Mission Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, Zuni

Mission Nuestra Señora de la Asunción, Zia Pueblo

Mission Nuestra Señora de la Purísima Concepción de Quarai, Mountainair

Mission Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles de Porciúncula, Pecos

Mission San Agustin de Isleta, Isleta

Mission San Estevan del Rey de Acoma, Acoma

Mission San Gregorio de Abó, Mountainair

Mission San José de Laguna, Laguna

Mission San Juan Bautista, Ohkay Owingeh

Mission San Miguel de Socorro, Socorro

Mission Santo Domingo, Kewa Pueblo

San Buenaventura de Cochiti, Cochiti

San Buenaventura de las Humanas and San Isidro – Gran Quivira, Mountainair

San Estevan del Rey Mission Church, Acoma

San Francisco de Asís Mission Church, Ranchos de Taos

San Geronimo de Taos, Taos

San José de Gracia de Las Trampas

San José de los Jémez Mission and Gíusewa Pueblo Site

San Lorenzo de Picuris, Picuris

San Miguel Mission, Santa Fe

Santa Clara Mission Church

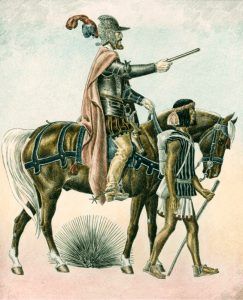

In 1598 Spanish conquistador Juan de Oñate led 400 colonists to the lands along the Rio Grande north of present-day El Paso, Texas, into present-day New Mexico. With him were 1,000 soldiers, 12 Franciscan missionaries, and several Tlaxcalan Mexican Indians. The expedition also included cattle, sheep, goats, oxen, and horses. The colonists were to engage in ranching, and the missionaries provided the local Pueblo Indians with religious instruction. Onate’s mission was clear:

“Your main purpose shall be the service of our Lord, the spreading of His Holy Catholic faith, and the reduction and pacification of the natives of said provinces. You shall bend all your energies to this object without any other human interest interfering with this aim.”

When the missionaries arrived, the New Mexico Pueblos already had a stable economy, elaborate social structures, and a sophisticated religion. However, the Spanish missionaries wanted to eliminate the Puebloans’ religious practices and beliefs and teach them Christianity and European ways.

When Onate and his group arrived at the northern New Mexico Tewa settlement of Owingeh (formerly San Juan Pueblo) in July 1598, the Indians were hospitable. They offered the Yunque-Ouinge pueblo as guest quarters to Oñate and his party. One of the first things the Spanish did was build a church, and the Yunque pueblo became the first Spanish-Catholic capital of Nuevo México.

Onate wasted no time in dispatching small parties of soldiers and Franciscan Friars in all directions to make contact with all of the pueblos in the region. Soon, missions were established in large villages in what has been referred to as “The Golden Age of the Missions.” In 1610, the Spanish capital was moved to La Villa Real de la Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asís, in present-day Santa Fe, New Mexico.

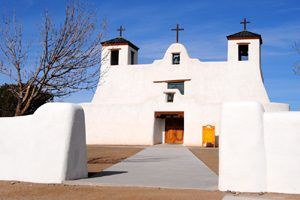

San Francisco de Assisi Mission Church in Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico, still

serves a congregation today.

Mission churches were built of locally available materials and ranged from magnificent adobe buildings at Pecos and Acoma to the equally impressive stone construction of the churches at Jemez and the southern New Mexico pueblos of Quari, Abo, and Gran Quivira. The typical mission church included an artio, a walled yard in front of the church that sometimes served as a cemetery. One or two corner towers flanked the front walls of most missions, usually topped by a wooden cross and a bell. The large wooden door at the center of the front wall led into large, windowless interior spaces, usually devoid of benches or seats. Parishioners stood or knelt on the earthen floor. The interior walls were decorated with colorful murals and carved saints or painted hides. Some churches imported ornate altars and beautiful statuary from Mexico.

Along with the mission regiment, the Spanish introduced a form of taxation, feudal in nature, called the encomienda. Under the encomienda, heads of households in each pueblo were required to pay an annual tribute of produce, blankets, or manual labor to support the Spanish settlement’s defense and the pueblos against raiding Plains Indians, the traditional enemies of the pueblos.

The missionaries also attempted to Hispanicize the indigenous peoples and introduced European livestock, fruits, vegetables, and small-scale industry into the Southwest region. They also introduced European diseases that the native people had no immunity to.

By 1630, a status report to the King of Spain mentioned 90 pueblos ministered to by 25 missions with churches. It also stated that 50 priests were serving over 60,000 natives who had “accepted” Christianity.

However, contrary to the official reports, the native population hadn’t “accepted” Christianity or Spanish rule. Adding more tension to the affairs between the Pueblo people and the Spanish was that the Franciscan missionaries and Spanish civil authorities did not always get along. The authorities often blamed inefficiencies on the priests who were heavy-handed with the Indians. The conflict between church and state became a theme for the Spanish administrations that followed. However, Mexico City continued to dispatch more priests, and official Spanish policies and protocols remained unchanged, leaving the Puebloans in the middle.

For decades, the Pueblo people did not outwardly resist the missionaries. However, by the 1670s, famine, disease, and mounting war casualties convinced most Pueblos that they had been wrong to accept the outsiders’ religion. They believed it was time for them to return to their traditional ways.

In August 1680, the frustration had come to a boil, and an alliance of Pueblo warriors led by leader Popé of the Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo attacked the Spanish colonists. In the revolt, 21 of the 33 missionaries were killed, churches were burned, and records were destroyed. The Spanish then fled the area and didn’t return for 12 years.

When the Spanish did return in 1692, the authorities never allowed the priests to have as much power as they once had, but the encomienda, a major cause of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, was abolished in New Mexico.

Though Puebloan warriors destroyed many of New Mexico’s missions during the Pueblo Revolt, the ruins of several have been preserved, and others that survived were rebuilt or restored. Today, these mission churches provide some of the best examples of Spanish colonial architecture in North America.

Acoma Pueblo, one of the oldest continuously settled communities in North America, built San Estevan Rey in Acoma Pueblo in 1629. It was the only mission church in New Mexico to survive the Pueblo Revolt unscathed, making it the most intact, original, 17th-century structure in the United States.

The Pueblo of Isleta built San Agustin in 1613, and it may be the earliest of the extant mission church in New Mexico. Although Pueblo warriors destroyed the original church during the Pueblo Revolt, subsequent restorations have incorporated parts of the original foundation and walls.

Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe in the Pueblo of Zuni was the most distant from the Spanish capital in Santa Fe. The original church was begun about 1627 but was destroyed during the Pueblo Revolt. It has been rebuilt several times since the early 1700s.

San Jose de Gracia in Trampas is not technically a mission church because it was built in 1760 for use by the Spanish settlers and not the Pueblo Indians. The church remains in use by the descendants of the hardy settlers who founded this mountain community more than two hundred years ago.

Santa Cruz de La Cañada is one of the oldest churches built for use by the Spanish settlers. This adobe structure was originally licensed in 1732 and completed in the 1740s. It contains some of the most magnificent examples of locally produced Spanish colonial religious art in the southwest.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated September 2022.

Also See:

List of Missions & Presidios in the United States

Missions & Presidios of the United States

Spanish Missions & Presidios Photo Gallery

Sources:

Encyclopedia.com

National Park Service

New Mexico History

New Mexico Nomad