Just two miles north of the city of Taos, New Mexico, stands the centuries-old Taos Pueblo, one of the longest continually inhabited communities in the United States. Archaeologists have found evidence that the Taos Valley has been inhabited as far back as 3,000 B.C. and prehistoric ruins dating from 900 A.D. can be seen throughout the area. However, the Taos Pueblo is thought to have been built between 1000 and 1450 A.D. and appears today much as it did a millennium ago, linking today’s Native Americans with those early inhabitants of years ago.

Built by the Northern Tiwa tribe, the pueblo is made entirely of adobe – a combination of earth mixed with straw and water, and then either poured into forms or made into sun-dried bricks to build walls that are often several feet thick.

The roofs of the buildings, some of which are as many as five stories high, are built wood poles, which are placed side-by-side and covered with pack dirt. Support for the rooms and buildings comes from large timbers, which were hauled down from the mountain forests which surround the pueblo. Throughout the years, the exterior has been maintained by continuously re-plastering with thick layers of mud. Though today, the pueblo displays both doors and windows, this has not always been the case. Originally, the buildings had no doors or windows and entry could be gained only from the top of the buildings.

Running through the center of the community is a small stream called Red Willow Creek, which begins high in the Sangre de Cristo Range, at the tribe’s sacred Blue Lake and flows quietly through the community, before becoming a whitewater river and eventually joining the Rio Grande. The stream has long served as the primary source of water for drinking, cooking, bathing, and religious activities for the pueblo. Due to its swiftness, the river never completely freezes in the winter, although it does form a heavy layer of ice, which can easily be broken to obtain the freshwater beneath.

The first Europeans to see the pueblo were Captain Hernando de Alvarado and a detachment of some 20 soldiers who had been sent by Francisco Vasquez de Coronado to explore what is now northeast New Mexico in 1540. The name “Taos” was borrowed from the Spanish word “təo” meaning “village.”

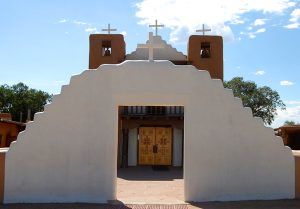

Don Juan de Oñate Salazar, an explorer and colonial governor of New Spain (present-day Mexico), came to Taos in July 1598 and in September, he assigned Fray Francisco de Zamora to serve the Taos and Picuris Pueblos. In about 1619 the first Spanish-Franciscan mission was built by priests with Indian labor and called San Geronimo de Taos.

The long-established trading networks at the Taos Pueblo, its mission, and abundant water, timber, and game, soon attracted early Spanish settlers to the area. However, these newcomers also created conflict with the Taos Pueblo due to their authoritarian ways and forced religion, which eventually resulted in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680.

Planned in months of secret meetings centered at the Taos Pueblo, a coordinated attack was made by several pueblo communities in August 1680, assaulting several Spanish settlements. With more than 8,000 Pueblo warriors, the Indians killed 21 Franciscan friars, more than 400 Spaniards, and drove some 1,000 settlers out of the region. Unfortunately, during the uprising, the San Geronimo church at the pueblo was also destroyed.

However, 12 years later, in 1692, Don Diego de Vargas made a successful military reconquest and re-colonized the province. In 1694 De Vargas raided the Taos Pueblo when it refused to provide corn for his starving settlers in Santa Fe. The Taos Pueblo revolted again in 1696, and De Vargas came for the third time to put down the rebellion. In 1706, the San Geronimo Mission was rebuilt.

Finally, Taos and other Rio Grande pueblos settled down and became allies with Spain and later of Mexico, when it won its independence in 1821.

The settlement of Taos, which grew up around the pueblo, soon grew in importance as a trading center and by the early 1800s, was called home to a number of famous mountain men, including Kit Carson, Smith Simpson, and Ceran St. Vrain. But, the pueblo would see conflict again in the Mexican-American War, when U.S. General Stephen Kearney and his U.S. troops occupied the province of New Mexico in 1846.

A “new” San Geronimo Mission was built in 1850. The youngest of the structures in the pueblo, it still services parishioners today, Kathy Weiser-Alexander.

The following year, Taos rebelled against the new wave of invaders and killed the newly appointed Governor Charles Bent in his Taos home. U.S. troops soon retaliated, killing some 150 Indians, destroying the San Geronimo Mission, and afterward, executing 16 Indians for their part in the revolt. The ruins of the mission can still be seen today to the northwest of the two main pueblo blocks. A new church was built in 1850 within the walls of the original pueblo.

The Tiwa people and the Taos Pueblo moved on into the future with the rest of the American West, but continue to maintain many of the native traditions, cultures, and customs, especially within the pueblo walls. Though the pueblo buildings have been updated to include doors, windows, it continues to look very much as it did throughout its long history and does not allow modern utilities such as plumbing and electricity. The pueblo on the north side of the river, called Hlaauma, is one of the most photographed buildings in the Western Hemisphere and is the largest multi-storied Pueblo structure still standing. The homes in the building usually consist of two rooms, one for living and sleeping, and the other for cooking and dining.

About 150 tribe members live within the pueblo full time, while some 1,800 more live on other areas of the 99,000-acre pueblo lands. The village is governed by a Tribal Governor and War Chief and their staff, which are appointed annually by the Tribal Council, a group of some 30 male tribal elders.

The Governor and his staff deal with civil and business issues within the village and relations with the non-Indian world. The War Chief and staff deal with the protection of the tribal lands, resources, and wildlife outside the pueblo walls. All adults who live on tribal lands are expected to provide their services for community duties when needed.

The tribe holds its culture and traditions very close to their hearts and their oral traditions and native language are unwritten and unrecorded. Much of their history, rituals, and traditions are considered sacred and therefore off-limits to non-tribal members. However, visitors to the pueblo can still marvel at the architecture and hospitality provided by the pueblo.

Tourism, native crafts, and food concessions are an important part of the pueblo economy and numerous vendors can be found within the pueblo, displaying pottery, silver jewelry, leather works, bread, and more. These shops are open to the public, but unless a door clearly states it is a “shop,” no entrance should be made to any building, as these are private homes.

Drying racks have been used for centuries for drying meat, vegetables and animal hides for clothing. Adobe ovens, called hornos, are still used by women for baking breads, pastries, wild game, and vegetables.

One of the main highlights of the pueblo is the San Geronimo Church built in 1850. Though it is one of the “youngest” buildings in the village, it provides a wonderful example of mission architecture, as well as an interesting look at how the tribe incorporated their values into the Catholic religion. The church, which is listed as a National Historic Landmark, continues to serve as an active church and requests for “no photography” inside should be respected.

The remains of the first San Geronimo Church, destroyed in 1847, can also be seen sitting inside the cemetery. However, the cemetery itself should not be entered by visitors.

One of the main events of the summer is the annual Taos Pueblo Pow wow, a gathering of spiritual leaders and tribal members, that features costumed dancers, singers, and other ceremonies, as well as a wide array of vendors and artists. Other events are also held throughout the year. The tribe also owns and operates the Taos Mountain Casino just south of the pueblo.

Taos Pueblo is open daily to the public year-round from 8 am to 4:30 pm, with the exception of special ceremonies, tribal funerals, and a ten-week period during the late winter/early spring. Fees are charged for admission and camera use.

The Taos Pueblo requests that the following rules/etiquette be followed when visiting:

- Please report, and pay the appropriate fee for, each camera that is carried into the pueblo area.

- Please respect the “restricted area” signs as they protect the privacy of residents and the sites of native religious practices.

- Do not enter doors that are not clearly marked as curio shops. Each home is privately owned and occupied by a family and is not a museum display to be inspected with curiosity.

- Please do not photograph members of the tribe without first asking permission. When permission is granted, it is customary to tip the individual.

- Absolutely no photography is allowed in San Geronimo Chapel or anywhere on Feast Days.

- Do not enter the walls surrounding the ruins of the old church and cemetery.

- Do not wade in the river — it is the sole source of drinking water.

- Do not climb onto any structures or ladders.

More Information:

Taos Pueblo

Taos, New Mexico

575-758-1028

© Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated August 2021.

See our Taos Photo Gallery HERE

Also See:

Ancient & Modern Pueblos – Oldest Cites in the U.S.

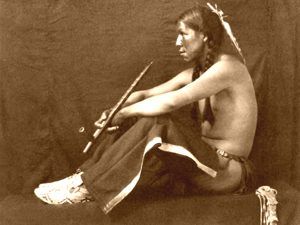

The Tiwa Tribe – Fighting the Spanish

Pueblo Indians – Oldest Culture in the U.S.

Pueblo and Reservation Etiquette

The Mountain Song of Taos – or, The Taos Hum

Taos- Art, Architecture & History