By William H. Ryus in 1913

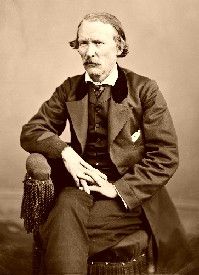

Christopher Carson, known among his friends as simply Kit Carson, was a Kentuckian by birth, having been born in December 1809. At the time of his birth, Kentucky was an almost pathless wilderness, rich with game, and along its river banks, the grasses grew so luxuriant that it invited settlers to settle there and build homes out of the trees that grew in such profusion. Small gardens were cultivated where corn, beans, onions, and a few other vegetables were raised, but families mainly subsisted on game, with which the forests abound, and the lakes and rivers were alive with fish. Wild geese, ducks, turkeys, quail, and pigeons swept through the air with perfect freedom. Deer, antelope, moose, beaver, wolves, catamount, and even grizzly bears often visited the scene of the settler’s home, among whom was our friend, Kit Carson.

Kit Carson had no education. There were no schools to attend other than the school of “trapping,” and he became a trapper, Indian guide, and interpreter.

When Kit was a small boy, his father moved, on foot, to Missouri, so history relates. At the time of the move, however, Missouri was not a state or even territory. France ceded to the United States the unexplored regions, which were, in 1800, called Upper Louisiana.

Kit’s father had a few white friends, trappers, and hunters, but the Indians were numerous. Mr. Carson and the other white families banded themselves together. They built a large log house, fashioned as both a house and a fort, if the occasion demanded, to fortify against a possible foe. The building was one story high, having portholes through which the muzzles of rifles could be thrust. As an additional precaution, they built palisades around the house. This house was built in what is now Howard County, Missouri, north of the Missouri River. At 15 years of age, Christopher Carson had never been to school a day, but he was “one of the Four Hundred,” equal to any man in his district. He was a fine marksman, an excellent horseman, of strong character and sound judgment. His disposition was quiet, amiable, and gentle. He was one of those boys who did things without boasting and did everything the best he could.

At about this stage of his life, his father put him out as an apprentice to learn a trade. The trade he was to learn was that of a “saddler.” However, the boy languished under the confinement and did not take to the business. He was a hunter and trapper by training, and nothing else would satisfy his nature.

One night, about two years later, when Kit was 18, a man who had chanced to pass his father’s humble home related his adventures. He told me how much would be earned by selling buffalo robes, buckskins, etc., in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He drew beautiful word pictures of wealth that could be attained in the great Spanish capital of New Mexico, more than a thousand miles from Missouri.

Soon, several able-bodied men decided to equip some pack mules and go to the great bonanza. They intended to live on game, which they would shoot on the way. Kit heard of the party and applied to them to let him accompany them. They were not only glad of his offer to go but considered they had a great need for him because he was so “handy” among the Indians. It turned out that Kit engineered the whole party. He had a military demeanor. When the mules were brought up and their packs fastened upon their backs, which required both skill and labor, Kit ordered the march, which was conducted with more than ordinary military precision.

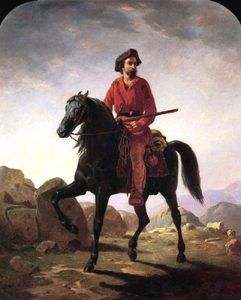

Kit Carson was a beloved friend of several tribes of Indians. He learned from them how to make his clothes, which he considered to be of much more artistic taste and style and more becoming than the tightly fitting store suits of a “Broadway dude” he had once “gazed upon.”

This suit he was so proud of consisted of a hunting shirt of soft, pliable deerskin ornamented with long fringes of buckskin dyed a bright vermillion or copperas. The trousers were made of the same material and ornamented with the same kind of fringes and porcupine quills of various colors. His cap was made of fur that could cover his head entirely, with “portholes” for his eyes, nose, and mouth. The mouth must be free to hold his clay pipe filled with tobacco. It is needless to say, he wore moccasins on his feet, beautified with many colored beads.

Before 1860, I was not personally acquainted with Kit Carson, but after that year, I knew him well. At Fort Union, New Mexico, he was the center of attraction from April 1, 1865, until April 1866. Everyone wanted to hear Kit tell of exploits he had been in, and he could tell a story well. Kit loved to play cards, and while he was as honest as the day was long, he was usually a winner. He didn’t like to put up much money. If he didn’t have a good hand, he would lie down.

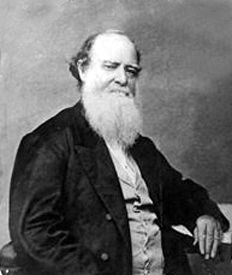

Kit Carson, like Colonel A.G. Boone, dealt honestly with the Indians. On several occasions, Kit Carson told me that had Colonel A. G. Boone remained the Indian agent, if the government had not withdrawn him, the great war with the Indians would never have occurred. Kit Carson was a born leader of men and was known from Missouri to Santa Fe—he was one of the most widely known men on the frontier.

Carson was the father of seven children. At the time of his death, his wife had already passed away in April 1868. His disease was an aneurysm of the aorta. A tumor pressing on the pneumo-gastric nerves and trachea caused frequent spasms of the bronchial tubes, which were exceedingly distressing. He died just a short time later, on May 23, 1868. His last words were addressed to his faithful doctor, H. R. Tilton, assistant surgeon of the United States Army, and were “Compadre adois” (dear friend, goodbye). In his will, he left property valued at $7,000 to his children.

Kit Carson’s first wife was an Indian Cheyenne girl of unusual intelligence and beauty. They had one girl child. After her birth, the mother only lived a short time. Kit tenderly reared this child until she reached eight years old, when he took her to St. Louis and liberally provided for all her wants. She received as good an education as St. Louis could afford and was introduced to the refining influences of polished society. She married a Californian and moved with him to his native state.

The Indians of today [1913] are possessed with the same ambitions as the whites. There are Indian lawyers, Indian doctors, Indian school teachers, and other educators, still in the frontier days when, from Leavenworth, Kansas, to Santa Fe, the plains were thronged with Indians. They were looked upon as uncivilized and were uncivilized, but were so severely abused that they ran out of their homes and were given no chances to become civilized or to learn any arts.

The Indians around Maxwell’s ranch were mainly lazy because they had nothing to do. Maxwell fed them, gave them some work, and gave the women considerable work — they wove blankets with a skill that cannot be surpassed by artists of today. Not only were these Indian women fine weavers, but they worked unceasingly on fine buckskin (they tanned their own hides), garments, beading them, embroidering them, working all kinds of profiles such as the profile of an Indian chief or brave animals of all kinds were beaded or embroidered into the clothes they made for the chiefs of their tribes. These suits were often sold to foreigners to take east as a souvenir, and they would sell them for the small sum of $200 to $300. Those Indian women would braid fine bridle reins of white, black, and sorrel horsehair for their chiefs and for sale to the white men. The Indian women were always busy but liked to see a horse race and their superior—their chief. An Indian woman is an excellent mother. While she cannot be classed as indulgent, she wants to train her children to endure hardships if they are called upon to endure them. She trains the little papoose to take to the cold water, not for the cleansing qualities, but for the “hardiness” she thinks it gives him.

By William H. Ryus, 1913. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2024.

About the Author: Excerpted from the book The Second William Penn – A True Account of Incidents that Happened Along the Old Santa Fe Trail, by William H. Ryus, 1913. The text, as it appears here, is not verbatim. William “Billy”. H. Ryus was better known as “the Second William Penn” by passengers and old settlers of the Santa Fe Trail because of his rare and exceptional knowledge of Indian traits and characteristics and his tactful ability to trade and treat with them. Ryus was one of the boy drivers of the stage company with U.S. Mail contracts, regularly running along the Santa Fe Trail. During this time, he routinely crossed the plains at a time when the West was still looked upon as “wild and wooly,” and in reality, was fraught with numerous, and often, murderous dangers.

Kit Carson’s home in Taos, New Mexico, is now a museum.

Also See:

Cimarron -Wild & Baudy Boomtown

Kit Carson – Legend of the Southwest

Kit Carson – The Nestor of the Rocky Mountains

Lucien Maxwell by a Santa Fe Trail Driver