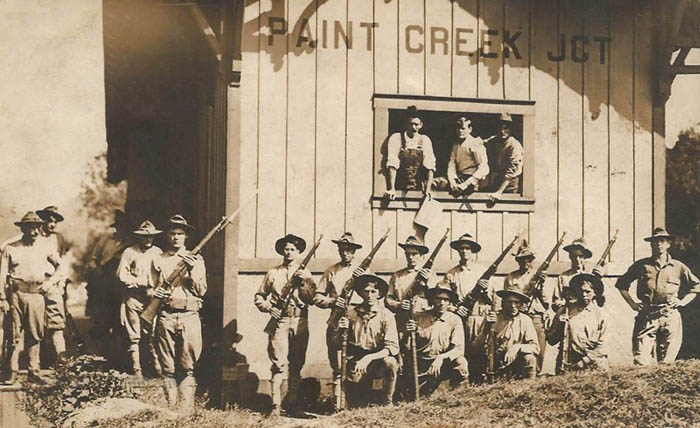

Paint Creek, West Virginia Strikers.

The Paint Creek-Cabin Creek Strike of 1912–13 was one of the most dramatic and bloody conflicts in the southern West Virginia Mine Wars.

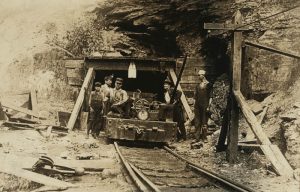

Beginning in the 1890s, coal miners began attempting to organize unions in the coalfields of southern West Virginia to fight the injustices of the coal mine labor system. As was common in most labor struggles of this era, mine owners and operators fiercely resisted the workers’ efforts.

The strike centered in an area enclosed by two streams — Paint Creek and Cabin Creek. Before the strike, there were 96 coal mines in operation on the creeks, employing 7,500 miners. Of these mines, the 41 mines on Paint Creek were unionized, as were all of the mines in the Kanawha River coalfield except for 55 mines on Cabin Creek. However, miners on Paint Creek received compensation of 2.5¢ less per ton than other union miners in the area.

When the Paint Creek miners tried to negotiate a new contract with the operators in 1912, they demanded a pay raise to the same level as the surrounding area. They also wanted the right to trade where they wanted rather than being forced to buy from company-owned stores and recognition of the United Mine Workers (UMW). The pay increase would have cost operators approximately 15 cents per miner per day, but the operators refused.

On April 18, 1912, the conflict came to a head with a “wildcat” strike in which workers launched a work stoppage without union assistance. Soon, 7,500 nonunion miners in nearby Cabin Creek joined them.

While the United Mine Workers (UMW) had not initiated the strike, they were eager to make inroads in the region, so they lent their full support to the striking miners. The union sent both renowned organizers Mary “Mother” Jones and UMW vice president Frank Hayes to the region to assist them. Partly because of the influence of the UMW, the strike was conducted without violence in the first month. This marked the beginning of what has come to be known as the West Virginia mine wars.

The coal operators responded by recruiting strikebreakers from the South and New York. On May 10, 1912, the mine operators hired the notorious Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency to break the strike. Within no time, Baldwin–Felts sent in more than 300 mine guards who provoked the miners.

After the Agents arrived, carrying high-powered rifles, they constructed iron and concrete forts outfitted with machine guns throughout the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek strike area. Another intimidation tactic employed was the Bull Moose Special. This armored train consisted of a locomotive, a passenger car, and an iron-plated baggage car equipped with two machine guns. The Special operated during the fall and winter of 1912, escorting other trains hauling nonunion workers into the strike district.

In response, Socialist Party activists began supplying miners with weapons, including six machine guns, 1,000 high-powered rifles, and 50,000 rounds of ammunition. The mining district quickly became an armed camp.

Afterward, many miners either moved out or were evicted from the houses they had been renting from the coal companies and moved into coal camps supported by the UMW. The Union supplied canvas tents in various sizes, with larger tents serving as makeshift cafeterias or storage areas for provisions. The guards continued to evict mining families from company housing, destroying $40,000 worth of personal property in the process. The guards also enforced the coal mine operators’ control over the region’s company towns, preventing strikers from using bridges across mountain streams or leaving on trains traveling through the area by beating those who attempted to board. Beatings, sniper attacks, and sabotage were daily occurrences.

As the force of the guards increased, the miners fought back. Violence often centered around the trains coming to and from the coal towns that often carried strike-breaking scab workers to keep the mines open. Sometimes miners would destroy train tracks and fire on the trains while the mine guards and policemen attacked and fired on the miners from the train cars.

Through July, Mother Jones rallied the workers, persuaded another group of miners in Eskdale, West Virginia, to join the strike, and organized a secret march of 3,000 armed miners to the steps of the state capitol in Charleston to read a declaration of war to Governor William E. Glasscock. On July 26, miners attacked the town of Mucklow, where the Baldwin-Felts Agents were stationed, leaving at least 12 strikers and four guards dead.

As the strike grew throughout the region, the dispute focused increasingly on the more significant issue of unionization. The strikers focused on recognition of the United Mine Workers of America as their bargaining agent and sought an end to the use of mine guards, blocklisting, and the denial of workers’ rights to free speech and assembly. The mine operators claimed that the UMW was a tool of their competitors in the Midwest and were determined to break the strike and drive the union out.

On September 1, 1912, approximately 5,000 unionized miners from across the Kanawha River crossed the waterway and declared their intent to kill the mine guards and destroy the company operations. Due to this threat, the mining companies deployed additional armed guards and awaited the miners’ attack. Consequently, Governor William E. Glasscock proclaimed martial law on September 2, 1912, and sent 1,200 state troops into the region. Initially, the miners welcomed the soldiers, believing that they would restore peace and protect their rights. However, their views quickly changed when it became clear the militia was there solely to break the strike. In the following days, the troops seized 1,872 high-powered rifles, 556 pistols, six machine guns, 225,000 rounds of ammunition, and 480 blackjacks – as well as large quantities of daggers, bayonets, and brass knuckles.

Confiscating arms and ammunition from both sides lessened tensions, but the strikers were forbidden to assemble and were subjected to fasting and unfair trials in military court. Meanwhile, strikers’ families began to suffer from hunger, cold, and unsanitary conditions in their temporary tent colony at Holly Grove.

On October 15, martial law was lifted, only to be re-imposed on November 15 and lifted on January 10 by Governor Glasscock, with less than two months left in office.

On February 7, 1913, miners again attacked Mucklow, and at least one person was killed. In retaliation, coal operator Quinn Martin, Kanawha Sheriff Bonner Hill, and several deputies attacked the Holly Grove miners’ settlement with the Bull Moose Special that evening. Turning out the train lights, the men fired machine guns and high-powered rifles into the tents and homes of the strikers and their families. After putting 100 machine-gun bullets through the frame house of striker Francis Francesco Estep, he was killed while trying to protect his pregnant wife. Several others were wounded. Estep’s murder enraged the striking miners, and the news of the attack on Holly Grove made national headlines the following day. One reader was so engaged that he sent guns and ammunition to the striking miners. In revenge, the enraged strikers again attacked the mine guards’ camp at Mucklow two days later.

On February 10, 1913, martial law was imposed for the third and final time.

On March 4, Dr. Henry D. Hatfield was sworn in as the new governor and immediately traveled to the area as his first priority. He released some 30 individuals held under martial law, transferred 86-year-old Mother Jones to Charleston for medical treatment, and moved to impose conditions for the strike settlement in April. Strikers had the choice to accept Hatfield’s somewhat favorable terms or be deported from the state. The Paint Creek miners accepted and signed the “Hatfield Contract” on May 1. The Cabin Creek miners continued to resist, with some violence, until the end of July.

The Paint Creek-Cabin Creek Strike of 1912 turned into a 13-month long struggle that lasted through July 1913. Resulting in the death of 12 strikers and 13 company men, the strike counts among the worst conflicts in American labor union history. Fred Stanton, a banker, estimated that the strike and ensuing violence cost $100,000,000.

In no other place and at no other time in U.S. history had martial law been executed on the scale in West Virginia from 1912 to 1913. Without warrants, the soldiers arrested 200 strikers and strike leaders, including Mother Jones, imprisoned them, and tried them before military tribunals for inciting violence even though the civil courts were still in session.

The guards and coal operators faced no consequences for their roles in the violence. Governor Glasscock’s brutal execution of martial law was condemned across the country. Still, little changed in the southern West Virginia coalfields in the following decades.

In fact, it was quite the opposite. The strike was a prelude to subsequent labor-related West Virginia conflicts in the following years, including the Battle of Matewan and the Battle of Blair Mountain.

©Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, November 2021.

Also See:

Hawk’s Nest Strike – First Strike in West Virginia

Mining on the American Frontier

West Virginia Coal Mine Disasters

Sources:

National Park Service

West Virginia Mine Wars Museum

West Virginia Encyclopedia

Wikipedia