~~~~

Vulture City, Arizona, once a popular gold mining camp, is a ghost town located at the site of the defunct Vulture Mine in Maricopa County.

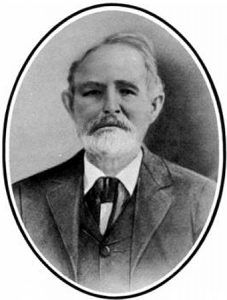

In 1862, Henry Wickenburg, a former California Goldrush prospector, traveled with several other men to look for gold in Arizona. In 1863, he came across a quartz outcropping containing gold. A claim was soon staked and Wickenburg began to work the mine by himself. He named his mine after the many vultures in the area. Before long, however, Wickenburg decided he didn’t want to do the physical work himself and allowed other miners to work the Vulture Mine for a flat fee of $15.00 a ton. Soon, a community developed around the mine, which became known as Vulture City.

In 1866, Henry sold an 80% interest in the mine for $85,000, in exchange for a $20,000 down payment, with the balance to be paid via a promissory note. He moved northward, settling on a ranch site near the town that bears his name today. Another man who came to the area at about the same time was Jack Swilling. A former Confederate officer, Swilling was a visionary who seized the chance to clear out the ancient irrigation canals the Hohokam Indians had dug generations ago near the Salt River Valley. Henry Wickenburg helped to finance the “Swilling Irrigation and Canal Company” in the fall of 1867. The Ditch Project, which later became the Salt River Project, led to the development of central Arizona’s agricultural communities, including Phoenix, as well as providing water for the operation of the Vulture Mine.

By the late 1860s, the Vulture Mine was described as “the largest and richest gold mine” in Arizona. Between 1868 and 1871 the Vulture Mining Company poured money into developing the property and workmen built an office, dwelling house, and a store. At the mill site, they put up offices, a warehouse, a boarding house, and several other buildings. A 12-acre garden was planted along the river to raise vegetables to support about 150 men who were working at the site.

Though the mine was doing well, it was isolated and vulnerable to Indian attacks. In its earliest years, the miners were fortunate because they had little trouble, but that changed in 1868 when the Apache began to harass the miners, forcing the Vulture Mining Company to employ men to escort ore and supply trains traveling to and from the mine. In 1869, most of all the animals were stolen and in September, three men were killed. Apache raids weren’t the only problem at the mine, as many of the miners, millhands, and teamsters were known to be guilty of “high grading,” or stealing gold ore.

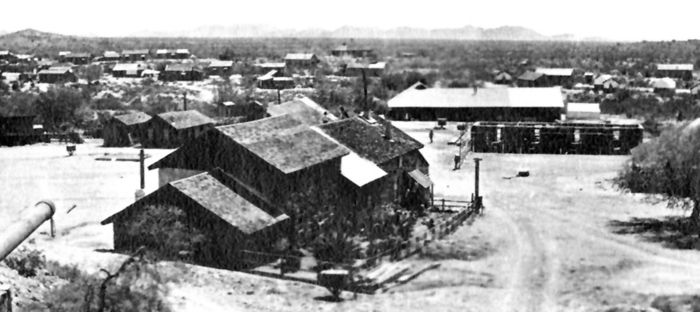

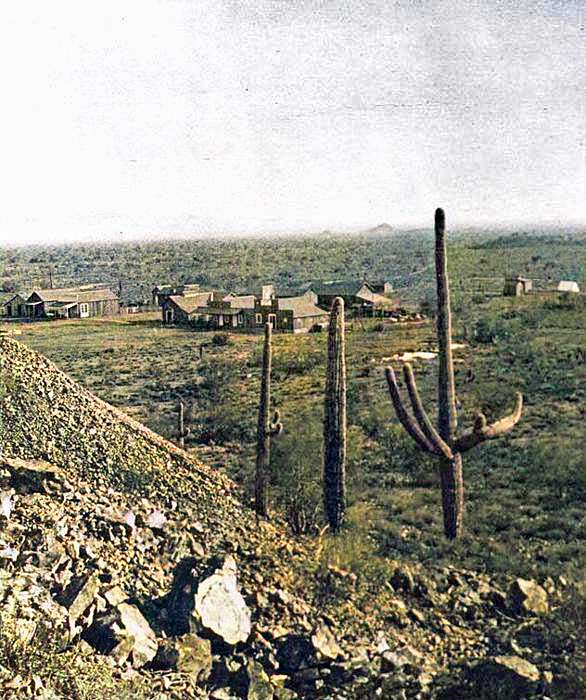

Vulture City, Arizona, 1870s. Touch of color by LOA.

By 1872, the mine’s principal ore body was worked out and during the financial panic of 1873, the Vulture Mining Company, which was heavily in debt closed down the mine and the mill. Up until this time, Henry Wickenburg remained a partner in the operation, though the company never paid on the promissory note, claiming that Wickenburg did not have a clear title to the property. Unfortunately, Henry Wickenburg would not share in the wealth the mine produced.

Over the next several years, there were several attempts made to reopen the mine, as several mining companies probed deeper and worked the old mine tailings.

The building of the Southern Pacific Railroad from Yuma across southern Arizona rekindled more interest in the Vulture Mine as transportation costs had been a major factor in the Vulture Company’s costs. Though the railroad was about 50 miles to the south, investors saw the possibility of branch lines and the future of the mine brightened. In 1878, in walked the Central Arizona Mining Company along with new workmen. In 1880, Vulture City boasted an 80-stamp mill crushing its ore, an assay office, blacksmith shop, several boarding houses, carpenter shop, cookhouse/mess hall, laundry, offices, saloons, stores, multiple small homes, a school, and warehouses. A new pumping plant along the Hassayampa River moved water along a pipeline to the mine. A post office opened in Vulture City on October 4, 1880, with Henry Wickenburg as the first postmaster.

Though the Central Arizona Mining Company had high hopes and predicted positive returns to its investors, they suffered management and financial problems and 1883 was the last year of major operations when the mine produced slightly over $210,000 but paid no dividends to its investors. At this point, Vulture City consisted of several stores, a Wells Fargo office, a post office, a school, and several houses. One writer of the time described the settlement as “a neat village” and praised the town for its free reading hall and Literary Society. In 1884, the Central Arizona Mining Company closed its operations and leased the property. With high debts, the company soon became embroiled in litigation.

The Mine & Assay Office in Vulture, Arizona was built by the Central Arizona Mining Company in 1884. Photo by Kathy Alexander, 2007.

The Mine Office & Assay building in Vulture City, Arizona has been restored today. Photo courtesy Vulture Mine Tours.

In March 1887, famed Leadville, Colorado silver mining millionaire, Horace A. Tabor, purchased the Vulture Mine. For the first time in its history, the mine had an experienced and financially secure owner. However, exactly one year after his purchase, Tabor was stunned by the robbery of a gold shipment on the road from Wickenburg to Phoenix. On March 19th a gang attacked and killed the mine superintendent and two guards, before making off with a gold bar valued at $7,000. Tabor immediately announced that he would pay a $1,000 reward for each bandit captured and the return of the shipment. Territorial authorities also posted a reward and a Maricopa County posse gathered to pursue the robbers. Within just a few days, the posse tracked the bandits, killing one of them, and recovered the gold.

Tabor had most likely purchased the Vulture Mine for speculation and soon leased it out. But, new operators struggled with equipment, flooding, and worker issues. In the meantime, Tabor was having issues at other mines in Colorado when the silver market collapsed, after the Sherman Silver Act, in 1892.

The Territory of Arizona seized the Vulture Mine for back taxes in 1894. In 1896, Tabor leased the mine again, at which time the new operator tore down a number of stone buildings to run the rocks through the mills. Tabor then canceled the lease and put the mine up for sale. However, he couldn’t find a buyer fast enough and in January 1897, the Vulture Mine was sold at a sheriff’s sale. The new owners built a new mill and cyanide plant and reworked tailings and dump material. The post office closed its doors forever in April 1897.

In the meantime, Henry Wickenburg had made a name for himself in Wickenburg, Arizona, and served in the 7th Arizona Territorial Legislative Assembly. He also served in the positions of inspector for the schools, census taker, Justice of the Peace, and judge. Afterward, he retired to his ranch and tried in vain to collect the money owed him by the owners of the Vulture Mine. However, he was not successful and on May 14, 1905, he shot himself and was buried in the Henry Wickenburg Pioneer Cemetery in Wickenburg.

In 1911, the new Vulture Mining Company discovered a new gold vein, and production began in earnest again. But in 1916, the vein was worked out, after producing over four million dollars.

The remains of seven men and 12 burros remain in what is called the Glory Hole in Vulture City, Arizona after a mining accident in 1923. Photo by Kathy Alexander, 2007.

Over the next decades, the mine was worked intermittently. However, tragedy struck in 1923 when seven men died as they were chipping away at support pillars to get to high-grade ore. Unfortunately, the rock holding up the ceiling caused the support to fail and the men, as well as 12 pack animals, were buried under 100 feet of rock. There was no hope of rescue, and their remains continue to be entombed to this day in what is called “The Glory Hole” because the victims were “sent on to glory” during the incident.

In 1942, President Roosevelt issued an executive order during World War II that closed the mine because all resources were to be focused on the war effort. Afterward. Vulture City became a ghost town, but prospectors continued to work the area.

From 1863 to 1942, the mine produced 340,000 ounces of gold and 260,000 ounces of silver, earning some 200 million dollars. Once the most productive gold mine in Arizona, it supported as many as 5,000 residents at its peak.

Today, Vulture City is privately owned but is open to visitors for a fee. Numerous buildings continue to stand, some of which have been restored. The largest building is a rock-walled two-story structure built in 1884 by the Central Arizona Mining Company that served as a mine and assay office. The rocks used to construct the buildings came from the mine, and are thought to contain thousands of dollars worth of gold. This building has been fully restored today.

Other buildings are scattered about including the mess hall, several homes, warehouses, a dynamite building, mill buildings, a blacksmith shop, and an old gas station. Throughout the area can be also be found old mining equipment, ore shafts, and head frames.

Henry Wickenburg’s 15×20 foot cabin, built in the summer of 1864, was constructed with stone and adobe. Completely falling into ruins just a few years ago, it has been restored today. In front of his old cabin is an ironwood tree that is several hundred years old. Here, it said that 18 men were hanged from its branches for high-grading.

One of the most intact ghost towns in Arizona, Vulture City is open daily for tours, except Wednesdays.

Vulture City is located about 12 miles southwest of Wickenburg, Arizona. Travel west from Wickenburg on Highway 60 for about 2.5 miles to Vulture Mine Road, and then head south for about 12 miles, where a sign can be seen to enter Vulture City along 355th Avenue.

For more information, hours of operation, and any special notices, see their official website here.

©Kathy Weiser-Alexander, updated November 2023.

Also See:

Arizona Ghost Town Photo Galleries

Sources:

American Pioneer Cemetery Research

Arizona Family

Smith, Duane A., Arizona and the West, Vol. 14, No. 3, Autumn 1972

Vulture Mine Tours

Wikipedia – Henry Wickenburg

Wikipedia – Vulture City