Located on the Santa Fe Trail and the pre-1937 alignment of Route 66, between Pecos and Glorieta, New Mexico, is Pigeon’s Ranch. Portions of the 1862 Civil War Battle of Glorieta Pass were fought here. All that remains of the ranch today is a storied history and a three-room adobe structure situated on the northeast bank of the Glorieta Creek, adjacent to New Mexico Highway 50, about 20 miles southeast of Santa Fe.

This area was part of a land grant issued by the Spanish government to Juan de Dios Pena, Francisco Ortiz, Jr., and Juan de Aguilla in 1815. Later, Juan Estevan Pino purchased the land, and his son sold it to Alexander Valle in 1852 for 5,275 pesos. The land, situated on the north boundary of the Pecos Pueblo Grant, then became known as the Alexander Valle Grant.

Alexander Valle, who also went by the name of Alexander Pigeon, was a French-American born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1817. Along with many others from the St. Louis area, Valle made his way west along the Santa Fe Trail, probably in the late 1830s. Making his living as a Santa Fe Trail trader, he lived in Santa Fe by 1842-43. In 1850, he was still living in Santa Fe with his wife Carmen, where he operated a frontier store that mainly sold liquor. At that time, he was a well-known gambler and land speculator when he turned his attention to the Pecos Valley.

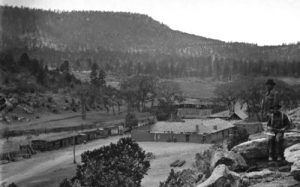

Land records show that he was illiterate, but that didn’t impair his business abilities. Upon his grant, Valle built a large adobe ranch home, a hostel, and a tavern along the Santa Fe Trail. His complex grew to include several buildings, corrals, stables, granaries, and a water well. His inn was said to have had about 22 rooms and was large enough to accommodate as many as 40 people. It was estimated to have been between 70 and 100 feet long in the front with 50-foot wings on the sides. In the front was a broad porch. In the back was a large courtyard.

He also ran cattle and sheep in his fenced-in pastures that stretched for a mile along a nearby creek bottom, as well as a well-cultivated farm. Valle first called his land Rancho de la Glorieta, but it became known as Pigeon’s Ranch.

A stage line had operated in the area since 1850. After Valle established his ranch, it became a stop along the Barlow & Sanderson line, which was running semi-monthly in 1857. By the following year, it was running weekly along his property. Valle brought his last wagon train across the Santa Fe Trail in 1859 and then concentrated on his ranch. His ranch was a popular spot among Santa Fe travelers who described him as a genial, vivacious and obliging, host.

In March 1862, his ranch and inn would be in the path of two advancing Civil War military forces. During the Battle of Glorieta Pass on March 26-28, 1862, both Confederate and Union troops utilized his ranch for various purposes. On March 25, some Confederate troops encamped there, and the next day they were captured. On the 26th, some 400 retreating Union troops established a hasty field hospital at Valle’s ranch and encamped there, utilizing corn, hay, and other supplies from granaries. On the morning of March 27, the Union troops, except for a hospital steward and the wounded, retreated to Kozlowski Trading Post.

With reinforcements having arrived, some 900 Union troops arrived at Pigeon’s Ranch in the morning of the 28th. About an hour later, so did the Confederate Army. Union troops used the adobe fence wall of the compound as cover, and others made their way to Sharpshooter’s Ridge. The Confederate prisoners that were taken, were held at Pigeon Ranch. This battle was occurring while the Valles were in residence, and when they tried to flee, they were captured by Confederate forces.

The Rebels pushed the Union forces out of the area in the late afternoon and took control of Pigeon Ranch. There, they camped until the morning of March 30. Thinking they had won the battle, the Confederates also left the area, moving westward to Johnson’s Ranch, where they found all their supplies and animals had been destroyed by Union forces. This forced them to retreat to Santa Fe, the first step on the long road back to San Antonio, Texas. The Battle of Glorieta Pass was the turning point of the war in New Mexico Territory. In the end, it resulted in 331 total casualties – 142 Union and 189 Confederate.

The use of Valle buildings continued to be utilized as a field hospital by Union stewards into May.

Though Union Major John M. Chivington claimed that the hospital flag he placed on the building on March 26 had protected Valle’s buildings from direct bombardment during the heated fighting on the 28th. However, the main building was caught in the crossfire, damaging walls, doors, windows, and furnishings.

After the Civil War ended, Alexander Valle submitted evidence for reimbursement for goods stolen, damage to his buildings, and household goods destroyed by Union forces during the battle and after. He further claimed that he was a U. S. government forage agent and bought hay and corn from Pecos farms that he sold to government caravans traveling between Fort Union and Fort Marcy. During the battle, he said that 31,000 pounds of corn, 3,000 pounds of fodder, and 10,000 pounds of hay were taken, and cattle on his ranch were killed.

In his claim for damages, Valle reported that he had begun to repair the ranch during the summer of 1862. However, the repairs weren’t completed that summer because Santa Fe Trail travelers reported in 1863 that they had to camp outdoors at Pigeon’s Ranch because the inn repairs were not finished. However, in July 1865, the Senator Dolittle commission stayed at Pigeon’s Ranch during a meeting with Kit Carson, so the inn had obviously been repaired by that time.

In 1865, Alexander Valle sold the Pigeon Ranch to George Hebert and moved to his Valley Ranch just north of Pecos. Valle was ruined financially by the 1870s, either because of the war or his gambling habit. He died at his ranch in June 1880.

George Hebert was a French-Canadian blacksmith who was known to partner in several land deals. He earlier lived in Pecos, where he probably arrived in the 1850s. In the summer of 1865, Jicarilla Apache raided the Pecos Valley, killing two shepherds near the ranch and wounded Hebert. By this time, the Barlow & Sanderson stagecoaches were stopping daily at the ranch, and Hebert’s station was reported to be the largest stop along the Santa Fe Trail from Las Vegas to Santa Fe.

He and his wife, Isabel, continued Valle’s tradition of catering to Santa Fe Trail travelers, and in 1867 a newspaper article reported: “the admirable cuisine and other needful accommodations awaiting the tired and hungry traveler at Mr. George Hebert’s hotel at Pigeon’s Ranch.”

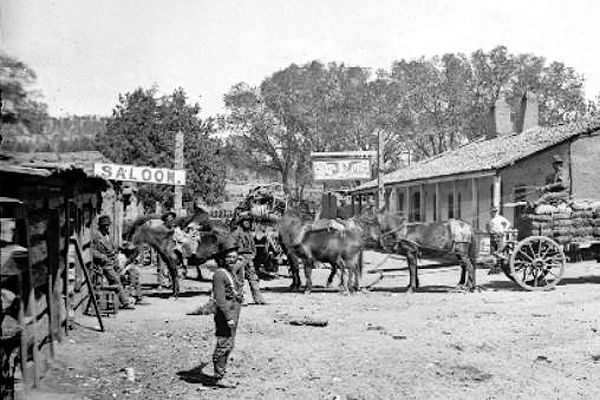

By the late 1870s, the ranch had changed little, but a row of one-story adobe structures had been built on the south side of the trail, one with a saloon sign out front, which catered to travelers and railroad construction workers. At this time, Hebert was also the postmaster for the small community of La Glorieta, and the post office was situated on his ranch.

In 1880, the census reported that 53-year-old Hebert and his wife Isabel and two children lived at the ranch and several boarders, cooks, and laborers. This year, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad was completed over Glorieta Pass in January. At that time, the stagecoach service was discontinued, and the Santa Fe Trail mainly became obsolete. The post office and the businesses across the road then moved to the new railroad station at Glorieta, two miles west. Hebert was probably out of business by the end of the year, as he returned to farming in the Pecos Valley.

Hebert sold the Pigeon Ranch in 1887 to Walter M. Taber, who, along with his family, would live on the land for almost 30 years. It is unknown what happened to the ranch between owners Hebert and Taber, but it was probably leased. A.B. Wadleigh, Taber’s cousin, who would write about the ranch years later, stated that by the time Taber bought the land, the inn “had a bad name as being the rendezvous of gamblers and other tough characters.” Wadleigh also mentions that Walter M. Taber built another house off the road and engaged in agricultural pursuits. This would account for the reason that the original buildings of the ranch deteriorated during Taber’s tenure.

In August 1906, Walter Taber was appointed postmaster of the Glorieta post office, and mail was once again distributed from the ranch. A visitor noted that the ranch buildings were greatly dilapidated in the same year.

In the 1910 census, 51-year-old, Illinois-born Walter Taber lived on the ranch with his wife Martha and his son Walter, Jr. At that time, he was raising livestock and farming in addition to serving as postmaster. His “Glorieta Mercantile and Livestock Co.” also raised sheep in the area as well as in western Sandoval County. Period photos of the time show a sign attached to the Pigeon Ranch house porch, which advertised the “Glorieta Post Office and Store.” Photos during the 1910s also show that all but the front rooms were collapsed, and the rear portion of the main house square was removed. The adobe wall to the west remained, but the rough log sheds that once stood were also collapsed. All the outbuildings across the wagon road had also disappeared. Taber served as postmaster until 1918 and died soon after, as his wife, Martha Taber, was listed as a widow in the 1920 census.

In the meantime, groups were interested in preserving the battlefield, the graves, and marking historic sites along the Santa Fe Trail. In 1910, the Santa Fe New Mexican editorialized that the Glorieta site should be dedicated as a state park. Though nothing came of this initiative, it did show a desire to preserve the site and probably saved Pigeon’s Ranch from total demolition.

Martha Taber sold Pigeon’s Ranch in 1926 to Thomas Greer, a Pecos Valley cowboy. In 1920, Greer lived at San Jose, some 20 miles downstream from Glorieta. At that time, he was a widower with two young children. He remarried n 1921. He first ran a few cattle and operated a store on the ranch.

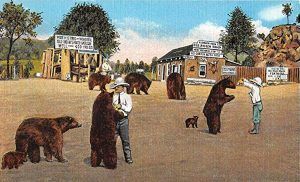

However, when Route 66 came through in 1926, he converted “Pigeon’s Ranch” into a roadside attraction and moved his family into a new home across the road. A visitor log book with a beginning entry of July 14, 1928, indicates that visitors were willing to pay 25 cents to visit the attraction, museum, curio shop. It also suggests that by July 1928, the site featured a full-blown roadside “museum” inside a newly constructed perimeter fence. Photographs of the Greer Ranch attraction appeared in the February 1929 National Geographic and the New Mexico Highway Journal, stating that the “old ranch” was a worthwhile stop.

People paid 25 cents to visit the “Old Hospital” (a remnant of the original building), the “old cave,” “old post office,” “old walls,” and “old Spanish fort,” which were all parts of or remnants of the original Pigeons Ranch compound. Bears were also part of his roadside attraction. Greer also operated a gas station and garage and sold water from the “oldest well” across the road. Alexander Valle built the well in about 1858. On the exterior was an array of signage. Inside the “museum,” the walls were marked up with sayings, poetry, brands, and an odd assortment of stories, as well as artifacts, skins and antlers, and skulls.

When Route 66 was realigned in 1937, it bypassed Santa Fe and Glorieta Pass. This, coupled with travel restrictions during World War II and the realignment of US 85 in the 1950s away from Pigeon’s Ranch, put an end to Greer’s attraction. Afterward, Tom Greer moved his family into the old Kozlowski Trading Post, where he lived until he died in 1968.

The new construction of a “superhighway” over Glorieta Pass in the late 1950s caused the demolition of Johnson’s ranch, regrading the landscape through Apache Canyon, and destruction of battle sites, which brought an outcry from preservationists. In 1861, the Glorieta Battlefield site, including Pigeon’s Ranch, was recognized as one of New Mexico’s first designated National Historic Landmarks. In 1992, the National Park Service acquired Pigeon’s Ranch, which remains undeveloped.

In June 1987, a Confederate mass grave was uncovered during the construction of a new addition to a home across the road from Pigeon’s Ranch.

The burial site contained 31 skeletons that were generally agreed to be Confederate soldiers buried after the Battle of Glorieta Pass. The remains were removed and buried at the National Cemetery in Santa Fe.

The one-story, three-room adobe structure is the western portion of the 1880 main house front. The lone remnant of the former Pigeon’s Ranch complex can be seen immediately adjacent to State Route 50. It is located about a mile southeast of Glorieta.

About 1/2 mile to the southeast of Pigeon’s Ranch on Highway 50 was once another popular stop along old Route 66 — the Arrowhead Camp. Thad and Emma Slaughter established it in 1927. This stop once boasted the main lodge, seven cabins, a store, a service station, a trailer camp, and a cafe. In the 1930s, an overnight stay in one of the cabins cost 50¢, and in the 1940s, it was a popular spot among the locals for dinner and dancing. Though Route 66 was rerouted in 1937, bypassing the site and World War II limited travel, the camp survived, and at some point, the name was changed to the Arrowhead Lodge. The facility opened and closed through a succession of owners in the 1950s and, in the 1960s, became a Methodist church camp. By the 1970s, it was privately owned. All that remains today is the main building remodeled as a residence and a few ruined cabins.

The Santa Fe Trail and Route 66 continue along New Mexico Highway 50 for just about one mile before it crosses over I-25 to the tiny town of Glorieta.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2022.

Also See:

Route 66 Pre-1937 Alignment in New Mexico

Sources:

National Park Service

New Mexico History

Secord, Paul, Pecos (Images of America), Arcadia Publishing 2014

Wadleigh, A. B. Ranching in New Mexico, 1886-1890, New Mexico Historical Review 27, 1952.