By Arthur Chapman in 1905

French chivalry never smacked more of an adventure than the little Western towns founded on the devious trail of the longhorn Texas steer to the Northern market during the decade following the Civil War.

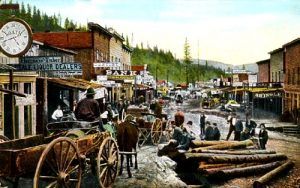

Abilene, Dodge City, Ellsworth, Hays City, Newton — these and more were names that spelled romance in the early days when Kansas was the great clearinghouse for Western cattle, and these small but strenuous places equaled their mining rivals, Deadwood, South Dakota; Tombstone, Arizona; and Leadville, Colorado in their daily clashes of armed men. The streets of the cowtowns were thronged with the hardiest of adventurers. Paris held no more bold-eyed swaggerers and rufflers than the typical cowtown of Abilene when the brief flame of its strangely brought prosperity was at its highest.

Abilene boasted only 200-300 citizens, but the great cattle trail kept the streets swirling with a strange and fearsome floating population. Forty saloons were busy, and between every two saloons was a dance hall, while the back of every barroom was a gambling layout. Night and day, in the long season when the great herds were moving along the trail, wrapped in their dust clouds, mounted cowboys were clattering up and down the streets of Abilene. Rheumatic pianos were tinkling in the dance halls, and the sound of pistol shots frequently came from the saloons and gambling places. Every man had at least one gun slapping at his hips, and every waist felt the sag of a heavy cartridge belt, pregnant with death. Mingling with the cowboys were professional gamblers, men whose false names indicated they were “wanted” back East, “remittance men” from England, wealthy cattle buyers from Chicago and other marketing points, and the painted women and the male riff-raff surrounded them like buzzards scent their feast. This strange and motley gathering crowded the saloons such as the Alamo, the Elkhorn, the Bull’s Head, the Pearl, and other places operated under picturesque names, and the revelry of the boisterous held nightly sway to the accompaniment of numerous powder-burnings.

The nights of riot in Abilene were not more picturesque than the days of intermingled toil and deviltry. The chief hotel was a flimsy structure known as the Drovers’ Cottage. During the heyday of the cattle business, it was run by Colonel I. W. Gore, a hail fellow well met with every cattle owner and cowboy in the Lone Star state and Indian Territory, whence Abilene derived its support. The stockyards were about a quarter of a mile east of the Drovers’ Cottage, and here one could see immense herds of cattle, just off the trail, waiting their turn to be yarded and shipped East by rail. Whooping and yelling, cowboys would be dodging hither and thither on their ponies, dashing into the herds and cutting out 20 or 30 cattle at a time to be weighed. Lariats were swishing; cattle were bawling, and woe to the man who entered this reek of dust and noise on foot, for the Texas steers would turn on such an unfamiliar object instantly and cut it to ribbons with their sharp horns and hoofs.

For several years the trail poured its half-wild cattle and its picturesque men into Abilene and its rival cowtowns, and out of this devil’s pot came a brew of romance that would give the world zestful literature for generations to come.

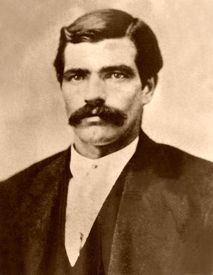

When the few but sturdy citizens of Abilene determined to bring some order out of the riot of their town, laughter resulted. One or two local celebrities who have tendered the Marshalship gave up their badge of authority within a short time. A St. Louis, Missouri man with an excellent reputation as a peace officer looked over the field and left on the next train without talking business. But finally, the office of Marshal was tendered to Thomas J. Smith of Kit Carson, Colorado, and was accepted. Smith was a broad-shouldered, mild-spoken young man who had made himself respected as Marshal of Kit Carson, which was then at the very end of the Kansas Pacific Railroad and which, like all “end towns,” was inclined to disorder. Smith had gone his fearless way among evil men of every description and had first made himself and the law respected. But as soon as it was known along the cattle trail that Smith had been made Marshal of Abilene, there was, figuratively speaking, a flinging of fringed gauntlets into the arena. Placards, calling on all visitors to Abilene to give up their guns when in the town limits, were contemptuously shot to pieces, and finally, conclusions with the new Marshal himself were forced. A bunch of cowboys, headed by a huge bully whose boot tops bore the lone star of Texas, congregated defiantly in front of a saloon with revolvers aggressively displayed.

“You’ll have to give up your guns, boys,” said the new Marshal, advancing toward the leader as he spoke.

Gunfighter

The waxing profanely abusive bully made that back-reaching movement known in the West as a “gunplay,” but he had allowed Smith to come too near. Smith’s big fist shot forward, catching the cowboy full in the jaw and sending him down like a well-roped steer. The science of the prize ring is practically unknown to the average cowboy. Consequently, Tom Smith, an expert boxer, had wisely chosen a method of attack that would prove a surprise. Had he reached for his gun when the bully made his “play,” there is no doubt that Smith’s Marshalship would have ended then and there, and the coming of the law to the cattle county would have been long postponed. But as it was, the cowboys were so amazed at the quickness with which the blow had been struck and the corresponding suddenness with which their champion had sunk senseless to the dust that they could only stand in openmouthed amazement when Smith completed his work by standing over the prostrate Texan and relieving him of his weapons. Nor was there any sign of protest when the new Marshal quietly informed the “boys” that they would have to deposit their weapons at a particular place and at once. The weapons were quietly surrendered to be called for when the cowboys departed, and that day and night, for the first time in its wild career, the cowtown of Abilene was filled with weaponless men. The law had spoken through brave Tom Smith, and the “bad man” reign in the West was no longer undisputed.

For eleven months, Tom Smith “held” Abilene. He did not maintain his place without a struggle, for there were occasional bands of cowboys whose outfits had not heard the Word on the trail that Abilene’s Marshal was not to be trifled with. These boys had to be tamed — but always as Smith had tamed his first bully. When force was to be used, it was Smith, the trained boxer and athlete, and not Smith, the gunfighter, who cut the combs of the swaggering cockerels of Cattledom.

It is said that Smith used his big revolver but once during his reign as Marshal of Abilene, and that was when there was a concerted attempt to assassinate him. The gamblers of the city, who had looked on the coming of the Marshal with none too friendly eyes, had come to regard Smith as a menace to their business. The enforcement of the order regarding firearms surrender had taken some of the zest out of the gambling games. Many cowboys thought no game exciting unless each man had a gun at his hip and a high card in his hand.

“You kin play cards better’n I kin, but blanked if you kin shoot quicker,” was the challenge that led to many an interesting, if the bloody sequel, to Abilene’s sessions at the pasteboards.

When the interests of the gamblers suffered, retaliation was planned. Tom Smith was lured into a room where several gunfighters had been assembled. The lights were to be shot out at a given signal, and Smith was to be killed. But Smith had not walked blindly into the trap. It was his big revolver that spoke first, and it was the same gun that spoke last. When the atmosphere of the smoke-filled room was cleared, three of the Marshal’s assailants were writhing on the floor, and the rest had fled while Smith stood unharmed. It is said that was the only time Tom Smith ever lost his temper. He made his way to the Mayor of Abilene, his face white with wrath and his usually gentle eyes aflame.

Saloon Gunfight

“They set a trap to assassinate me, Mr. Henry,” he said, “and now I’m going after them.”

And he strode out into the hushed streets of Abilene, but the plot’s ringleaders had flown and were never again seen in the sprightly cowtown.

Smith met his death owing to the cowardice of a deputy. A ranchman named McConnell had shot and killed a neighbor, barricaded himself in his log cabin, and defied the authorities. Tom Smith, with one deputy, went to the cabin and burst the door open with his mighty shoulder. McConnell had an ally named Miles, but Smith walked into the cabin unafraid. Miles stepped to the door and snapped a rifle several times at Smith’s deputy, who retreated, though he could have closed with Miles and wrested the useless gun from him. A shot was heard from within the cabin, and the cowardly deputy fled, reporting at Abilene that Smith had been shot. A witness who saw what followed afterward said that Smith brought his man, McConnell, to the cabin door, but here, Miles had turned and struck the Marshal with his clubbed rifle, felling him to the ground. Then Miles and McConnell had dragged the Marshal a few feet from the doorway and severed his head from his body with an ax.

The murderers were captured and brought to Abilene, but thanks to the regard for law and order that Tom Smith had inspired, there was no lynching. One of the prisoners was sentenced to 15 years in the penitentiary and the other to five — indeed light punishment for causing the death of the bravest and most modest of the many brave and modest Marshals of the old West!

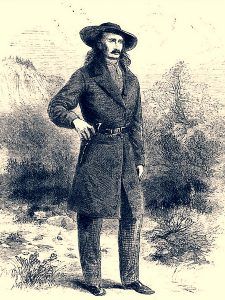

Tom Smith’s successor as Marshal of Abilene was his very antithesis — Wild Bill Hickok. A young correspondent of the New York Herald, Henry M. Stanley by name, whose impressions and experiences in the West helped him immeasurably in his after-work in Africa, called Wild Bill, a child of nature. But instead, Wild Bill was of the stage. A pink-and-white giant with long, shining curls hanging to his shoulders, the very appearance of this hawk-faced artist in gunplay argued of the footlights. No man has ever been one his equal in handling firearms, but once the information was spread abroad that Abilene had a Marshal who was a revolver expert, there was no lack of Doubling Thomases eager to put Wild Bill to the test. Consequently, Hickok’s guns seldom saw a week of silence. Quarrels were picked with him, to encompass his death, but he dropped his man so invariably that finally, none but methods of assassination were employed.

Late in 1871, when several Texans were preparing to return to their State after selling their trail herd at Abilene, an effort was made to put the picturesque Marshal out of the way. A gambler and bully named Phil Coe, who had acquired some reputation in Texas as a man-killer, and who had been drinking heavily in the hope of raising his courage to the point where he could make good his frequent threats against Wild Bill, took a shot at Hickok as the Marshal was leaning against a table in a saloon.

Phil Coe – Old West Gunfighter and Gambler

Wild Bill offered a fair mark, but such was Coe’s trepidation that his shot went wide. Instantly one of Hickok’s guns spoke, and Coe dropped to the sidewalk with a bullet in his abdomen. Rushing into the street, Wild Bill stood over the prone body of his foe. Footsteps were heard, and the Marshal saw the glint of a gun in someone’s hand. Knowing that Coe’s supporters had sworn to kill him at the first opportunity and thinking that the approaching individual was one of the Texans, Wild Bill fired both revolvers. It was a famous trick of his, this shooting right and left from the waistline, and this marvelous marksman never missed his aim with either hand. This time he dropped his man, with two bullet wounds in the breast so close together that they could be covered with the palm of a man’s hand. The man who was shot was Mike McWilliams, a Deputy Marshal of Abilene and one of Wild Bills’ best friends. Wild Bill never got over his remorse at killing McWilliams, and he showed his grief so plainly that the people let him continue as Marshal, though there was some murmuring against a man who made such fatal mistakes.

The cause of Wild Bill’s one significant error in revolver play, Coe lingered a few days but died in agony, cursing his slayer. Coe’s mother offered a standing reward of $10,000 for anyone bringing her the head of Wild Bill Hickok. After learning this, the Abilene Marshal further increased his defenses by adding a sawed-off shotgun. He did not let this weapon out of his grasp, day or night, while he continued in Abilene, for Wild Bill was not only brave but also more cautious than the average gunfighter of his type.

Men came from Texas with the avowed intention of earning a reward. They shadowed Wild Bill, but usually, one glance from those piercing eyes was enough to send them back without any attempt to get the Marshal’s head. On one occasion, when Wild Bill was on a train, he became aware that two men, evidently Texans, were following him. Hickok stepped off the train at Topeka, Kansas, and the men followed him. Wild Bill instantly whirled about, with the sawed-off shotgun at his shoulder, and commanded the men to get back on the train, which they did. The two men were never seen by him again, as their nerve had vanished at the Marshal’s determined front.

Wild Bill did much to keep Abilene in check during his Marshalship. Probably his most significant stroke of public service was when he nipped in the bud one of the raids of the James Gang. Jesse James had planned to attach the receipts of the Abilene fair in 1872 forcibly, but he and his gang were met at the gate by Wild Bill Hickok. With his death-dealing, ivory-handled revolvers aggressively displayed, the very sight of the picturesque Marshal was enough for the entire outfit. The gang decamped without so much as staying to see the fair.

Wild Bill could also be diplomatic on occasion, as he proved when the council of Abilene was debating the question of increasing the license of the saloons in the town. One of the aldermen had made the vote a tie by refusing to put in an appearance. When the case was stated in the council chamber, Wild Bill arose and briefly stated that he would get the man. The alderman had barricaded himself in his office and refused to come forth. Wild Bill hurled his six feet of brawn against the door and tumbled it in. Then he kicked the heels of the alderman from under him and carried the man to the council chamber like a sack of meal. The official was plumped unceremoniously into his chair, with Wild Bill sitting at his elbow, and his vote was duly cast and recorded.

When the cattle trade began to leave Abilene, taking the lawless spirits with it, Wild Bill found his Marshalship to tame an assignment. He resigned and went to the lively mining town of Deadwood, South Dakota, where the lights never went out from sundown to sunrise unless they were shot out. While in a friendly game of cards with an acquaintance, he instantly lost his caution and sat with his back to a door. A big bully named Jack McCall crept through this door and shot Wild Bill in the back. Hickok was dead when he struck the floor, yet those terrible guns of his were half drawn from his belt, so involuntary were this man’s preliminaries to the powder game at which he excelled. And to this day, Deadwood points with pride to the fact that the slayer of Wild Bill was duly and legally hanged.

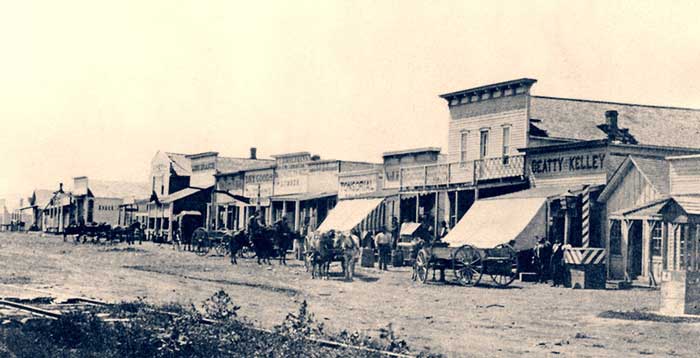

Abilene’s glory as a cowtown diminished in 1872, dividing the trade with Newton, Wichita, Ellsworth, and Dodge City. At Newton, where there was no Marshal to curb the spirits that had chafed under restraint at Abilene, eleven men were killed in one night. But it was in Dodge City that Abilene found a true rival in all that was stirring and picturesque. Here it was that the practice of “setting a killer to kill a killer” was brought to perfection. The authorities took advantage of the experience of Abilene with Wild Bill, and soon it became a regular thing for the man who had gained a reputation as a fearless gunfighter to “try a whirl” at being Sheriff of Ford County, Kansas or Marshal of its metropolis, Dodge City. Here it was that such men as Bat Masterson and his brother Ed, Wyatt Earp, Luke Short, Charley Bassett, Pat Shugrue, George Goodell, Ben Daniels, Ben Thompson, Mayor A. B. Webster, “Mysterious” Dave Mather, Neal Brown, W. H. Harris, and other nervy men took rank among the gunfighters whose names will be famous as long as the traditions of the West endure.

Now the term gunfighter is badly misused by many. Instantly one pictures a swaggering “bad man,” eager to shed blood and not caring if it be the blood of the innocent or of the guilty. But most of these gunfighters of Dodge earned their laurels in the interests of law and order. Ed Masterson, young, alert, and steadfast in his determination to enforce the law as Sheriff, was killed because he requested a party of cowboys to give up their guns as they entered a Dodge City dance hall. Did his brother, Bat, avenge Ed Masterson’s death? He bowled over one after another of the cowboys as they fled across the broad shafts of light from Dodge’s dance hall and saloon doors, and few of the carousing party of murderers managed to get away from town that night. Then Bat became the Sheriff of Ford County and “held” it as well as his brave brother had.

Mayor A. B. Webster, who took up the reins when the revolver was the only sign of law and order that could command respect, was an average citizen who met his duties with the unflinching fidelity the average American citizen generally demonstrates. He even had the credit of disarming Bat Masterson when the former Sheriff of Ford County had returned to Dodge, aided and abetted by one or two gunfighting friends, to “shoot up” specific individuals who had worsted the third Masterson brother, James.

Ben Thompson, one of Dodge’s coterie of gunfighting Marshals, who was a revolver expert second only to Wild Bill, became Marshal of San Antonio, Texas, where he was finally lured into the gallery of a theater and shot by a crowd of enemies in the audience — as dramatic a death as one will find recorded in the annals of the West. Ben’s brother Bill was a murderer, pure and simple, but Ben himself was the ideal of chivalrous courage. Andy Adams, whose book The Log of a Cowboy, tells of Dodge City from the cowboy’s viewpoint, in a letter to the writer, says: “Ben Thompson was a chivalrous gentleman, game to the core and well-liked. I lived in Austin, Texas, when he was City Marshal, and the authorities dispensed with the police force while he held office. Such men were the product of border days, and it certainly was to their credit when they espoused the side of law and order.”

Pat Shugrue, who served two terms as Sheriff of Ford County in the early 1880s, was like Tom Smith of Abilene in that he seldom found it necessary to use his weapons. Shugrue was a brawny little blacksmith with the mysterious power of commanding respect given to few men. The gambling element determined to beat Shugrue at his re-election campaign, as his first administration had been too vigorous to suit the advocates of a “wide open” town. But on election day, there appeared a formidable array of gunfighters at the polls — a group consisting of Luke Short, W. H. Harris, Neal Brown, Wyatt Earp, Charley Bassett, and a fighter named Frank McLean, all headed by Bat Masterson, who was determined that his friend Pat Shugrue should have fair play. The presence of this gun-fighting group of old days acted like magic — the gambling element did not dare put any unfair tactics in play, and a rousing majority elected Shugrue.

The burial ground at Dodge City went by the suggestive name of Boot Hill because so many of its occupants died with their boots on. From Boot Hill, one commanded a view of the straggling little town. Front Street, paralleling the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad tracks, was a line of saloons, dance halls, and gambling houses, and in those trembling shacks of wood were enacted the same coarse pleasures and the same grim tragedies that had marked the life at Abilene a few years before. And through the town extended the influence of the “game” officials who so often had to let their weapons interpret the meaning of the law to the unbelieving and the unregenerate.

The historic streets of Abilene and Dodge City rarely echo the clatter of a cow-pony’s hoofs today. The once-great cattle marts are now prosperous inland cities, surrounded by fertile ranches and conventionally peaceful in their ways. Blue-coated officers of the law club the offender into unconsciousness now, in the approved style of our larger civilization, and the wide-hatted, keen-eyed men whose eloquent revolvers once carried the message of order into Cattledom would have no place amid such surroundings. But the memory of Tom Smith and the other brave officers of frontier days will always endure, for the West can never be ungrateful enough to repudiate its debt to those who first brought the law to the haunts of the lawless.

By Arthur Chapman, The Men Who Tamed the Cowtowns; Outing Magazine, Volume 45, 1905. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2023.

Also See:

Cowboys, Trail Blazers, & Stagecoach Drivers