upon the Great Plains, equaled, it is true, and possibly surpassed, in mere point of numbers a few years later by the rush of gold-seekers to California. Yet, when one considers the difference in organization and purpose, this vast exodus remains almost without parallel in history. Nor did this strange migration cease with the passing of these pioneers.

Earnest missionaries of the faith toiled with unremitting zeal in the Eastern States and Europe, their numerous converts, usually poor in all but religious enthusiasm, pressing westward in a continuous stream across the prairies up to the time of the coming of the railroads.

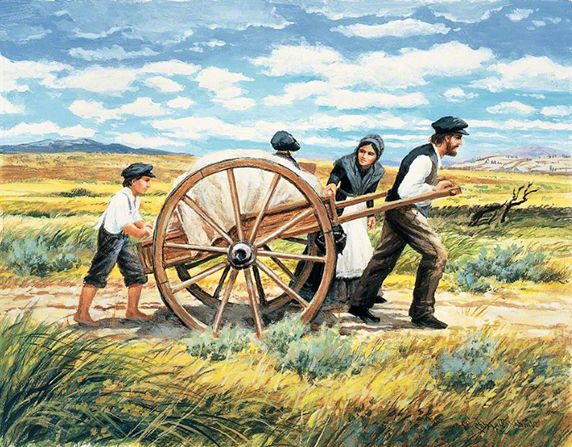

There was no total cessation of the tide. Thousands crossed the Great Plains dragging hand-carts containing their baggage, although the Church authorities provided wagons for the women, children, and sick. These hand-carts were primitive but strong, the shafts five feet long, of hickory or oak, with cross pieces. Under the cart’s bed was a wooden axle tree, the wheels were also made of wood, with a light iron band. The entire weight averaged about sixty pounds.

To every 100 people, the church furnished 20 hand-carts, five tents, three or four milk cows, and a wagon to be drawn by three yokes of oxen. The quantity of clothing and bedding taken was limited to 17 pounds per person, and the freight of each hand cart was expected to be about one hundred pounds.

Route of the Mormons

Mormon Trail Map

The large majority of this Church army traveled westward from Council Bluffs, Iowa, up the valley of the Platte River, following a trail cut deep into the prairie soil. Yet there were side streams from points farther south, the one most used leading from Independence, Missouri, northwest across the Plains until it united with the primary current of travel at Grand Island, Nebraska. This, a little later, became an important route for emigrant trains bound for California and Oregon, and still later was raced over by overland coaches and the Pony Express. Others of the Mormons, although usually traveling in much smaller parties, advanced up the Arkansas River valley and skirted the Rockies’ eastern base on their long journey to the “Promised Land.” Such a company brought the first American families within the present limits of Colorado, residing on the site of Pueblo throughout the Winter of 1846-47.

They erected houses, several children were born, numerous deaths occurred, and there is a record of one wedding. Sufferings on the journey during this passage across the wilderness, much suffering and hardship occurred, but there is no record of an Indian attack. Exposure and death left many along the trails. One large company, having yet a thousand miles to travel, decided to press on as late as the last of November, thus braving a winter on the Plains and in the mountains. At first, they traveled 15 miles a day but were soon delayed by breaking axles and other accidents. At Wood River, their cattle stampeded, and 30 head were lost. The beef cattle, milch cows, and heifers were yoked up but did little service, and the allowance of food was reduced to one meal a day.

They found none reaching Laramie, Wyoming, where they hoped to procure provisions. Again the ration was reduced, men able to work, each receiving 12 ounces of flour daily; women and old men, nine ounces; children, four to eight. The weather grew severe, and they suffered greatly from cold. Before them, loomed the grim mountains already white with snow. The old and infirm began to die, and each camp was a burying ground. Then the able-bodied commenced falling out, some dying in the shafts of their carts. While yet 16 miles from the nearest possible camp on the Sweetwater, it began to snow, and their last ration of flour was issued. At this moment of despair, messengers reached them, saying a train of supplies was only two or three days ahead. Encouraged by this news, the survivors managed to drag forward, but five died of cold and exhaustion during the night.

The next morning the snow was a foot deep, and they had left only two barrels of biscuits, a few pounds of sugar, and dried apples, with a quarter of a sack of rice. They determined to remain in camp, sending forward the captain and one of the elders in search of the supply train. During those three days of waiting, the sufferings of the party were intense. Many were sickened and died. One writer says:

“Some expired in the arms of those who were themselves almost at the point of death. Mothers wrapped with their dying hands the remnant of their tattered clothing around the wan forms of their perishing infants. The most pitiful sight of all was to see strong men begging for the morsel of food that had been set aside for the sick and helpless.”

Late in the night of the third day, the help so long waited to reach them. Yet it came almost too late to save. In Inman’s words:

“Some were already beyond all human aid, some had lost their reason, and around others, the blackness of despair had settled, all efforts to arouse them from their stupor being unavailing. Each day the weather grew colder, and many were frost-bitten, losing fingers, toes, or ears, one sick man, who held on to the wagon bars to avoid jolting, having all his fingers frozen. At a camping ground at Willow Creek, fifteen people were buried, thirteen of them frozen to death.”

Beyond this point, the weather moderated, and when the struggling remnant arrived at Salt Lake, they had a death roll of sixty-seven out of four hundred and twenty. Martin’s party, six hundred strong, journeying a few miles behind, also suffered severely upon the North Platte River but got through with less serious loss of life.

The number passing westward in this Mormon movement has never been estimated, but certain figures can be given as evidence of its importance. The first scouting party, led in person by Brigham Young, numbered 143 men and convoyed a train of 73 wagons. Next behind these followed 1,200 men, women, and children with 397 wagons; then the Kimball company of 662 people and 226 wagons; then those under the charge of Richards, 526 people with 169 wagons.

Increased Migration to Oregon

At the same time, migration to Oregon was steadily increasing. In 1849 1,400 Mormons passed Fort Bridger. A peculiar fact of these early migrations is that few if any, paused en route. Not even rumors of gold deposits in the Black Hills, or the Big Horn Range, halted the current flowing steadily toward Salt Lake and the Pacific. Occasionally a few adventurers were turned aside, yet their discoveries, if any, made no visible mark on history. An illustration is afforded by the story of thirty men deserting Captain Douglas’s party in 1852. They started to prospect in the Black Hills but were never again heard of. Bancroft reports that in 1876 evidence of their work was discovered on Battle Creek, with fragments of skeletons and numerous mining tools. Indians probably killed them.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2022.

About the Author: Adventures and Tragedies on the Overland Trail was written by Randall Parrish as a chapter of his book, The Great Plains: The Romance of Western American Exploration, Warfare, and Settlement, 1527-1870; published by A.C. McClurg & Co. in Chicago, 1907. Parrish also wrote several other books, including When Wilderness Was King, My Lady of the North, Historic Illinois, and others.

Also See:

Westward Expansion and Manifest Destiny

More tales by Randall Parrish:

Adventures and Tragedies on the Overland Trail

Beginning of Settlement in the American West