Train Robbery

By James H. Kinkead

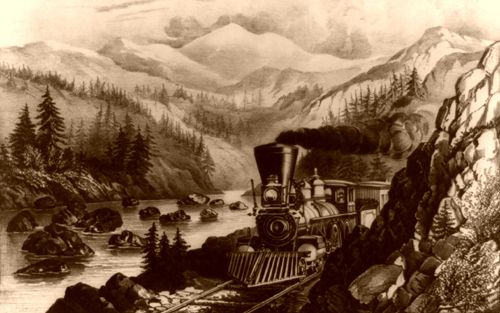

On the morning of November 5, 1870, the news was flashed around the civilized world that the Overland Express train, which left San Francisco, California the previous morning, carrying gold to the miners at Virginia City, Nevada, had been “held up” and robbed near Verdi, a station about ten miles west of Reno, and that over $40,000 had been taken from the Wells-Fargo strongbox by masked heavily armed men. This being the first train robbery on the Pacific Coast, it almost took away the public breath and, for a while, caused great excitement and much newspaper comment on two continents.

Every enemy of law and order was quick to voice praise of the boldness and nerve of the perpetrators of the robbery, and Nevada acquired the dubious credit of being one of the first states in the Union that could produce a set of outlaws daring enough to stop and rob an express train. Immediately, large rewards were offered by the authorities of Washoe County, by the State of Nevada, the Central Pacific Railroad, and the Wells-Fargo Express Company for the apprehension of the robbers, aggregating $30,000. Many men were working on the case in a few hours.

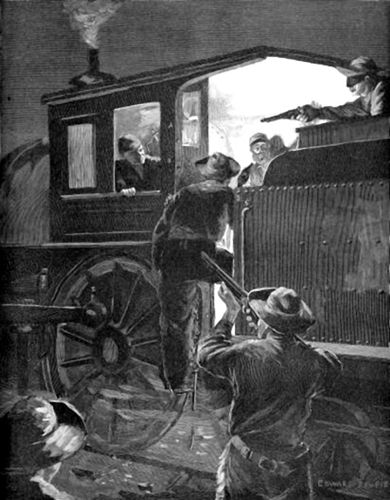

The hold-up occurred in this manner: Just as the train pulled out of the Verdi station, five masked men boarded it. Two of them climbed into the engine’s cab and covered the engineer and the fireman with six shooters. The engine was surrendered at once. Another boarded the front platform of the express car, while two others took possession of the rear platform. After the train had proceeded about half a mile east of Verdi, the men on the engine ordered the engineer to whistle “down brakes.” This was before the days of air brakes, and one short whistle blast brought the brakemen to the platforms, where they began setting the brakes. This was also a signal to the three men on the express car to cut the bell rope and pull the coupling pin at the rear of the car. As soon as this was done, the engineer was ordered to “give her steam,” which he did at once, and when Conductor Marshall went forward to ascertain what had caused the stoppage of the train, he discovered he had lost his engine, mail car, and express car.

The robbers then sped down the grade with this part of the train, leaving the other cars at a standstill. The engineer, realizing what was being done, at first refused to pull out, but the muzzle of a pistol against his temple caused him to obey orders. The fireman was nearly frightened out of his senses and did not have to be told more than once to do anything.

At a point four or five miles west of Reno, the engine came to a halt because of an obstruction on the track, placed there by a confederate of the robbers. They had figured that the engineer might run past the place designated for the hold-up or play them some trick by opening the throttle and jumping from the engine.

After the engine was stopped, there was a knock at the door of the express car, and Frank Minchell, the messenger, called out, “Who’s there”? and the reply was, “Marshall.” The messenger then opened the door and, instead of seeing Conductor Marshall as he expected, was confronted by the muzzle of a double-barreled sawed-off shotgun. He was entirely taken by surprise and surrendered without any fight. After telling him to sit down in the corner of the car and keep quiet, the robbers threw the Wells-Fargo sacks of gold, containing $41,000, through the side door of the car into the brush, thanked the messenger for giving them so little trouble, adding that they were glad they did not have to kill him, shouldered their booty and disappeared into the darkness.

Meanwhile, Conductor Marshall allowed his headless passenger train to drop slowly down the grade, anticipating the danger of an unknown character but boldly facing it. When his train arrived at the robbery scene, he found that the work of the robbers was finished, and the engineer and fireman were busy removing the obstructions from the track. The train was then “made up” and continued, reaching Reno thirty minutes after midnight, only thirty minutes late.

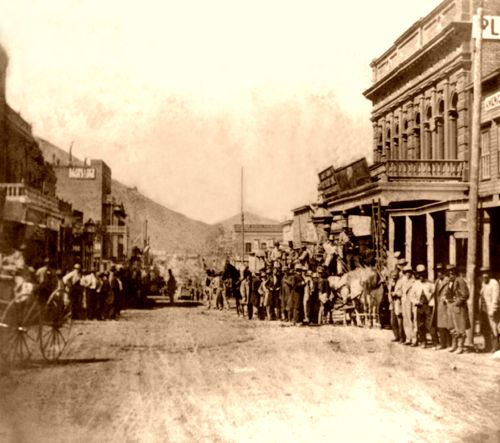

Washoe City was then the county seat of Washoe County, and the first news of the robbery reached the Sheriff’s office at 8 a.m. The message came from C. C. Pendergast, Wells-Fargo agent at Virginia City, and read: “Train robbed between Truckee and Verdi; robbers went south.”

The Sheriff, Charley Pegg, and his undersheriff immediately saddled up and struck for the mountains by a shortcut, assuming that the robbers would take the Truckee route between Truckee, Carson City, and Virginia City. Thus, they expected to head off the robbers. After striking the trail, the officers followed it north for a few miles and then returned to Washoe City, for they were convinced that no one had passed over the trail since a lightfall of snow a week before.

The message from Pendergast proved to be misleading since the robbery occurred below Verdi instead of above it, and the officers lost the first day. However, they were just in time to catch Dwyer’s stage to Reno at 9 o’clock that night.

The Deputy Sheriff took passage on this stage and, upon reaching Reno, learned that the Wells Fargo detectives and some of the railroad and Reno officials, together with a posse of citizens from Reno, had been out all day on a “sure clue” which afterward proved to be a false one.

Early the next morning, the Washoe County officer went to the robbery scene with a fresh horse and discovered one footprint that was easily distinguished from the others after carefully examining the ground. It was made of a boot having a very small heel, such as the dudes and the gamblers wore in those days and our wives and daughters wear now. No laboring man or railroad employee ever wore that boot, and it was too soon after the robbery for the curious to have visited the ground. Hence, the officer in charge of the party knew that if he could find that track and follow it after it left the robbery scene, he would be sure to land at least one of the robbers.

After examining the ground up and down the track, he finally reached a point about a mile west where the small heel print and two larger ones left the track and led north. The robbers had evidently walked for quite a distance on the railroad ties to prevent being trailed. The officer followed these tracks up Dog Valley Creek and over Dog Valley Hill, where it was easy trailing in the snow, into Sardine Valley, California. At the Sardine Valley House, he gained valuable information. Three strangers had lodged there the night before. Two had left early in the morning, and the other one was still in his room when a party of hunters from Truckee, led by James Burke, arrived at the house. They were well supplied with shotguns, and the stranger in the house at once mistook them for officers. Running out of the back door, he hid in the barn. In the meantime, a man had arrived from Truckee and reported the train robbery. The lady of the house then related to the hunters the particulars of the three men coming to her house late the previous evening. She said that one of the men was still there and seemed nervous and worn out. Although not an officer, James Burke decided to arrest the man, who proved to be Gilchrist, a Virginia City miner who, up to that time, had borne a good reputation.

Undoubtedly, this was his first venture in the “hold-up” business. He was taken in Truckee by the hunters.

The landlady of the Sardine Valley House gave the Washoe County officer a very good description of the other two men. She described them accurately and went into detail about their clothing. Among other things, she said that one of them wore “gambler’s boots, and from her description of the other man, the officer rightly guessed that he was John Squiers, an old stage robber whom the officers of Storey County had been trying to land for years.

He was heading for Sierra Valley, where his brother Joe, an honest blacksmith, resided and where he thought he could rest in safety until the excitement caused by the robbery subsided. After feeding and resting his horse, which had been on the go since daylight, the officer, in about an hour, took up the hunt for the other men.

It was now 10 p.m., and the snow was falling fast. The officer was out of his jurisdiction and unacquainted with that section of the country. He, therefore, found it necessary to procure a guide to put him on the right road to Sierra Valley; otherwise, he might land at Webber Lake or Downieville, many miles away. Several men were at the Sardine Valley House, but none had “lost any robbers,” and they refused to act as guides. A boy, however, volunteered for ten dollars to go with the officer as far as Webber Lake Junction and put him on the right trail to Loyalton in Sierra Valley, but with the distinct understanding that, in case the robbers were encountered, the boy was to turn back and let the officer fight it out alone. However, nothing of the kind occurred, and at about midnight, they arrived at the little town of Loyalton in Sierra Valley, California.

Arousing the landlord of the only hotel in the village, the officer made himself known and asked if there were any strange guests in the house. The landlord replied that he had one and described him, but the description did not fit the man sought. The officer, however, thought it best to look at the man and asked the landlord to show him to the room.

By this time, either from the cold or the thought of a desperado being in his house, the landlord’s teeth were chattering, and he declined to go, but giving the officer a candle, he told him the man was in room 14. The hotel had just been built and had not been painted, and on account of the damp weather, the doors were swollen, and the door of room 14 could not be shut tight enough to lock. For this reason, the occupant had placed a chair under the knob on the inside of the room and had gone to bed, probably feeling quite secure against intruders.

The officer after reaching the second story of the hotel readily found room 14 and noticing that the door stood partly open, he gently pushed it until the chair moved sufficiently to enable him to get his arm through the crack and remove the obstruction.

This he did without awakening the sleeper, and the first object that attracted his attention after entering the room was a boot, lying on the floor, with the little heel that had made the tracks he had followed for so many miles and that afterward cut such an important figure in the trial of the robbers.

After entering the room, the officer found his man sleeping like a log and first proceeded to remove a six-shooter from under his pillow without disturbing his slumbers and also went through his clothes in search of further evidence to connect him with the robbery. Enough was found to assist in the later conviction of the men. When the officer finally aroused him to place him under arrest, he bounded from his bed and landed in the center of the room like a wild animal. Rushing back to the bed, he reached for his gun but found it missing while the officer, covering him with a Henry rifle, commanded him to get on his clothes, which he did without any further conversation. He then was marched on ahead of the officer and down the street to a saloon, where he was bound and placed under guard while the officer went in search of the other man. The man arrested in the hotel proved to be Parsons, a gambler from Virginia City.

On his way toward Sierraville, California, the officer found John Squiers at his brother’s house. The officer knew Squiers and believed he would have trouble taking him “in the open.” Arriving at Joe’s house before daylight and before anyone was astir, he placed himself in the rear of the house, in the willows, and waited. Presently, a man came through the kitchen and left the door ajar, proceeding to the barn with a pail on his arm, evidently about to do the morning milking. The officer slipped into the house through the kitchen and into four separate rooms where men were sleeping before he found the man he was looking for. Here again, the officer had the luck to disarm the man without waking him, and gathering up his clothes and boots, he aroused him and, at the muzzle of the rifle, drove him out of the house and then allowed him to put on his clothes.

While this was being done, the man who had entered the barn came out, and Squiers immediately yelled at him that he was being robbed. The household was soon in a commotion, and the crowd grew noisy.

After securing the prisoner, the officer made a speech to the crowd explaining that he was an officer in the discharge of duty and had arrested Squiers on suspicion of complicity in the train robbery. Squiers, however, knowing the officer, claimed that the latter had no right to make an arrest in California.

The crowd concurred with this view, especially as Joe Squiers, the brother of the captured man, was a respectable citizen of the valley, where he had many friends. It began to look bad for the officer. But a team was being hitched up, and when it was ready and standing in the rear of the saloon, the prisoner was rushed into it; the officer succeeded in getting away from the crowd and eventually landed both Squiers and the other prisoner in the Truckee jail where Gilchrist already was confined.

On arriving at Truckee, the officer telegraphed to H. G. Blasdel, the Governor of Nevada, for a requisition on Governor Haight of California.

On the following day, this arrived, and the prisoners were taken across the line into Nevada over the same railroad whose train they had assisted in holding up. While awaiting the requisition, Gilchrist had been kept separate from the other men and had been “sweated,” with the result that he made a complete statement before a Notary Public, in which he gave the names of all the parties connected with the robbery.

A telegram was immediately sent to Wells Fargo in Virginia City, directing the arrest of “Jack” Davis, and another was sent to Reno, calling for the arrest of John Chapman, Sol Jones, Chat Roberts, and Cockerell. Davis was arrested in Virginia City by Chief of Police George Downey and Constable Ben Lackey, and Jones, Roberts, and Cockerell were taken in Long Valley by a posse headed by Chief Burke of Sacramento and Louis Dean of Reno. Chapman, who was in San Francisco on the day of the robbery, came up to Reno on the following day and was arrested by Deputy Sheriff Edwards. This completed the arrests. The entire gang had been rounded up in less than four days after the robbery occurred, and most of the money was recovered. Gilchrist showed the officers where the money was cached, saying that it was the intention to let it remain there until the excitement of the robbery had subsided when it was to have been dug up and divided.

A grand jury was immediately called by Judge C. N. Harris of the District Court of Washoe County; indictments quickly followed, and the men were put on trial early in December. They were convicted, and, except Gilchrist and Roberts, they were all landed in the Nevada State Prison on Christmas Day of the same year.

The trial was a memorable one in the criminal annals of Nevada. Judge C. N. Harris presided. W. M. Boardman was District Attorney, and Thomas H. Williams appeared for Wells, Fargo & Co. Attorney General Robert M. Clarke, a brother-in-law of the Washoe County officer, and who later successfully prosecuted the United States mint thieves at Carson City, represented the State.

The celebrated criminal lawyer, “Jim” Croffroth of California, appeared for the Central Pacific Railroad Company. The prisoners were ably defended. Judge Thomas E. Haydon of Reno appeared as special counsel for Chapman, and the others retained William Webster of Washoe City, who was later the editor of the Reno Journal.

It was a great legal battle, and the principal fight was over Chapman. He was in San Francisco on the day of the robbery, and his attorney claimed that the State of Nevada had no jurisdiction in his case. To bring him into the jurisdiction of this court, it was necessary to prove a conspiracy and that it was hatched in Nevada.

This was shown to be the case by the confessions of Gilchrist and Roberts, who were promised immunity if they would tell the whole story. Other sources also corroborated their evidence. Gilchrist and Roberts testified that the job was put up at Chat Roberts’ ranch in Nevada, Chapman being present. At the time, it was arranged that Chapman was to go to San Francisco and watch the shipment from Wells, Fargo & Co’s office and to send a cipher message to Sol Jones at Reno, who would then notify the other men who were to await the coming of the message in an old tunnel in the Peavine Mountains north of Reno.

Sol Jones also testified and explained the meaning of the cipher message, which read: “Send me sixty dollars tonight without fail,” and was signed “J. Enrique.” Jones said it meant: “Be on hand tonight without fail.” Jones had been promised the lowest sentence under the law to testify on behalf of the State. He did this and was later sentenced to five years in state prison.

Chapman denied the sending of the telegram. But the Western Union operator in San Francisco brought the original message into court and swore positively that Chapman was the man who delivered it to him early on the morning of November 4. However, his attorney maintained his contention of the lack of jurisdiction and produced authorities to support his argument. Among others was one from California, wherein the defendants were tried in one county in a specific robbery case. In contrast, the robbery was committed in another, and the Supreme Court of California granted a new trial for lack of jurisdiction.

But, General Clarke, in a remarkable argument, successfully combated the contention of Chapman’s attorney. On appeal, the Supreme Court also held that the conspiracy was concocted in Nevada, Chapman being present, that the sending of the telegram from San Francisco was a part of the same unlawful act that culminated in the train robbery in the State of Nevada, and that Chapman in law was as securely within the jurisdiction of the court as any other of the defendants, and that if he could not be tried in Nevada the law certainly could not reach him in California, since the sending of the message from California did not constitute a crime against that State.

The sentence of the convicted robbers ranged from five to 23 years, with Jones getting the lightest sentence and Chapman and Squiers the heaviest.

The sending of these men to the penitentiary nearly wiped out the stage-robbing industry in Nevada, for it imprisoned the men who, for years, had been stopping the Wells Fargo stages. The Washoe and Storey Counties officers had long been convinced that “Jack” Davis and John Squiers had been in every hold-up. Still, their work had been so smooth that whenever they had been brought before a jury, they had succeeded in establishing “reasonable doubt.” Chapman was known to be a ringleader of the robber gang. A short time before, Wells Fargo & Co., to protect their stages, had put on an extra guard in addition to the regular messenger. Guards also traveled behind the coaches on horseback. The gang soon concluded that there was no more easy money to be had out of the stages, so they were forced to change their base of operations. Chapman and Squiers conceived the idea of holding up a railroad train. It was a remarkably well-concocted plan, and all the details were worked out to perfection, the only mistake being in the selection of the men. They did not need Gilchrist and Jones, who were novices in the business and gave up everything they knew under pressure of the sweat-box.

The convicted men all served their terms in the penitentiary except Davis. A few years after the incarceration, there was a break at the Nevada State Prison, in which several guards were killed and Warden Denver tied up. The convicts had complete control of the place, but Davis refused to pass through the open gates and rendered some assistance to the officers. For this, he was pardoned, having served five years. Within a year after his discharge, he attempted to hold up a stage in White Pine County, but Eugene Blair, a shotgun messenger, got the drop on him and riddled his chest with buckshot, making a truly “good Indian” of him.

Of the others connected with the robbery, nothing is known of their lives after their discharge, except Squiers, who next turned up in California, where he was convicted of jury fixing and served five years in San Quentin. He was a spectator at the Gans-Nelson fight in Goldfield a few years ago. He is now a gray-haired, frail old man who, if still living, is too old to do much damage in this world.

Of the officers who took a prominent part in the arrest and conviction of the train robbers, all are dead, save the one who followed the small footprints through the mountains until they led him to the lair of the robbers. He also collected most of the evidence used at the trial and, for these services, received most of the large reward.

By James Kinkead, Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2024.

About the Author: Not a professional writer, James H. Kinkead, however, created this hand-written document that was found after his death. An Under Sheriff of Washoe County, Nevada, Kinkead, arrested two train robbers. His narrative of the First Train Robbery On The Pacific Coast first appeared in the Third Biennial Report of the Nevada Historical Society, 1913, Carson City, Nevada. The officer who arrested the robbers, and of whom C. C. Goodwin wrote: “He believed Nevada had everything that was needed for a man who had brains and physical strength and the pluck behind the two to carry through his plans.” As it appears here, the article is not verbatim, as it has been edited for clarity and ease for the modern reader.

Also See: