The Washita Battlefield National Historic Site, near Cheyenne, Oklahoma, protects and interprets the site of the Battle of Washita. Here once stood the Southern Cheyenne village of Chief Black Kettle that Lieutenant Colonel George Custer attacked on November 27, 1868.

The cultural collision between pioneers and Indians peaked on the Great Plains during the decades before and after the Civil War. U.S. Government policy sought to separate tribes and settlers from each other by establishing an Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Some Plains tribes accepted life on reservations. Others, including the Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Comanche, did not. They continued to hunt and live on traditional lands outside the Indian Territory.

At first, this choice produced little conflict. But following the Civil War, land-hungry settlers began penetrating the plains in increasing numbers, encroaching upon tribal hunting grounds. Indians could no longer retreat beyond the reach of whites, and many chose to defend their freedom and lands rather than submit to reservation life.

Chief Black Kettle

Events leading to the Battle of the Washita began with the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado in 1864. On November 29, troops under the command of Colonel J.M. Chivington attacked and destroyed the Cheyenne camp of Chief Black Kettle and Chief White Antelope on Sand Creek, 40 miles from Fort Lyon, Colorado Territory. Black Kettle’s band flew an American flag and a white flag and considered themselves at peace and under military protection. The terrible slaughter caused a massive public outcry. In response, a federal Peace Commission was created to convert Plains Indians from their nomadic way of life and settle them on reservations.

On the Southern Plains, the work of the Commission culminated in the Medicine Lodge Treaty of October 1867. Under treaty terms, the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Comanche, Kiowa, and Plains Apache were assigned to reservations in the Indian Territory. There they were supposed to receive permanent homes, farms, agricultural implements, and annuities of food, blankets, and clothing. The treaty was doomed to failure. Many tribal officials refused to sign. Some who did sign had no authority to compel their people to comply with such an agreement. War parties, mostly young men violently opposed to reservation life, continued to raid white settlements in Kansas.

Major General Philip H. Sheridan, in command of the Department of the Missouri, adopted a policy that “punishment must follow crime.” In retaliation for the Kansas raids, he planned to mount a winter campaign when Indian horses would be weak and unfit for all but the most limited service. The Indians’ only protection in winter was the isolation afforded by brutal weather.

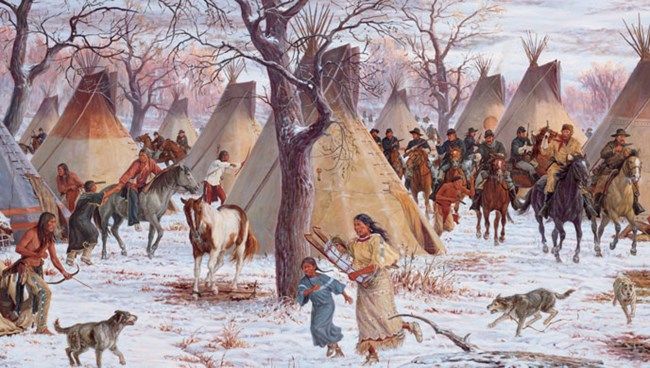

Black Kettle and Arapaho Chief Big Mouth went to Fort Cobb in November 1868 to petition General William B. Hazen for peace and protection. A respected leader of the Southern Cheyenne, Black Kettle had signed the Little Arkansas Treaty in 1865 and the Medicine Lodge Treaty in 1867. Hazen told them that he could not allow them to bring their people to Fort Cobb for protection because only General Sheridan, his field commander, or Lieutenant Colonel George Custer had that authority. Disappointed, the chiefs returned to their people at the winter encampments on the Washita River. Even as Black Kettle and Big Mouth parlayed with General Hazen, the 7th Cavalry established a forward base of operations at Camp Supply, Indian Territory, as part of Sheridan’s winter campaign strategy. Under orders from Sheridan, Custer marched south on November 23, 1868, with about 800 troops traveling through a foot of new snow. After four days of travel, the command reached the Washita Valley shortly after midnight on November 27 and silently took up a position near an Indian encampment their scouts had discovered at a bend in the river.

Black Kettle, who had just returned from Fort Cobb a few days before, had resisted the entreaties of some of his people, including his wife, to move their camp downriver closer to larger encampments of Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Apache who wintered there. He refused to believe that Sheridan would order an attack without first offering an opportunity for peace. Before dawn, the troopers attacked the 51 lodges, killing a number of men, women, and children. Custer reported about 100 killed, though Indian accounts claimed 11 warriors plus 19 women and children died. More than 50 Cheyenne were captured, mainly women and children. Custer’s losses were light: 2 officers and 19 enlisted men were killed. Most of the soldier casualties belonged to Major Joel Elliott’s detachment, whose eastward foray was overrun by Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Kiowa warriors coming to Black Kettle’s aid. Chief Black Kettle and his wife were killed in the attack.

Prisoners from Black Kettles camp, captured by General Custer, Theodore R. Davis,1868. Click for prints & products.

Following Sheridan’s plan to cripple resistance, Custer ordered the slaughter of the Indian pony and mule herd, estimated at more than 800 animals. The lodges of Black Kettle’s people, with all their winter supply of food and clothing, were torched. Realizing now that many more Indians were threatening from the east, Custer feigned an attack toward their downriver camps and then quickly retreated to Camp Supply with his hostages.

The engagement at the Washita might have ended very differently if the larger encampments to the east had been closer to Black Kettle’s camp. As it happened, the impact of losing winter supplies, plus the knowledge that cold weather no longer provided protection from attack, convinced many bands to accept reservation life.

Today the battle site is a National Historic Site run by the National Park Service. The Historic Site preserves the location of the Southern Cheyenne village of Peace Chief Black Kettle. The Visitor’s Center is open daily from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., except for Christmas and New Year’s Day. The overlook and trail are open every day from dawn until dusk. Park Rangers also staff the nearby Black Kettle Museum, which is open from 9:00 to 5:00, Tuesday through Saturday, and closed on state holidays.

The Washita Battlefield National Historic Site is located near the town of Cheyenne, which is situated in western Oklahoma, halfway between Amarillo, Texas, and Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Cheyenne is approximately 30 miles north of I-40 on Hwy 283 and approximately 20 miles east of the Texas border.

Contact Information:

Washita Battlefield National Historic Site

PO Box 890

426 E. Broadway

Cheyenne, Oklahoma 73628

580-497-2742

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated July 2023.

Also See:

Native Americans – First Owners of America

Native American Photo Galleries

Source: National Park Service