By Emerson Hough in 1905

One prominent feature of early Western life was the transient and migratory character of the population. It is astonishing what distances were traveled by the bold men who followed the mining stampedes all over the wilderness of the upper Rockies, despite the unspeakable hardships of a region where travel at its best was rude and travel at its worst almost an impossibility. The West was first peopled by wanderers and nomads, even in its mountain regions, which usually attached their population to themselves and cut off the disposition to roam. This nomadic nature of the adventurers made law almost an impossible thing. A town was organized and then abandoned on the spur of necessity or rumor. The property was unstable, taxes impossible, and any corps of executive officers found it difficult to maintain. Before there can be law, there must be an attached population.

Therefore, the lawlessness of the real West was much a matter of conditions, after all, rather than of morals. It proved, above all things, that human nature is very much akin and that good men may go wrong when sufficiently tempted by great wealth left unguarded.

The first and second decades after the close of the Civil War found the great placers of the Rockies and Sierras exhausted and quartz mines taking their place. As has been shown, this same period marked the advent of the great cattle herds from the South upon the upper ranges of the territories beyond the Missouri River. By this time, the plains began to call the adventurers as the mines had recently called.

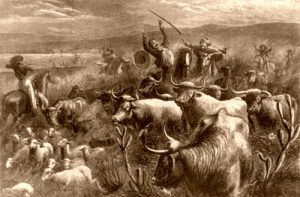

Here, then, was wealth, loose, unattached, apparently almost unowned, nomad wealth, and waiting for a nomad population to share it in one way or another. Once more, the home was lacking, the permanent abode; wherefore, the law was also lacking, and man ruled himself after the ancient savage ways. By this time, frontiersmen were well armed with repeating weapons, which used fixed ammunition. More and better-armed men appeared on the plains than were ever known, unorganized, in any land at any period of the earth’s history, and the plains took up what the mountains had begun in wild and desperate deeds.

The only property on the arid plains was that of livestock. Agriculture had not come, and it was supposed could never come. The vast herds of cattle from the lower ranges, Texas and Mexico, pushed north to meet the railroads, now springing westward across the plains, but a large proportion of these cattle were used as breeding stock to furnish the upper cow range with the horned population. Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, western Nebraska, and the Dakotas discovered that they could raise range cattle as well as the southern ranges and fatten them far better; so presently, thousands upon thousands of cattle were turned loose, without a fence in those thousands of miles, to exist as best they might, and guarded as best might be by a class of men as nomadic as their herds. These cattle were cheap at that time, and they made an available source of food supply much appreciated in a land just depopulated of its buffalo. For a long time, it was but a venial crime to kill a cow and eat it if one were hungry. A man’s horse was sacred, but his cow was not because there were so many cows, and they were shifting and changing about so much at best.

The ownership of these herds was widely scattered and difficult to trace. A man might live in Texas and have herds in Montana and vice versa. His property right was known only by the brand upon the animal, his being but the tenure of a sign.

“The respect for this sign was the whole creed of the cattle trade. Without a fence, without an atom of actual control, the cattleman held his property absolutely. It mingled with the property of others, but it was never confused therewith. It wandered 100 miles from him, and he knew not where it was, but it was surely his and sure to find him. To touch it was a crime. To appropriate it meant punishment. Common necessity made common custom, common custom made common law, and common law made statutory law.”

The old fierro or iron mark of the Spanish cattle owner and his “venta” or sale brand to another had become common law all over the Southwest when the Anglo-Saxons first struck that region. The Saxons accepted these customs as wise and rational, and soon, they were the American law all over the American plains.

The great bands of cattle ran almost free in the Southwest for many years, each carrying the owner’s brand if the latter had ever seen it or cared to brand it. Many cattle roamed free without any brand whatsoever, and no one could tell who owned them. When the northern ranges opened, this question of unbranded cattle still remained, and the “maverick” industry was still held as a matter of sanction; there seems to be enough for all. The day being one of glorious freedom and plenty, the baronial day of the great and once unexhausted West.

Now, the venta, or brand indicating the sale of an animal to another owner, began to complicate matters to a certain extent. A purchaser could put his own fierro brand on a cow, which meant that he now owned it.

But, then some suspicious soul asked, “How shall we know whence such and such cows came, and how to tell whether or not this man did not steal them outright from his neighbor’s herd and put his own brand on them?”

Here was the origin of the bill of sale and the counter brand or “vent brand,” as it is known upon the upper ranges. The owner duplicated his recorded brand upon another recorded part of the animal. This meant his deed of conveyance, when taken together with the bill of sale over his commercial signature. Of course, several conveyances would leave the hide much scarred and hard to read, and, as there were “road brands” also used to protect the property while in transit from the South to the North or from the range to the market, the reading of the brands and the determination of the ownership of the animal might be, and very often was, a nice matter, and one not always settled without argument. Arguments in the West often meant bloodshed in those days. Some hard men started up in trade near the old cattle trails and made a business of disputing brands with the trail drivers. Sometimes, they made good on their claims, and sometimes they did not. There were graves almost in line from Texas to Montana.

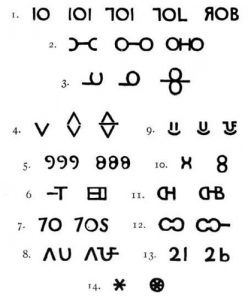

It is now perfectly easy to see what a wide and fertile field was here offered to men who did not want to observe the law. Here was property to be had without work and property whose title could easily be called into question; whose ownership was a matter of testimony and record, to be sure, but testimony which could be erased or altered by the same means which once constituted it a record and sign. The brand was made with an iron, which could be changed with an iron. A large and profitable industry arose in changing these brands. The rustler, brand-burner, or brand-blotcher now became one of the new Western characters, and a new sort of bad-manism had its birth.

“It is very easy to see how temptation was offered to the cow thief and ‘brand blotter.’ Here were all these wild cattle running loose over the country. The imprint of a hot iron on a hide made the creature the property of the brander, provided no one else had branded it before. The time of priority was a matter of proof. With the handy “running iron” or straight rod, which was always attached to his saddle when he rode out, could not the cow thief erase a former brand and put one of his own over it? Could he not, for instance, change a U into an O, or a V into a diamond, or a half-circle into a circle? Could he not, moreover, kill and skin an animal and sell the beef as his own? Between him and the owner was only this little mark. Between him and changing this mark was nothing but his moral principles. The range was very wide. Hardly a figure would show on that un-winking horizon all day long. Avastas a heifer here and there?”

Such was the temptation and opportunity which led many a man to step over the line between right and wrong. Their excuse lies in the fact that the line was newly drawn and often vague and inexact.

It was easy, from killing or re-branding an occasional cow, to see the profits of a more extensive operation. The faithful cowboys who cared for these herds and protected them even with their lives in the interest of absent owners began in time to tire of working on a salary and settled down into little ranches of their own, starting with a herd of cattle lawfully purchased and branded. An occasional maverick came across their range, and they branded it. A brand was faint and not legible, and they put their own iron over it. They learned that pyrography with a hot poker was very profitable. The rest was easy. The first step was the one that counted, but who could tell where that first step was taken? At any rate, cattle owners began to take notice of their cows as the prices went up, and they had laws made to protect property rapidly enhancing in value. Cow owners were required to have fixed or stencil irons and were forbidden to trace a pattern with a straight iron or “running iron.” Each ranch must have its own iron or stencil. Texas, as early as the 1860s, passed laws forbidding the use of the running iron altogether so that after that, it was not safe to be caught riding the range with a straight iron under the saddle flap. Any man so discovered had to do some quick explaining. The next step after this was the organization of cattle associations in several territories and states, which made the home of the cattle trade. These associations banded together in a national association. Detectives were placed at the stockyards in Chicago and Kansas City, charged with finding cattle stolen on the range and shipped with or without clean brands. In short, there had now grown up armed and legal warfare between the cowmen themselves — in the first place, very large-handed thieves — and the rustlers and “little fellows” who were accused of being too liberal with their brand blotching. The prosecution of these men was undertaken with something of the old vigor that characterized the pursuit of horse thieves, with this difference. In contrast, all the world had hated a horse thief as a common enemy; very much of the world found an excuse for the so-called rustler, who was known to be doing only what his accusers had done before him.

There may be a certain interest attached to the methods of the range riders of this day, and those who care to go into the history of the cattle trade in its early days are referred to the work earlier quoted, where the matter is more fully covered.

The rustler might brand with his straight running iron, as it were, writing over again the brand he wished to change, but this was clumsy and apt to be detected, for the new wound would slough and look suspicious. A piece of red-hot haywire or telegraph wire was a better tool, for this could be twisted into the shape of almost any registered brand, and it would so cunningly connect the edges of both that the whole mark would seem to be one scar of the same date.

The fresh burn fitted in with the older one so that it was impossible to swear that it was not a part of the first brand mark. Yet another way of softening a fresh and fraudulent brand was to brand through a wet blanket with a heavy iron, which thus left a wound deep enough but not apt to slough and so betray a brand done long after the round-up, and hence subject to scrutiny.

As to the ways in which brands were altered in their lines, these were many and most ingenious. A sample page will be sufficient to show the possibilities of the art by which the rustler set over to his own herds on the free-range the cows of his far-away neighbor, whom, perhaps, he did not love as himself.

Such, then, was the burglar of the range, the rustler, to whom most of the mysterious and untraceable crimes were ascribed. Such also were the excuses to be offered for some of the men who did what to them did not seem wrong acts. The sudden hostility of the newly-come cow men embittered and inflamed them, and from this, it was easy and natural to the arbitrament of arms.

The bad men of the plains date to this era and his acts may be attributed to these causes. There were to be found among these men many refugees and outlaws, as well as many better men, went wrong through the point of view. Fierce and far were the battles between the rustlers and the cow barons. Commerce had its way at last. The lawless man had to go, and he had to go even before the law had come.

The vigilantes of the cattle range, organizing first in Montana and working southward, made a clean sweep in their work. In one campaign, they killed between 60 and 80 men accused of cattle rustling. They hung thirteen men on one railroad bridge one morning in northwestern Nebraska. The statement is believed to be correct that, in the ten years from 1876 to 1886, they executed more men without the process of law than have been executed under the law in all the United States since then. These lynchings also were against the law. In short, it may perhaps begin to appear to those who study the history of our earlier civilization that the term “law” is a very wide and lax and relative one and one extremely difficult of exact application.

Go To Next Chapter – Wild Bill Hickok

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2023.

About the Author: Excerpted from the book The Story of the Outlaw; A Study of the Western Desperado, by Emerson Hough; Outing Publishing Company, New York, 1907. This story is not verbatim, as it has been edited for clerical errors and updated for the modern reader. Emerson Hough (1857–1923) was an author and journalist who wrote factional accounts and historical novels of life in the American West. His works helped establish the Western as a popular genre in literature and motion pictures. For years, Hough wrote the feature “Out-of-Doors” for the Saturday Evening Post and contributed to other major magazines.

Other Works by Emerson Hough:

The Story of the Outlaw – A Study of the Western Desperado – Entire Text

Cowboys on the American Frontier

The Range of the American West