By Paul R. Petersen, author of Quantrill of Missouri

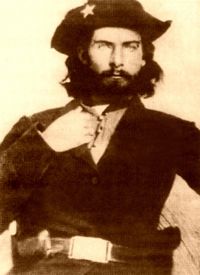

Born in Kentucky in 1839 before moving to Missouri and eventually living in Kansas when the Civil War started, Bill Anderson soon earned the nom de plume “Bloody Bill.”

An unusual event made a guerrilla out of William Anderson. His family had been living in Council Grove, Territory of Kansas, at the start of the war. After William Quantrill’s raid on Aubry, Kansas, on March 7, 1862, a Federal company from Olathe, Kansas, sent a patrol from Company D, Eighth Kansas Jayhawker Regiment, to investigate. Southern sympathizers living nearby were sought out and accused of aiding the raiders. William Anderson’s father and uncle were named as such. When the Jayhawker company arrived at the Anderson farm on March 11, William and his younger brother Jim delivered 15 head of cattle to the U.S. commissary agent at Fort Leavenworth. When the brothers returned to their farm, they found their father and uncle hanged in retaliation, their home burned to the ground, and all their possessions were stolen.

Two days later, Bill and his brother Jim rode with William Quantrill. Anderson removed his sisters from Kansas, where they lived at various places for a year, finally stopping with the Mundy family on the Missouri side of the line near Little Santa Fe. When asked why he joined Quantrill, Anderson replied by saying, “I have chosen guerrilla warfare to revenge myself for wrongs that I could not honorable revenge otherwise. I lived in Kansas when this war commenced. Because I would not fight the people of Missouri, my native State, the Yankees sought my life but failed to get me. [They] revenged themselves by murdering my father, [and] destroying all my property.”

By 1863, all Bill had left was a brother and two sisters that miraculously survived the August 13 Union jail collapse in Kansas City when Union guards from the 9th Kansas Jayhawker Regiment, serving as provost guards in town, intentionally collapsed a three-story brick building on several young Southern female prisoners. Fourteen-year-old Josephine Anderson was killed in the collapse. Bill’s ten-year-old sister Martha’s legs were horribly crushed, crippling her for life, while his 16-year-old sister Molly suffered serious back injuries and facial lacerations. Both girls would carry their battered bodies and emotional scars for years to come.

Anderson soon rose to the rank of captain in Quantrill’s command. He is often accused of brutality and atrocities towards his Union enemies, but Anderson’s own words belie that mistaken belief. In 1864 when Anderson rode east toward Boonville, Missouri, to meet General Sterling Price as he was making his last raid into Missouri, Anderson split up his command to seek food and shelter from sympathizing farmers in the area. Union Major Austin King of the 6th Regiment, Missouri State Militia stationed in Fayette reported that his men, on September 12, killed five of Anderson’s men and captured seven horses and twelve pistols. One was 17-year-old Al Carter, who had moved his family to Howard County from Kansas City because of General Ewing’s General Order No. 11. The other was 17-year-old Buck Collins, who was foraging for food with Carter when they were cut off and surrounded by twenty-five Federals looking for Anderson at a farmhouse. The Federals shot the two men from their saddles. After killing Carter, the soldiers shot out his eyes and then scalped him. Carter had long black curly hair, and the Federals believed they had killed Anderson. The atrocity only showed the deep hatred of the Union troops toward the guerrillas and the brutal deeds of which they were capable.

On September 27, Anderson was camped outside Centralia, Missouri. He took part in his company into town to search for much-needed supplies. A westbound train loaded with 25 Federal soldiers came into view. The guerrillas surrounded the cars. Eyewitnesses at the scene described how the soldiers on board with rifles crowded the windows and the platforms and fired briskly at the guerrillas. Before the firing stopped, Anderson’s men overran the train. The 25 soldiers, most of whom were on furlough from General William T. Sherman’s army, were taken from the train and lined up alongside the platform. Anderson questioned the soldiers and told them how Union troops had recently killed and scalped several men from his command. Anderson, still reeling from the recent loss of his closest men, announced, “You Federals have just killed six of my men, scalped them, and left them on the prairie. I will show you that I can kill men with as much skill and rapidity as anybody. From this time on, I ask no quarter and give none.” Anderson replied, “You are Federals, and Federals scalped my men and carry their scalps at their saddle bows when the soldiers protested. I have never allowed my men to do such things.” One sergeant was singled out and spared for an exchange for one of Anderson’s men recently captured.

Civil War

Anderson has often been accused of having Federal scalps attached to his saddle bows. Research has discovered the truth behind this fabrication. When Anderson rode into Boonville to meet with General Price, another guerrilla leader, John Pringle, accompanied Anderson into town with his own group of partisans.

Pringle and some of his men reportedly had Federal scalps hanging from their horses’ bridle bits. Price ordered the scalps removed before he would talk to the guerrilla leaders. Afterward, Price received Anderson’s report of his summer activities along the Missouri River. In reply, he stated that if he had fifty thousand men such as Anderson, he could hold Missouri for the South indefinitely.

One month later, on October 26, Anderson was killed near Orrick, Missouri, leading a charge against 300 Federals led by Major Samuel P. Cox of the 1st Regiment, Missouri State Militia. Cox’s soldiers cut off Anderson’s finger to steal his wedding ring. After photographing his dead body, they cut off his head and mounted it on top of a telegraph pole in town. Later Anderson’s body was buried in the Old City Cemetery of Richmond, Missouri.

Jayhawker Colonel Charles Jennison’s soldiers from Kansas stopped at the cemetery within a week after Anderson was buried. Southern sympathizers among the local women had carried flowers to decorate the grave. The Jayhawkers seeing the flowers, alighted from their horses. They proceeded to stamp the bouquets into the ground, kicking the soft mound and stamping it down to an even level, resulting in difficulty in later years as to its location. Other accounts report that the Jayhawkers relieved themselves over Anderson’s grave in an act of sheer depravity.

The true explanations surrounding the horrible acts directed towards William “Bloody Bill” Anderson are much more interesting than the irresponsible sensationalized accounts of his actions that his detractors have tried to perpetuate since his death.

© Paul R. Petersen, updated May 2022.

Also See:

Bleeding Kansas and the Missouri Border War

William Quantrill – The Man, the Myth, the Soldier

References:

Kansas City Post, August 21, 1909

Charles H. Lothrop, History of the First Regiment Iowa Cavalry, pg 188.

“Quantrill’s Raiders Recognized by Texas as a Confederate Unit,” Kansas City Star, October 8, 1949.

John Newman Edwards, Noted Guerrillas, pg 293.

Jim Cummins, Jim Cummins’ Book, 1903, reprint, Provo, Utah: Triton Press, 1988.

George Scholl, Letter, collection of Claiborne Scholl Nappier.

Albert Castel, William Clarke Quantrill: His Life and Times, 1962, reprint, Norman: University of Oklahoma, 1999, pg 189.

Moberly (Missouri) Evening Democrat, August 15, 1924.

Official Records of the Rebellion, ser. 1, vol. 41, pt. 4, pg 354.

Paul R. Petersen, Quantrill of Missouri, Cumberland Publishing Co., 2003

Paul R. Petersen, Quantrill in Texas, Pelican Publishing Co., 2007