Shakespeare, New Mexico, a ghost town in Hidalgo County in the southwest portion of the state, has gone by a number of names throughout the years. Today, it is part of a privately owned ranch that is sometimes open to tourists. The entire community was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.

Some sources say that the site started as a rest stop called Mexican Spring due to a small but reliable spring located in an arroyo west of the present-day townsite. In about 1856 a building was constructed here by the Army, evidently to serve as a relay station on the Army Mail line between Fort Thorn on the Rio Grande and Fort Buchanan, Arizona. During the Civil War, more people used the spring as soldiers made their way back and forth across the southwest. During this time, one or two more buildings were built at Mexican Spring by the soldiers – the largest one called “old stone fort.” After the Civil War, the site was renamed Grant after General U. S. Grant.

Around 1870, the area that would eventually become Shakespeare had attracted a number of prospectors always on the look-out for mineral deposits. When a couple of them found rich silver ore, they contacted San Francisco businessman and financier, William Ralston, co-founder of the Bank Of California six years earlier. When the prospectors were successful in gaining Ralston’s financial support to develop the mines, the resulting settlement was named Ralston in his honor.

Soon, the New Mexico Mining Company was digging for ore and a new town was laid out, filling with tents and about 200 people. In no time; however; the town boomed when newspapers as far away as San Diego and San Francisco, told the news of the rich silver finds. More miners flocked to the area, that some say, soon sported some 3,000 people.

Though the New Mexico Mining Company found a few isolated pockets of silver ore, William Ralston’s credibility was quickly waning due to his involvement in several dicey scams, one of which was the Great Diamond Hoax of 1871. His stock dropped dramatically and people began to leave the newly formed camp. By 1873, there were only a few people left in the boomtown. William Ralston, meantime, would see his Bank of California collapsed during the depression of 1875, leaving him in financial ruin. That same year, on August 27th, he reportedly went for a swim in the San Francisco Bay and drowned.

In 1879, though the town of Ralston was virtually non-existent, another investor, Colonel Boyle of St. Louis, Missouri, staked a number of claims under the name of the Shakespeare Mining Company and renamed the settlement, Shakespeare. Mining was in full force again with the principal mines being Boyle’s Shakespeare Gold and Silver Mining and Milling Company, as well as the Atwood, Miners Chest, and others. Colonel Boyle also bought an adobe building which he turned into the Stratford Hotel. The town began to grow again, this time with more adobe buildings. In the 1883 publication Congressional Series of the United States Public Documents, Volume 2113, Shakespeare is described as follows:

“Like most towns which are built in a country infested with Indians, as this has been in the not remote past, Shakespeare is built of adobe, as affording best means of defense as well as furnishing the greatest amount of comfort attainable in a frontier residence.

“It is not a large town, although it would seem to have elements about it to have made it so ere this. The Atwood mine.. is on its outskirts; the Superior.. is but a mile away; the Jerry Boyle, an immense copper vein, immediately adjoins the Atwood; the Miner’s Chest, less than 2 miles away, and upwards of a hundred other good claims in more or less advanced stages of development within a radius of less than 3 miles, is enough to furnish employment for thousands of miners. Not only in the number of claims but in the great diversity of ores, generally carrying both silver and gold, although other veins show excellent galena ores carrying largely of silver.”

Though the town was typical of the time with rowdy miners and lawlessness, it never gained the reputation of other mining towns of the time, such as the more decadent mining camps of Leadville, Colorado, and Deadwood, South Dakota.

In fact, men began to bring in their families and settle down; however, the town never settled so much as to ever get a school, a church, or a newspaper.

“Law” was generally handled by the citizens of the community, even though the settlement was overseen by a County Deputy Sheriff as early as 1870. Some offenders were even hanged by the timbers of the Grant House dining room.

On one occasion, a well-known outlaw by the name of Sandy King was making his home in Shakespeare and when he got into an argument with a storekeeper and shot off his index finger, he was quickly taken to jail by Deputy Sheriff Dan Tucker.

At about the same time, King’s friend, William Tattenbaum, better known as “Russian Bill“, was tracked down on November 9, 1881, and also held in the pokey for rustling cattle. Before the night was over, both outlaws were dragged from the jail by vigilantes and taken to the Grant House, where they were found guilty of being a general nuisance, along with the other crimes they had committed, and were promptly lynched. They were still hanging days later as a warning to others not to mess with Shakespeare.

The biggest threat to Shakespeare was the Apache Indians who were doing everything they could to get rid of the white settlers who had encroached upon their land. It is reported that up to seventy area citizens formed the Shakespeare Guard in the 1880s to protect the settlement from attacks, though not always with success.

In the early 1880s, the railroad pushed through the area, but to Shakespeare’s undoing, it missed the town by three miles, heading through Lordsburg instead. By this time, Shakespeare, according to onsite information, boasted three saloons, two hotels, two blacksmiths, a meat market, a mercantile store, and a lawyer. It also finally had a deputy sheriff. With the railroad, however, most of its businesses moved to Lordsburg. At the same time, the United States moved to the gold standard, putting the silver mines out of business. Most of Shakespeare’s residents moved on taking any salvageable material with them.

In 1907, when a new copper mine about a mile south of Shakespeare was built, the town saw a short resurgence, as miners rented many of the buildings in the old town. But, it was not enough to revive it permanently.

In 1935, Frank and Rita Hill purchased the town and buildings to utilize as a working ranch. They maintained and preserved one of the most intact ghost towns of the Old West. The entire town was declared a National Historic Site in 1970. That same year, Frank Hill passed away, but his wife, Rita, and daughter, Janaloo, continued to maintain the site. In 1984, Janaloo married Manny Hough and the following year, her mother, Rita, passed away.

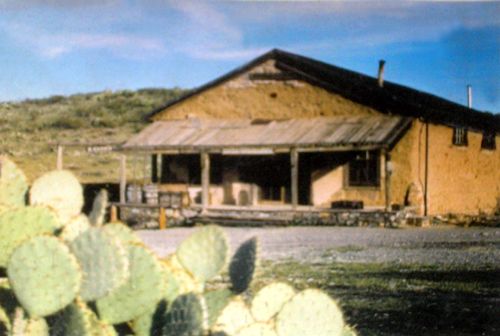

In 1997, Shakespeare lost its General Merchandise Store in a devastating fire. Unfortunately, for Manny and Janaloo, this was also their home, and much of her hard-earned research material, including photos and unpublished manuscripts, went up in smoke.

Janaloo, along with her new husband, continued to maintain the ranch and the town. A prolific writer, Janaloo was determined to keep Shakespeare’s history alive. Researching the “ranch,” its history, and collecting numerous photographs, she published a number of books until her untimely death in 2005.

Manny honored his wife and her family by continuing to preserve the ghost town and their legacy until his death in 2018.

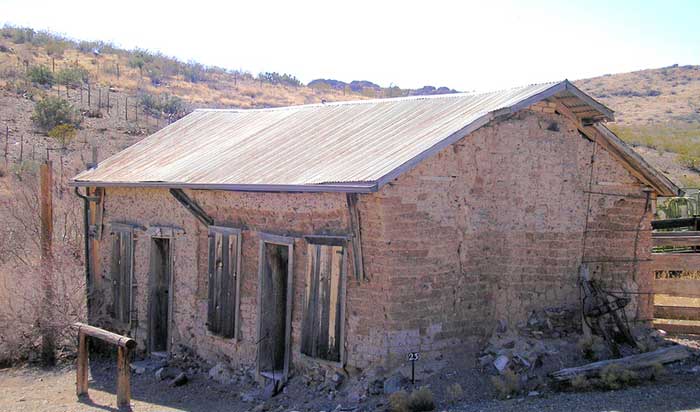

Shakespeare continues to be preserved, though it appears some of its history is embellished through tales passed down by old-timers. A number of buildings remain, including the Grant House, a saloon, the Stratford Hotel, a blacksmith shop, powder magazine, the assay office, and more. The Shakespeare Cemetery also continues to beckon visitors to visit some of the ghost town’s most colorful residents.

This historic General Merchandise Store, which served as Janaloo Hill and Manny Hough’s home was burned in a fire in 1997.

The ghost town was passed down to Manny’s daughter Gina and her husband, Dave. The town is now open daily from 10 to 5 and you can get a tour by calling from the gate or calling 505-542-9034 ahead of time. Several times a year, living history re-enactments are held at the historic site.

Shakespeare is located about three miles south of Lordsburg, New Mexico.

For more information:

Shakespeare Ghost Town

P.O. Box 253

Lordsburg, New Mexico 88045

505-542-9034

© Kathy Weiser-Dave Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2023.

Continue for clarification of Shakespeare’s relationship with Butterfields Overland Trail.

Clarification of Shakespeare as related to the Butterfield Trail, by Gerald T. Ahnert

Primary source references for Ralston/Shakespeare show that it was called Ralston, during its “Old West” period from approximately 1870 to 1879. Sometime around 1879, the name was changed to Shakespeare. “Dr. Myra Ellen Jenkins, New Mexico State Historian, says that there is no documentation to be found to prove there was a settlement here before the Civil War.” Ref: New Mexico Magazine, New Mexico Department of Development, 1974.

Human habitation of the site, other than Native Americans, starts from approximately 1870. An early reference was in the Democratic Enquirer, McArthur, Ohio, February 1, 1871:

“Glowing accounts are given of the richness of the new silver mines lately opened near Ralston, New Mexico. The average yield of the ore is said to be $2,282 per ton.”

By the statement “…new silver mines lately opened…” the discovery of the mines may have taken place about 1870.

In 1876 Lieutenant Philip Reade, the project leader for constructing telegraph lines along the Southern Overland Trail proposed that the line be constructed through Ralston. This gives an indication that, although the old Butterfield Trail was two miles north of Ralston, that the town was important enough to adjust the trail southward to pass through Ralston. (Ref: Arizona Citizen, Tucson, September 2, 1876). A later article in the same newspaper dated August 25, 1877, tells of the telegraph rates and that the line is now going through Ralston.

In the Arizona Sentinel, Yuma, Arizona Territory, May 23, 1874, appeared the following:

“New Mail Contractors. Kerens & Mitchell of Fort Smith, Arkansas, have newly established a stage line from between Mesilla, New Mexico, and San Diego, California.”

An article just below the above states:

“The Old Mail Contractors. The old mail contractors for carrying the mails between San Diego and Mesilla will soon retire and give place for the new [Kerens & Mitchell]…”

“The Old Mail Contractors” that the article eludes to is probably the stage line of Sanderson, Barlow & Co. In the Arizona Miner, Prescott, Arizona Territory, May 18, 1867, was the article “Mail at Last.” It tells of stage lines finally returning to the “…old Southern, or Butterfield, overland,…,” although some local stage services had been restored shortly after the Civil War ended. It is probable that Sanderson, Barlow & Co. made the slight adjustment the two miles south of the old Butterfield Trail to accommodate the new Ralston about 1870 or shortly after.

Although the many primary source references for Butterfield’s Overland Mail Company, 1858-1861, and those that predate that time, do not show the Southern Overland Trail going through the Ralston townsite, there are secondary references that allude to the Butterfield tail going through the townsite. Contemporary accounts state that there was a Butterfield stage station there even though none is listed in government reports by the Postmaster-General in Senate documents for that time.

A contemporary account was given by Janaloo Hill-Hough and her husband Manny Hough.

“Janaloo has passed on, but Manny and his group give tours of the townsite. The only contemporary account of a Butterfield station in Ralston comes from a story passed down to them by way of Emma Mable Muir who was told this by an old-timer by the name of John Evensen. The Hough’s have stated that what they were told was that Evensen was hired by the stage line of Kerens & Mitchell in 1865 to reopen the old Butterfield station for the line. According to the article in the Arizona Sentinel, Yuma, Arizona Territory, May 23, 1874, titled “The New Mail Contractors.” Kerens & Mitchell were stocking the trail between Mesilla and San Diego and would open the line for service in July 1874. This is nine years after the time that was related to the Houghs.”

The story passed down to them was published by Janaloo Hill-Hough in her brochure The Butterfield Overland Trail Through Hidalgo County. Unfortunately, the account is based only on local lore and not primary source references, as she states the Butterfield records were destroyed in the San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1905. This could not have happened since Butterfield’s Overland Mail Company office was not in San Francisco but in New York City. Some records from the company office have been preserved including minutes of the meetings. In almost every way this was a “New York State” line, as John Butterfield was from Utica, New York, and almost all the stagecoach drivers were from Upstate New York. Even the architect of the Butterfield Trail was Marquis L. Kenyon of Rome, New York.

Historian George Hackler in his book The Butterfield Trail in New Mexico gives a more complete accounting of Janaloo Hill-Hough and Manny Hough’s history of Shakespeare. Hackler’s correct conclusion concerning the handed-down story is “There is no direct evidence to support a station at Mexican Springs.” The handed-down account states that the name used for the area before Ralston existed was Mexican Springs.

For those who wish to have a more detailed accounting of the history of the Southern Overland Trail and the Butterfield Trail:

Goddard Bailey was assigned the task by Postmaster General Brown to take the first Butterfield Overland Mail Company stage leaving San Francisco and inspect the line to make sure it was meeting the government mail contract specifications. He lists all the stations. His report is titled “Report of the Postmaster-General” and was published in House of Representatives, Ex. Doc. No. 2, 35th Congress, 2d Session, 1858.

Ormsby, Waterman L. The Butterfield Overland Mail, The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA, 1991. From the Introduction, pvii, is the following: “The best narrative consists of a series of eight articles by Waterman L. Ormsby, published in six numbers of the New York Herald at intervals from September 26 to November 19, 1858. Ormsby, a special correspondent of the Herald, was the only through passenger on the first westbound stage.”

The Overland Mail Company contract – The Report of the Postmaster-General, Senate, 35th Congress, 2d Session, Ex. Doc. No. 48, pp. 7-10.

This government report, with maps, was based on Leach’s improvements through Arizona in September 1858 just as the first Butterfield stages were going through Arizona. His maps show the Butterfield Trail. James B. Leach, “REPORT UPON THE PACIFIC WAGON ROADS, CONSTRUCTED Under the direction of the Hon. Jacob Thompson, Secretary of the Interior, in 1857-’58-’59, El Paso to Yuma Wagon Road,” The Executive Documents, Second Session, Thirty-Fifty Congress, 1858-’59, pp. 9-11, 74-97. (Includes two maps).

Another major reference that contains California Column reconnaissance of the trail – War of the Rebellion, Vol. L, Part I, “Operations on the Pacific Coast, Washington, 1897

“San Antonio and San Diego Route,” The Senate of the United States, Second Session, Thirty-Fifth Congress, 1858-’59, Washington, 1859, p. 744.

©Gerald T. Ahnert, for Legends of America, October 2015.

Also See:

New Mexico – Land of Enchantment

New Mexico Ghost Towns and Mining Camps