By Emerson Hough

The Western plains were passed over and left unsettled until the advent of the railroads, which began to cross the plains coinciding with the arrival of the great cattle herds that came up from the South after a market. This market did not wait for the completion of the railroads but met the railroads more than halfway; indeed, it followed them quite across the plains. The frontier sheriff now came upon the Western stage as he had never done before. The bad man also sprang into sudden popular recognition, the more so because he was now accessible to view and within reach of the tourist and tenderfoot investigator. These were palmy days for the Wild West.

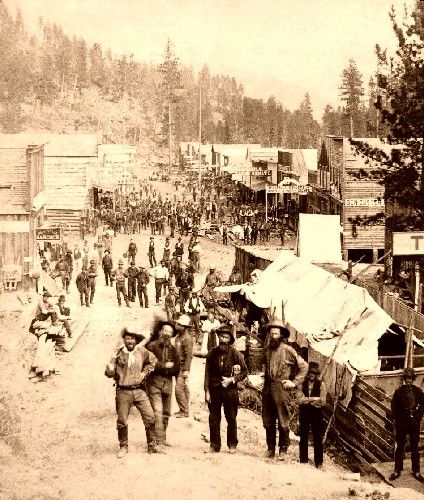

Unless it was a placer camp in the mountains, there is no harder collection of human beings to be found than that which gathers in tents and shanties at a temporary railroad terminus of the frontier. Yet, such were all the capitals of civilization in the earliest days. One town was like another. The history of Wichita, Newton, and Fort Dodge, Kansas, was the history of Abilene, Ellsworth, and Hays City, Kansas, and all the towns at the head of the advancing rails. The bad men and women of one moved on to the next, just as they did in the stampedes of placer days.

To recount the history of one after another of these wild towns would be endless and wearisome. But, this history has one peculiar feature not yet noted in our investigations. All these cowtowns meant to be real towns someday. They meant to take the social compact. There came to each of these camps men bent upon making homes, and these men began to establish a law and order spirit and to set up a government. Indeed, the regular system of American government was there as soon as the railroad was there, and this law was strong on its legislative and executive sides. The frontier sheriff or town marshal was there, the man for the place, as bold and hardy as the men he was to meet and subdue, as skilled with weapons, as willing to die; and upheld, moreover, with that sense of duty and of moral courage which is granted even to the most courageous of men when he feels that he has the sentiment of the majority of good people at his back.

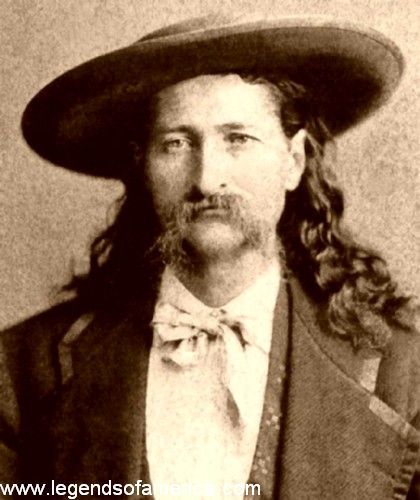

To describe the life of one Western town marshal, himself the best and most picturesque of them all, is to cover all this field sufficiently. There is but one man who can thus be chosen, and that is Wild Bill Hickok, better known for a generation as “Wild Bill,” and properly accorded an honorable place in American history. The real name of Wild Bill was James Butler Hickok, and he was born on May 27, 1837, in La Salle County, Illinois. This brought his youth into the days of Western exploration and conquest, and the boy read of Kit Carson and John Fremont, then popular idols, with the result that he proposed a life of adventure for himself. He was eighteen years of age when he first saw the West as a fighting man under James H. Lane, of Free Soil fame, in the guerrilla days of Kansas before the Civil War. He made his mark and was elected a constable in that dangerous country before he was twenty years of age.

He was a tall, “gangling” youth, six feet one in height, with yellow hair and blue eyes. He later developed into as splendid-looking a man as ever trod on leather, muscular and agile as he was powerful and enduring. His features were clean-cut and expressive, his carriage erect and dignified, and no one ever looked less the conventional part of the bad man assigned in the popular imagination. He was not a quarrelsome man, although a dangerous one, and his voice was low and even, showing a nervous system like that of Daniel Boone — “not agitated.” It might have been supposed that he would be a natural master of weapons, and such was the case. The use of rifle and revolver was born in him, and perhaps no frontier man ever surpassed him in the quick and accurate use of the heavy six-shooter. The religion of the frontier was not to miss, and rarely did he shoot, except he knew that he would not miss. The tale of his killings in single combat is the longest authentically assigned to any man in American history.

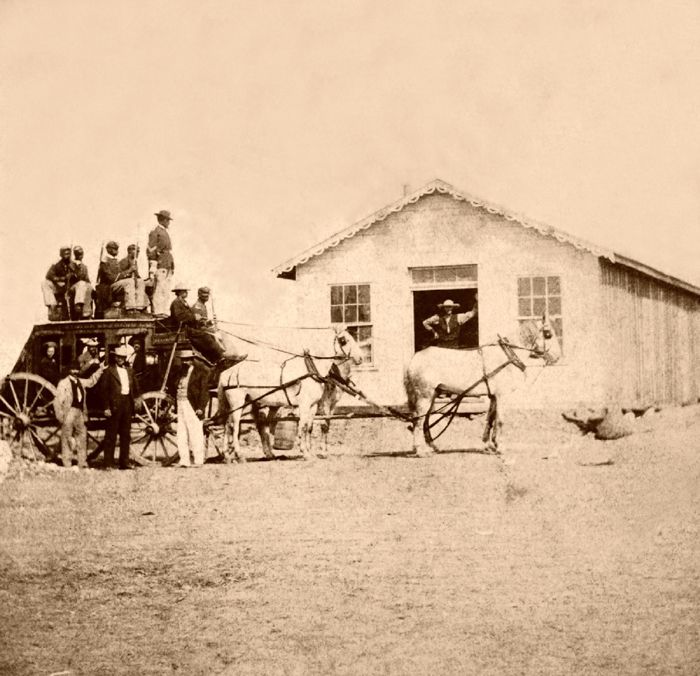

After many experiences with the pro-slavery folk from the border, Bill, or “Shanghai Bill,” as he was then known — a nickname which clung for years — went stage driving for the Overland Stage and incidentally did some effective Indian fighting for his employers, finally, in the year 1861, settling down as station agent for the Overland Stage at Rock Creek Station, Nebraska, about fifty miles from Topeka, Kansas. He was really there as a guard for the horse band, for all that region was full of horse thieves and cutthroats, and robberies and killings were common enough. It was here that occurred his greatest fight, the greatest fight of one man against odds at close range that is mentioned in any history of any part of the world. There was never a battle like it known, nor is the West apt to produce one matching it again.

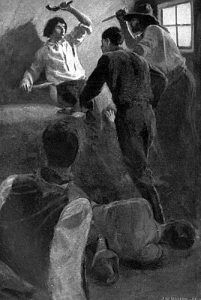

The borderland of Kansas was at that time, as may be remembered, ground debated by the anti-slavery and pro-slavery factions, who still waged a bitter war against one another, killing, burning, and pillaging without mercy. The Civil War was then raging, and Confederates from Missouri were frequent visitors in eastern Kansas under one pretext or another. Horse lifting was the most common, it being held legitimate to prey upon the enemy as opportunity offered. Two border outlaws by the name of the McCanles boys led a gang of hard men in enterprises of this nature, and these intended to run off the stage company’s horses when they found they could not seduce Bill to join their number. He told them to come and take the horses if they could, and on the afternoon of December 16, 1861, ten of them, led by the McCanles brothers, rode up to his dugout to do so. Bill was alone, his stableman being away hunting. He retreated to the dark interior of his dugout and got ready his weapons: a rifle, two six-shooters, and a knife.

The assailants proceeded to batter in the door with a log, and as it fell in, Jim McCanles, who must have been a brave man to undertake so foolhardy a thing against a man already known as a killer, sprang in at the opening. He, of course, was killed at once. This exhausted the rifle, and Bill picked up the six shooters from the table and, in three quick shots, killed three more of the gang as they rushed in at the door. Four men were dead in less than that many seconds, but there were still six others left, all inside the dugout now and firing at him at three feet. It was almost a miracle that, under such surroundings, the man was not killed.

Bill was too crowded to use his firearms and took to the bowie, thrusting at one man and another as best he might. It is known among knife-fighters that a man will stand up under a lot of flesh-cutting and blood-letting until the blade strikes a bone. Then, he seems to drop quickly if it is a deep and severe thrust. In this chance-medley, the knife wounds inflicted on each other by Bill and his swarming foes did not at first drop their men, so it must have been several minutes that all seven of them were mixed in a mass of shooting, thrusting, panting, and gasping humanity. Then Jack McCanles swung his rifle barrel and struck Bill over the head, springing upon him with his knife. Bill got his hand on a six-shooter and killed him just as he would have struck. After that, no one knows what happened, not even Bill, who got his name then and there. “I just got sort of wild,” he said, describing it. “I thought my heart was on fire. I went to the pump to get a drink, and I was all cut and shot to pieces.”

After that, they called him Wild Bill, and he earned the name. There were six dead men on the floor of the dugout. He had fairly whipped the ten of them, and the four remaining had enough and fled from that awful hole in the ground. Two of these were badly wounded. Bill followed them to the door. His weapons were exhausted or not at hand by this time, but his stableman came up just then with a rifle in his hands. Bill caught it from him and, cut up as he was, fired and killed one of the wounded desperadoes as he tried to mount his horse. The other wounded man later died of his wounds. Eight men were killed by the one. The two who got to their horses and escaped were perhaps never in the dugout, for it was hardly large enough to hold another man.

There is no record of any fighting man to equal this. It took Bill a year to recover from his wounds. The life of the open air and hard work brought many Western men through injuries that would be fatal in the States. The pure air of the plains had much to do with this. Bill now took service as wagon master under General Fremont and managed to get attacked by a force of Confederates while on his way to Sedalia, Missouri, the Civil War now in full swing. He fled and was pursued, but, shooting back with six-shooters, killed men. It will be seen that he had now, in a single fight, killed 12 men, and he was very young.

This tally did not cover Indians, of whom he had slain several. Although he did not enlist, he went into the army as an independent sharpshooter just because the fighting was good, and his work at this was very deadly. In four hours at the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, where he lay behind a log on a hill commanding the flat where the Confederates were formed, he is said to have killed thirty-five men, one of them the Confederate General McCullough. It was like shooting buffalo for him. He was charged by a company of the enemy but was rescued by his own men.

Not yet enlisting, Bill went in as a spy for General Curtis and took the dangerous work of going into “Pap” Price’s lines, among the touch-and-go Missourians and Arkansans, in search of information useful to the Union forces. Bill enlisted for business purposes in a company of Price’s mounted rangers, got the knowledge desired, and fled, killing a Confederate sergeant named Lawson in his escape. Curtis sent him back again, this time into the forces of Kirby Smith, then in Texas, but reported soon to move up into Arkansas. Bill enlisted, again and again, showed his skill in the saddle, killing two men as he fled. Count up all his known victims to this time, and the tally would be at least sixty-two men, and Bill was then but 25.

A third time, Curtis sent Bill back into the Confederate lines, this time into another part of Price’s army. Here, he was detected and arrested as a spy. Bound hand and foot in his death watch, he killed his captor after he had torn his hands free and once more escaped. After that, he dared not return again, for he was too well known and difficult to disguise. However, he could not keep out of the fighting and went as a scout and freelance with General Davis during Price’s second invasion of Missouri. He was not an enlisted man and seems to have done pretty much as he liked. One day, he rode out on his own hook and was stopped by three men who ordered him to halt and dismount. All three men had their hands on their revolvers, but to show the difference between average men and a specialist, Bill killed two of them and fatally shot the other before they could get into action. His tally was now sixty-six men at least.

Curtis now sent Bill out into Kansas to look into a report that some Indians were about to join the Confederate forces. Bill got the news and engaged in a knife duel with the Sioux, Conquering Bear, whom he accused of trying to ambush him. It was a fair and desperate fight with knives, and although Bill finally killed his man, he was so badly cut up that he came near dying, his arm being ripped from shoulder to elbow, a wound which it took years to mend. It is doubtful if any man ever survived such injuries as he did, for by this time, he was a mass of scars from pistol and knife wounds. He had probably been in danger of his life more than a hundred times in personal difficulties, for the man with a reputation as a bad man has a reputation that needs continual defending.

After the war, Bill lived from hand to mouth, like most frontier dwellers. It was at Springfield, Missouri, that another duel of his long list occurred, in which he killed Dave Tutt, a fine pistol shot and a man with social ambitions in badness. It was a fair fight in the town square by appointment. Bill killed his man and wheeled so quickly on Tutt’s followers that Tutt did not have time to fall before Bill’s six-shooter was turned the opposite way, and he was asking Tutt’s friends if they wanted any of it themselves. They did not.

This fight was forced on Bill, and his quiet attempts to avoid it and his stern way of accepting it, when inevitable, won him high estimation on the border. Indeed, he was now known all over the country, and his like has not since been seen. He was still a splendid-looking man, as cool, quiet, and modest as ever. Bill now went to trapping in the less settled parts of Nebraska. He lived in peace for a while until he fell into a saloon row over some trivial matter and invited four of his opponents outside to fight him with pistols; the four were to fire at the word, and Bill did the same — his pistol against their four. In this fight, he killed one man at the first fire, but he was shot through the shoulder and disabled in his right arm.

His score was now seventy-two men, not counting Indians. He never reported how many Indians he and Buffalo Bill killed as scouts in the Black Kettle campaign under Carr and Primrose, but the killing of Black Kettle himself was sometimes attributed to Wild Bill. The latter was badly wounded in the thigh with a lance, and it took a long time for this wound to heal. To give this hurt and others a better opportunity for mending, Bill now took a trip back East to his home in Illinois. While in the East, he found that he had a reputation and undertook to use it. However, he found no way of making a living and returned to the West, where he could better market his qualifications.

At that time, Hays City, Kansas, was one of the hardest towns on the frontier. It had more than a hundred gambling dives and saloons to its two thousand population, and murder was ordinary. Hays needed a town marshal and one who could shoot. Wild Bill was unanimously selected, and in six weeks, he was obliged to kill Jack Strawhan for trying to shoot him. This he did because of his superior quickness with the six-shooter, for Strawhan was drawing first. Another bad man, Mulvey, started to run Hays, in whose peace and dignity Bill now felt personal ownership. Covered by Mulvey’s two revolvers, Bill found room for the lightning flash of time, which is all that was needed by the real revolver genius, and killed Mulvey on the spot. His tally was now seventy-five men. He made it seventy-eight in a fight with a bunch of private soldiers, who called him a “long-hair” — a term very accurate, by the way, for Bill was proud of his long, blond hair, as was General Custer and many another man of the West at that time. In this fight, Bill was struck by seven pistol balls and barely escaped alive by flight to a ranch on the prairie nearby. He lay there for three weeks while General Phil Sheridan had details out with orders to get him dead or alive. He later escaped in a box-car to another town, and his days as marshal of Hays were over.

He killed two more with his left hand and badly wounded the other. This was a fair fight, and the only wonder is he was not killed, but he seemed never to consider the odds and literally knew nothing but fight.

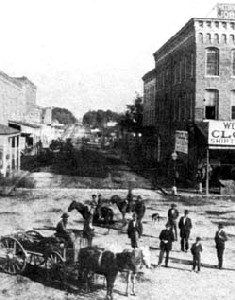

Bill now tried his hand at Wild West theatricals, seeing that already many Easterners were “daffy,” as he called it, about the West, but he failed at this and went back once more to the plains where he belonged. He was chosen marshal of Abilene, then the cow camp par excellence of the middle plains, and as tough a community as Hays had been.

The wild men from the lower plains, fighting men, mad from whiskey and contact with the settlements’ possibilities of long-denied indulgence, swarmed in the streets and dives, mingling with desperadoes and toughs from all parts of the frontier. Those who have never lived in such a community will never be able to understand its phenomena by any description. It seems almost unbelievable that sober, steady-going America ever knew such days, but there they were, and not so long ago, for this was only 1870.

Two days after Bill was elected marshal of Abilene, he killed a desperado who was “whooping up” the town in customary fashion. That same night, in dim light, he was on the street when he saw a man whisk around a corner and saw something shine, as he thought, with the gleam of a weapon. Showing how quickly the hand and eye of the typical gunman of the day, it may be stated that Bill killed this man in a flash, only to find later that it was a friend and one of his own deputies.

The man was only pulling a handkerchief from his pocket. Bill knew that he was watched every moment by men who wanted to kill him. He had his life in his hands all the time. For instance, he had to kill the friend of the desperado whom he had shot. By this time, Abilene respected its new marshal; indeed, it was rather proud of him. The reign of the bad man of the plains was at its height, and the professional man-killer, the specialist with firearms, was a figure here and there over wide regions. Among all these, none compared with this unique specimen. He was generous, too, as he was deadly, for even yet, he was supporting a McCanles widow, and he always furnished funerals for his corpses. He had one more to furnish soon. Enemies down the range among the cowmen made up a purse of five thousand dollars and hired eight men to kill the town marshal and bring his heart back South. Bill heard of it and literally made all of them jump off the railroad train where he met them. One was killed in the jump. His list of homicides was now eighty-one. He had never yet been arrested for murder, and his killing was in a fair, open fight, his life usually against large odds. He was a strange favorite of fortune who seemed certain to shield his roundabout.

Bill now went East for another try at theatricals, in which, happily, he was unsuccessful and for which he felt a strong distaste. He was scared on the stage, and when he saw what was expected of him, he quit and went back to the West again. He appeared at Cheyenne in the Black Hills, wandering thus from one point to another after the fashion of the frontier, where a man did many things and in many places. He had a little brush with a band of Indians and killed four of them with four shots from his six-shooter, bringing his list in red and white to 85 men. He got away alive from the Black Hills with difficulty, but in 1876, he was back again at Deadwood, married now, and, one would have thought, ready to settle down.

But the life of turbulence ends in turbulence. He who lives by the sword dies by the sword. Deadwood was as bad a place as any found in the mining regions, and Bill was not an officer here as he had been in Kansas towns. He had been a national character as a marshal of Hays and Abilene and a United States marshal later at Hays City. He was at Deadwood for the time only plain Wild Bill, handsome, quiet, but ready for anything.

Ready for anything but treachery! He had always fought fair and in the open. His men were shot in front. Not such was to be his fate. On August 2, 1876, while he was sitting at a game of cards in a saloon, a hard citizen named Jack McCall slipped up behind him, placed a pistol to the back of his head, and shot him dead before he knew he had an enemy near. The ball passed through Bill’s head and out at the cheek, lodging in a man’s arm across the table. Bill had won a little money from McCall earlier in the day and won it fairly, but the latter had a grudge and was undoubtedly one of those disgruntled souls who “had it in” for all the rest of the world. At the time, he got away with the killing, for a miners’ court let him go. A few days later, he began to boast about his act, seeing what fame was his for ending so famous a life, but at Yankton, they arrested him, tried him before a real court, convicted him, and hanged him promptly.

Wild Bill’s body was buried at Deadwood, and his grave, surrounded by a neat railing and marked by a monument, long remained one of the features of Deadwood. The monument and fence were disfigured by vandals who sought some memento of the greatest bad man ever in all likelihood seen upon the earth. His tally of eighty-five men seems large, but in fair probability, it is not large enough. His main encounters are known historically. He killed many Indians at different times, but no accurate estimate can be claimed of these. Nor is his list of victims as a sharpshooter in the army legitimately to be added to his record. Cutting out all doubtful instances, however, there remains no doubt that he killed between twenty and thirty men in personal combat in the open and that never once was he tried in any court on a charge even of manslaughter.

This record is not approached by that of any other known bad man. Many of them are credited with twenty men, a dozen men, and so forth, but when the records are sifted, the list dwindles. It is doubted whether any other bad man in America ever actually killed twenty men in fair personal combat. Bill was not killed in a fair fight, nor could McCall have hurt him had Bill suspected his intent.

Hickok was about thirty-nine years old when killed, and he averaged a little more than two men for each year of his life. He was well-known among army officers and esteemed as a scout and a man, never regarded as a tough in any sense. He was a man of singular personal beauty. Of him, General Custer, soon after that falling victim himself upon the plains, said: “He was a plainsman in every sense of the word yet unlike any other of his class. Whether on foot or on horseback, he was one of the most perfect types of physical manhood I ever saw. His manner was entirely free from all bluster and bravado. He never spoke of himself unless requested to do so. His influence among the frontiersmen was unbounded; his word was law. Wild Bill was anything but a quarrelsome man, yet none but himself could enumerate the many conflicts in which he had been engaged.”

These are the words of one fighting man about another, and both men are entitled to good rank in the annals of the West. The praise of an army general for a man of no rank or wealth leaves us feeling that, after all, it was a possible thing for a bad man to be a good man and worthy of respect and admiration, utterly unmingled with maudlin sentiment or weak love for the melodramatic.

Emerson Hough, 1907. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2023.

Go To Next Chapter – Frontier Wars

Notes & Author: Excerpted from the book The Story of the Outlaw – A Study of the Western Desperado, by Emerson Hough; Outing Publishing Company, New York, 1907. This story is not verbatim as it has been edited for clerical errors and updated for the modern reader. Emerson Hough (1857–1923).was an author and journalist who wrote factional accounts and historical novels of life in the American West. His works helped establish the Western as a popular genre in literature and motion pictures. For years, Hough wrote the feature “Out-of-Doors” for the Saturday Evening Post and contributed to other major magazines.

Also See:

Wild Bill Hickok & the Deadman’s Hand

Other Works by Emerson Hough:

The Story of the Outlaw – A Study of the Western Desperado – Entire Text