The mystery and legend of renegade Indian, Queho (pronounced Key-Ho), continues to be debated today as to whether he was a scoundrel or a scapegoat. Was the Southern Nevada Indian a true outlaw killer or was he merely blamed by law officers for an abundance of unsolved crimes?

Thought to have been born around 1880 at Cottonwood Island near the town of Nelson, Nevada, Queho’s Cocopah mother died shortly after giving birth. Though the identity of his father remains a mystery, various theories have been presented including a Paiute brave from a neighboring tribe, a white soldier from Fort Mohave, or a Mexican miner. Though the answer to this question will never be known, Queho was an outcast from the start due to his “shameful” mixed blood. Adding to this, the boy was born with a club foot, which further caused the local tribes to reject him.

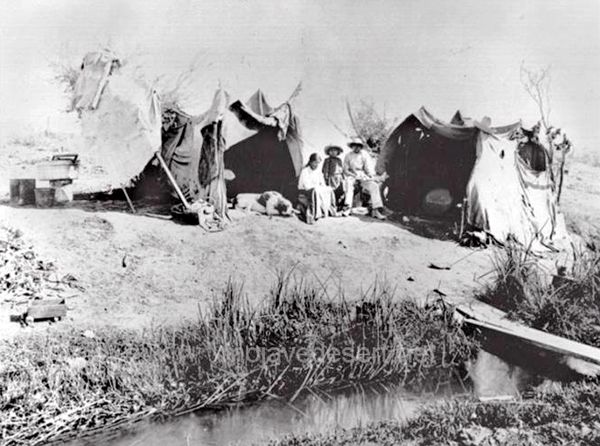

Raised on a reservation in Las Vegas, he worked from an early age as a ranch laborer and wood gatherer in several of the nearby mining camps. Always known to be sullen, moody, and quick-tempered, it came as no surprise when he began to have troubles with the law.

Some stories, though unconfirmed, tell of him being involved in the death of another Indian in 1897, but newspaper accounts of his exploits do not begin until November 1910. The first report tells of Queho being the main suspect in a slaying of another Indian during a brawl on the Las Vegas reservation. Allegedly, he and the other man, named Harry Bismark, were drinking when the dispute began. Queho went on the run and according to some accounts, murdered two Paiute Indians when he stole their horses in his escape.

On his flight, he stopped for supplies in Las Vegas and was confronted by a shopkeeper named Hy Von, which resulted in Queho breaking both the man’s arms and fracturing his skull with a pick handle. Fleeing south to Nelson, he took shelter in Eldorado Canyon.

Before long, word came from Searchlight that a Queho had beaten to death a woodcutter named J.M. Woodworth. According to the tale, he had beaten the man with a piece of timber after Woodworth refused to pay him after having helped him cutting timber.

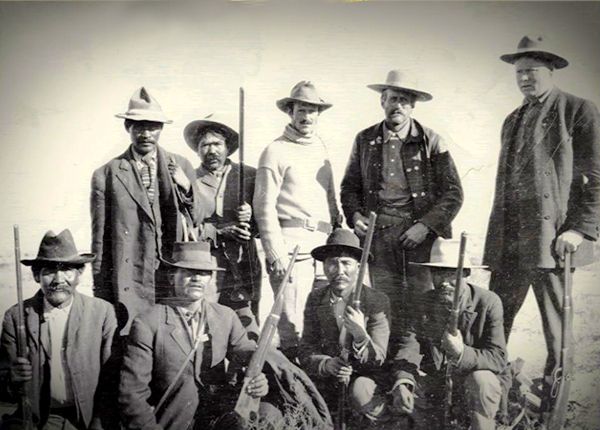

Deputy Sheriff Howe formed a posse and group first went to the scene of Woodworth’s killing where they found a distinctive print left by Queho’s clubfoot. From there, they tracked the fugitive to Eldorado Canyon where they led to the Gold Bug mine. There, they found the body of the watchman, L.W. “Doc” Gilbert. Shot in the back, Gilbert’s special deputy badge No. 896, had been stolen. Continuing to track Queho to the Colorado River, they lost the trail. Though the lawmen had searched for Queho over a 200-mile area ranging from Crescent to Nipton, they found nothing but the trace footprints. Having thought that Queho would be easy to track and capture due to his clubfoot, they couldn’t have been more wrong. After some time, they finally gave up the chase.

However, Nevada State Police Sergeant Newgard soon picked up the search along with several Indian trackers and two experienced hunters. Though they also found signs of Queho’s presence, they too finally gave up the search when they ran short of supplies. The frustrated and exhausted lawmen returned to Las Vegas empty-handed in February 1911.

Over the next several years, the sightings of Queho continued and his legend began to grow. Up and down the length of the Colorado River, miners and settlers told of missing cattle, unexplained thefts, and mysterious murders. All were attributed to the phantom renegade, which served as a constant source of embarrassment to the local lawmen.

In 1913, local newspapers attributed the death of a 100-year-old blind Indian known as Canyon Charlie to Queho. Allegedly, Charlie’s few provisions were gone, which included little more than food, prompting everyone to believe that Queho would kill for almost anything. However, there were others that disputed the murder as being Queho’s responsibility, as the old Indian was known to be the fugitive’s friend and confidant.

A few months later when two more miners working claims at Jenny Springs were found shot in the back and their provisions were stolen, these murders, too, were blamed on the illustrious outlaw. An Indian woman found dead a short time later was also blamed on the renegade.

The hysteria continued to grow until rewards reaching $2,000 were offered for his capture, “Dead or Alive.” The Searchlight Bulletin was quick to remind its readers of the reward while screaming, “A good Indian is a dead Indian.”

Though the furor died down for several years, area settlers continued to worry anytime someone went missing for even an hour or two. Queho became the stuff of legends and the bogeyman to scare children into behaving.

In 1919, the murderous tales would begin again when two prospectors named William Hancock and Eather Taylor were found dead upstream from Eldorado Canyon. Both had been shot in the back and Taylor’s head had been smashed in with an ax handle. With their supplies missing and Queho’s footprints allegedly being found at the site, he was immediately the prime suspect.

About a week later on January 21, 1919, Maude Douglas, the wife of an Eldorado Canyon miner, was awakened in the night by a commotion in the larder at the rear of the cabin. When her husband heard a shotgun blast, he found her shot in the chest and surrounded by canned goods. When authorities arrived at the cabin near the Techatticup Mine, they pronounced it to have been yet another crime committed by Queho as they allegedly found his footprints around the cabin. Though a four-year-old boy in Maude’s care said that the woman had been killed by her husband, no one listened, immediately resuming the chase for the elusive Indian renegade once again.

The reward for Queho’s capture was increased to $3,000 and southern Nevada Sheriff Sam Gay ordered Deputy Frank Wait to round up a posse and hire the best trackers to once and for all kill or capture Queho. Though they tracked the outlaw north to Las Vegas Wash and on into the Muddy Mountains, they soon lost his trail. Gathering up yet more men, Wait split the group into two parties who continued the search. The manhunt lasted almost two months, despite freezing rain and snow. Though they didn’t find Queho, the lawmen did find the skeletons of two miners who had disappeared several years before. Though there was no proof whatsoever, Queho took the blame for these murders as well.

As sightings of Queho continued over the next several years, Undersheriff Frank Wait would resume his search periodically in the area where Boulder Dam would later be built to as far south as Searchlight. But when no further murders were committed, interest in the elusive Indian faded.

The last time that the renegade was reportedly seen was when he was spotted by a Las Vegas policeman walking down Fremont Street in February of 1930. The officer immediately summoned reinforcements, but by the time they arrived, Queho was gone once again.

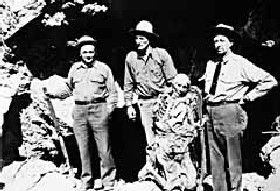

Posse that recovered Queho’s remains stands at the mouth of his cave hideout. From left, Clarke Kenyon, Frank Wait, and Art Schroeder. Photo courtesy UNLV Special Collections

As the legend was finally beginning to die, three prospectors by the names of Charles Kenyon and brothers, Art and Schroder, found the remains of a dead Indian on February 18, 1940. High in a cave on the side of Black Canyon, the mummified body was found along with a Winchester 30/30 rifle, clothing, cooking utensils, tools, and a “special Deputy badge, No.896”.

Frank Wait, then Chief of police for Las Vegas, and original member of the posse in 1910 rushed to the scene and positively identified the remains as belonging to Queho. A few days later on February 21, 1940, he headlines in the Las Vegas Review-Journal read “Body of Indian Found.”

Queho’s remains were taken to Palm Funeral Home in Las Vegas and Charles Kenyon, who had first found the body, demanded the reward. However, when the rewards offered more than a decade earlier were ignored, Kenyon demanded that the body be turned over to him.

When he threatened to sell it to the Las Vegas Elks Club for exhibition purposes, a court order was issued to prevent him from doing so. In the meantime, several Indians came forward claiming to be Queho’s heirs. As the corpse lay in storage at the funeral home, charges were accumulating and the facility was demanding that the body be moved and the bill paid. Suddenly Kenyon and those claiming to be heirs “disappeared” and the judge ruled that the funeral home had all rights to the body. All this haggling had taken three years and the funeral home issued an ultimatum that if the body wasn’t retrieved and the charges paid, it would cremate the corpse and scatter the ashes over the desert.

Queho’s mummified remains were found surrounded by all his possessions. Photo courtesy UNLV Special Collections

Queho’s old nemesis, Frank Wait paid the bill and gave the remains and artifacts to the Las Vegas Elks Club, who produced what was then the city’s biggest public celebration, “Helldorado”. The club then built a glassed-in case and recreated a “cave” to exhibit the body and artifacts at Helldorado Village in Las Vegas. The Indian’s remains stayed on public display until the early 1950s and, on at least one occasion, even rode in one of the famous Las Vegas Helldorado parades.

When the Elks Club no longer wanted responsibility for Queho’s remains that passed through several private hands before landing at the Museum of Natural History at the University of Nevada, where they remained until the mid-1970s. Finally, a retired Las Vegas attorney by the name of Roland H. Wiley secured the remains from the museum, and on November 6, 1975, Queho was finally laid to rest. In a small ceremony on Wiley’s Pahrump Valley ranch, the ceremony was attended by Frank Wait, who told the local press he was relieved that his old adversary had finally been given a proper burial.

During his lifetime, Queho was credited with the deaths of 23 people, was declared as Nevada’s “Public Enemy No. 1,” and the state’s first mass murderer. While many believe that the Indian was little more than a brutish killer, others see him as an abused man who was hounded his entire life and blamed for dozens of atrocities that he did not commit. The truth remains a mystery.

© Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated November 2019.

Also See:

Eldorado Canyon – Lawlessness on the Colorado River

Hell Dogs of Eldorado Canyon – Ghostly Canine Apparitions