By John A. Hill and Jasper Ewing Brady in 1898

I’m on intimate terms with one of the biggest robbers in this country. He’s an expert at the business but has now retired from active work. The fact of the matter is, Joe didn’t know he was robbing, at the time he did it, but he got there, just the same, and come mighty nigh doing time in the penitentiary for it, too.

Maybe I’d better commence at the beginning and tell you that I first knew Joe Hogg in ’79, out at the front, on the Santa Fé Trail. Joe hailed from Salt Lake City, Utah, and had run on the Utah Central, which gave him the nickname of “Mormon Joe,” a name he never resented being called, and to which he always answered. I never did really know whether he was a Mormon or not, and never cared; he was a good engineer, that’s about all I cared for. Joe took good care of his engine, wore a clean shirt, and behaved himself — which was doing more than the average engineer at the front did.

I remember, one night, Jack McCabe — “Whisky Jack,” we used to call him — made some mean remark about the Mormons in general and Joe in particular, and Joe replied: “I don’t propose to defend the Mormon faith; it’s as good as any, to my mind. I don’t propose to judge or misjudge any man by his belief or absence of belief. All that I have got to say is, that the Mormon religion is a practical religion. They don’t give starving women a tract, or tramps jobs on the stone-pile.

The women get bread, and the tramps work for pay. Their faith is based on the Christian Bible, with a book added — guess they have as big a right to add or take away as some of the old kings had — bigamy is upheld by the Bible, but has been dead in Utah, for some years. It can’t live for the young people are against it. In Utah, the woman has all the rights a man has, votes, and is a person. (Since cut out of the new constitution.) Before the Gentiles came to Salt Lake, the Mormons had but one policeman, no jail, few saloons, no houses of prostitution — now the Gentile Christian has sway, and the town is full of them. I guess you could argue on the quality and quantity of rot-gut whisky a good engineer ought to drink, better than on theology, anyhow.”

I never heard any of the gang twit Joe about the Mormons again.

I didn’t take an awful sight of notice about Joe until I came in, one night, and the boys told me that Joe was arrested as an accomplice in the robbery of the Black Prince mine, in Constitution Gulch.

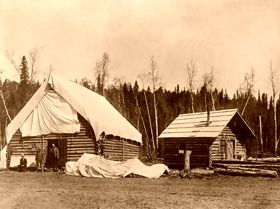

This Black Prince was a gold placer owned by two middle-aged Englishmen. They had a small stamp mill, run by mule power; and a large number of sluice-boxes. They always worked alone and said they were developing the mine. No one had any idea that they were taking out much dust until the mill and sluice-boxes were burned one night, and the story came out that they had been robbed of more than thirty thousand dollars.

Each partner accused the other of the theft. Both were arrested, and detectives commenced to follow every clue.

Joe’s arrest fell like a thunderclap among us. The Brotherhood men took it up right away, and I went to see Joe, that very night. It was said that Joe had visited the Black Prince, the day before, and had been seen carrying away a large package, the night before the robbery.

Joe absolutely refused to say a word for or against himself.

“The detectives got this scheme up and know what they are doing,” said he; “I don’t. When they get all through, you’ll know how it’ll come out.”

To all questions as to his guilt or innocence, to every query about the crime or his arrest, he replied alike, to friend or foe:

“Ask the sheriff; he’s doing this.”

He was in jail a long time, but nothing was proven against him and he was finally released.

Neither of the Englishmen could fasten the crime on his partner, and they sold out and drifted away, one going back to England and the other to Mexico.

Joe ran awhile on the road again and then took a job as chief engineer of a big stamp-mill in Arizona, and going there he was lost to myself and the men on the road, and finally, the Black Prince robbery passed into history, and nothing remained but the tradition, a sort of a myth of the mountains, like Captain Kidd’s treasures, the amount only being increased by time. I believe that the last time I heard the story, it was calmly stated that thirty million dollars were taken.

When I was out West, last time, I got off the train at Santa Fé, and when gunning through the baggage for my kiester, I saw a trunk, bearing on its end this legend:

“MRS. JOS. HOGG.”

While I was “gopping” at it, as they say down East, and wondering if it could be my Joe Hogg, a very nice-looking lady came in, leading a little girl, glanced along the lines of trunks, put her hand on the one I was looking at, and said:

“That’s the one; yes; the little one. I want it checked to New York.”

Just then, a little fellow with whiskers on his chin and a twinkle in his eye came in and took charge of the trunk, the woman and the child, and with the little one’s arms around his neck, bid them goodbye, and got them into their seats in the sleeper.

I watched this individual with a great deal of interest; he looked like my old friend, “Mormon Joe,” only for the whiskers and the stockman clothes.

Finally, he jumped off the moving train, waved his hand and stood watching it out of sight, to catch the last glimpse of (to him) precious burden-bearer; he raised his hand to shade his eyes, and as he did so, I saw that it was minus one thumb, and I remembered that “Mormon Joe” left one of his under an engine up in Colorado — I was sure of him.

There was a tear in his eye, as he turned to go away, so I stepped up to him and asked:

“Any new wives wanted down your way, Elder?”

He glanced up, half angry, looked me straight in the eye, and a smile started at the southeast corner of his phiz and ran around to his port ear.

“Well, John, old man, I don’t mind being sealed to one about your size, right now. I’ve just sent away the best one in the wide world. Old man, you’re looking plump; by the Holy Joe Smith, a sight of you is good for sore eyes!”

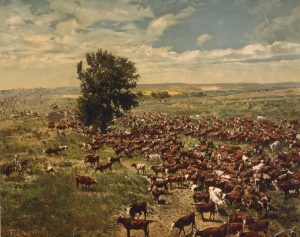

Well, we started, and — but there ain’t no use in telling you all about it — I went home with Joe, went up a creek with a jaw-breaking Spanish name, for miles, to a very good cattle ranch, that was the property of “Mormon Joe.”

Joe only quit running some three or four years ago, and the ranch and its neat little home represented the savings of Joe Hogg’s life.

His wife and only child had just started for a visit to England where she was born.

The next day we rode the range to see Joe’s cattle, and the next we started out for a little hunt. It was sitting by a jolly campfire, back in the hills of New Mexico, that “Mormon Joe” told me the true story of the robbery of the Black Prince mine and the romance of his life.

Filling his cob pipe with cut-plug, Joe sat looking away over space toward our hobbled horses and then said:

“Old man, I reckon you remember all about the Black Prince robbery. I don’t forget you were the first man that came to the cooler to see me while I was doing time as a suspect. Well, coming right down to the point, I had the dust all the time! And the working out of the mystery would be rather interesting reading if it was written up, and, as you are such an accomplished liar, I wouldn’t be surprised if you made it the base-line of one of them yarns of yourn — only, mind you, don’t go too far with it, for it’s as curious as a lie itself. I would not try to improve on it if I was you. I’ll tell it to you as it was.

“About four days before the robbery, I was introduced to Rachel Rokesby, daughter of one of the partners in the Black Prince. I met her, in what seemed to be a casual way, at Mother Cameron’s hash-foundry, but I found out, a long time afterward, that she had worked for two weeks to bring about the introduction.

“I don’t know as you remember seeing her, but she was a quiet, retiring, well-educated, rosy-cheeked English girl — impressed you right away as being the pure, unrefined article, about twenty-two karat. She “chinned” me about an hour, that evening, and just cut a cameo of her pretty face right on my old heart.

“Well, course I saw her home, and tried my best to be interesting, but if a fellow ever in his natural life becomes a double-barreled jackass, it’s just immediately after he falls in love. Why, he ain’t as interesting as the unlettered side of an ore-sack.

“But we got on amazing well; the girl did most of the talking and along toward the last, mentioned that she was in great trouble — of course I wa’n’t interested in that at all. I liked to have broken my neck in getting her to tell me at once if I couldn’t do something to help her, say, for instance, move Raton mountain up agin Pike’s Peak.

“I went home that night, promising to call on her the next trip, not to let anyone know I was coming, not to tell anybody I had been there, not for worlds to repeat or intimate what she told me, and she would tell me her trouble from start to finish, and then I could help her, if I wanted to. Well, I wanted to, bad.

“I went up to the Rokesby’s cabin, next trip in; it was dark, and as I went up the front walk, I heard the old gentleman going out the back, bound for the village ‘diggin’s.’ I had it all to myself — the secret, I mean.

“When I went in, I got about a forty-second squeeze of a neat little hand, and things did look so nice and clean and homelike that I had it on the end of my tongue to ask right then to camp in the place.

“After a few commonplaces, she turned around and asked me if I still wanted to help her and would keep the secret, if I concluded, in the end, to keep out of her troubles. You bet your life, old man, she didn’t have to wait long for assurance — why I wouldn’t’a waited a minute to have contracted to turn the Mississippi into the Mammoth Cave if she had asked it.

“‘Well,” says she, finally, “it is not generally known, in fact, isn’t known at all, that the Black Prince is a paying placer, and that papa and Mr. Sanson have been taking out lots of gold for some time. They have over fifty pounds of gold dust and nuggets hidden under the floor of the old mill.’

“‘Well,’ says I, ‘that hadn’t ought to worry you so.’

“‘But that isn’t all the story,’ she continued; ‘we have discovered a plot on the part of Mr. Sanson to rob papa of the gold and burn the mill and sluice-boxes, to hide the crime. You will find that every tough in town is his friend because he buys whisky for them, and they all dislike papa.

If he carried out his plan, we would have no redress whatever; all the justices in town can be bribed. The plan is to take the gold, burn the mill, and then accuse papa of the crime. Now, can’t you help me to fool that old villain of a Sanson, and put papa’s half of the money in a safe place?’

“I thought quite a while before I answered; it seemed strange to me that the case should be as she stated, and I half feared I might be made a cat’s-paw and get into trouble, but the girl looked at me so trustingly with her blue eyes and added:

“‘I am afraid that I am the cause of all the trouble, too. Papa and Sanson got along well until I refused to marry him; after that, the row began — I hate him. He said I would have to marry him before he was done with me — but I won’t!’

“‘You bet you won’t, darling,’ says I, before I thought. ‘Pardon me, Miss Rokesby, but if there is any marrying done around here, I want a hand in the game myself.’

“She blushed deeply, looked at the toe of her shoe a minute, and said:

“‘I’m only eighteen, and am too young to think of marrying. Suppose we don’t talk of that until we get out of the present difficulties.’

“‘Sensible idea,’ says I. ‘But when we are out, suppose you and I have a talk on that subject.’

“She looked at the toe of her shoe for a minute again, turned red and white around the gills, looked up at me, shyly at first, then fully and fairly, stretched out her hand and said:

“‘Yes; if you care to.’

“Course, I didn’t care, or nothing — no more than a man cares for his head.

“I guess that was about a half engagement, anyhow, it’s the only one we ever had. She said it would be ruinous to our plans if I was seen with her then or afterward; and agreed to leave a note at the house for me by next trip, telling me her plan — which she should talk over with her father.

“A couple of days later I got in from a round trip and made a dive for the boarding-house.

“‘Any mail for me, mother?’ I asked old Mrs. Cameron.

“‘No, young man; I’m sorry to say there ain’t’

“‘I was anxious to hear from home.’

“‘Too bad; but maybe it’ll come tomorrow.’

“I was up to fever heat, but could do nothing but wait. I went to bed late, and, raising up my pillow to put my watch under it, I found a note; it read:

“‘Midnight, July 17.

“‘Dear Joe:

“‘Just thought of that rule for changing counter-balance you wanted. There has always been a miscalculation about the weight of counter-balance; they are universally too heavy. The weights are in pieces; take out two pieces; this treatment would even improve a mule sweep. When once out, pieces should be changed or placed where careless or malicious persons cannot get hold of them and replace them. All is well; hope you are the same; will see you sometime soon.

“‘Jack.’

“Here was apparently a fool letter from one young railroader to another, but I knew well enough that it was from Rachel and meant something.

“I noticed that it was dated the next night; then I commenced to see, and in a few minutes my instructions were plain. The old five-stamp mill was driven by a mule, who wandered aimlessly around a never-ending circle at the end of a long, wooden sweep; this pole extended past the post of the mill a few feet, and had on the short end a box of stones as a counter-weight. I would find two packages of gold there at midnight of July 17.

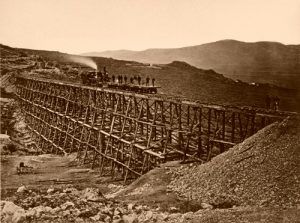

“I was running one of those old Pittsburgh hogs then, and she had to have her throttle ground the next day, but it was more than likely that she would be ready to go out at 8:30 on her turn; but I arranged to have it happen that the stand-pipe yoke should be broken in putting it up so that another engine would have to be fired up, and I would lay in.

“I told stories in the roundhouse until nearly ten o’clock that fateful night, and then started for the hash-foundry, dodged into a lumber yard, got onto the rough ground back of town, and made a wide detour toward Constitution Gulch, the Black Prince and the mule-sweep. I crept up to the washed ground through some brush and laid down on a path to wait for midnight. I felt a full-fledged sneak-thief, but I thought of Rachel and didn’t care if I was one or not, so long as she was satisfied.

“I looked often at my watch in the moonlight, and at twelve o’clock everything was as still as death. I could hear my own heartbeat against my ribs as I sneaked up to that counter-balanced sweep. I got there without accident or incident, found two packages done up in canvas with tarred-string handles; they were heavy but small, and in ten minutes I had them alone with me among the stumps and stones on the little mesa back of town.

“I’ll never forget how I felt there in the dark with all that money that wasn’t mine, and if someone had have said ‘boo’ from behind a stump, I should have probably dropped the boodle and taken to the brush.

“As I approached the town, I realized that I could never get through it to the boarding-house or the roundhouse with those two bundles that looked like country sausages. I studied awhile on it and finally put them under an old scraper beside the road, and went without them to the shops. I got from my seat-box a clean pair of overalls and jacket and came back without being seen.

“I wrapped one of the packages up in these and boldly stepped out into the glare of the electric lights — I remember I thought the town too darned enterprising.

“One of the first men I met was the marshal, Jack Kelly. He was reported to be a Pinkerton man, and was mistrusted by some of the men, but tried to be friendly and ‘stand in’ with all of us. He slapped me on the back and nearly scared the wits out of me. He insisted on treating me, and I went into a saloon and ‘took something’ with him, in fear and trembling. The package was heavy, but I must carry it lightly under my arm as if it were only over clothes.

“I treated in return and had it charged because I dare not attempt to get my right hand into my pocket. Jack was disposed to talk, and I feared he was just playing with me like a cat does with a mouse, but I finally got off and deposited my precious burden in my seat-box, under lock and key — then I sneaked back for the second haul. I met Jack and a policeman, on my next trip, and he exclaimed:

“‘Why, ain’t you gone out yet?’ and started off, telling the roundsman to keep the bunkos off me up to the shop. I thought then I was caught, but I was not, and the bluecoat bid me a pleasant good-night, at the shop yard.

“When I got near my engine, I was surprised to see Barney Murry, the night machinist, with his torch up on the cab — he was putting in the newly-ground throttle.

“Just before I had decided to emerge from the shadow of the next engine, Barney commenced to yell for his helper, Dick, to come and help him on with the dome-cover.