America’s most visited National Park, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, straddles the border between North Carolina and Tennessee, preserving Southern Appalachian history’s rich cultural tapestry. World-renowned for its diversity of plant and animal life, the beauty of its ancient mountains, and the quality of its remnants of Southern Appalachian mountain culture, and the myriad of opportunities for exploring, hiking, touring, fishing, camping, and more.

The mountains have had a long human history spanning thousands of years — from the prehistoric Paleo Indians to early European settlement in the 1800s to loggers and Civilian Conservation Corps enrollees in the 20th century.

The park strives to protect the historic structures, landscapes, and artifacts that tell the varied stories of people who once called these mountains home.

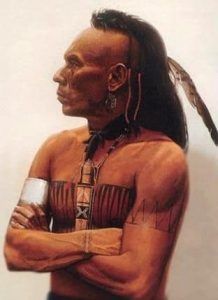

People have occupied these mountains since prehistoric times; but, it was not until the 20th century that human activities began to affect the natural course of events here profoundly. When the first white settlers reached the Great Smoky Mountains in the late 1700s, they found themselves in the land of the Cherokee Indians.

The tribe, one of the most culturally advanced on the continent, had permanent towns, cultivated croplands, sophisticated political systems, and extensive networks of trails. Most of the Cherokee were forcibly removed in the 1830s to Oklahoma in a tragic episode known as the Trail of Tears. The few who remained are the ancestors of the Cherokee living near the park today.

Life for the early European settlers was primitive, but by the 1900s, there was little difference between the mountain people and their contemporaries living in rural areas beyond the mountains. Earlier settlers had lived off the land by hunting the wildlife, utilizing the timber for buildings and fences, growing food, and pasturing livestock in the clearings. As the decades passed, many areas that had once been forest became fields and pastures. People farmed, attended church, hauled their grain to the mill, and maintained community ties in a typically rural fashion.

The agricultural pattern of life in the Great Smoky Mountains changed with lumbering in the early 1900s. Within 20 years, the largely self-sufficient economy of the people here was almost entirely replaced by dependence on manufactured items, store-bought food, and cash. Logging boom towns sprang up overnight at sites that still bear their names: Elkmont, Smokemont, Proctor, Tremont.

Loggers were rapidly cutting the great primeval forests that remained in these mountains. Unless the course of events could be quickly changed, little would be left of the region’s special character and wilderness resources. Intervention came when Great Smoky Mountains National Park was established in 1934, and the forest — at least the 20% that remained uncut within park boundaries — was saved.

Becoming a National Park was not easy for the Great Smokies. Joining the National Park System took a lot of money and the hard work of thousands of people. Establishing most of the older parks in the western United States, such as Yellowstone, was far easier as Congress merely carved them out of lands already owned by the government — often places where no one wanted to live anyway. But, getting parkland in this area was a different story. The land that became Great Smokies National Park was owned by hundreds of small farmers and a handful of large timber and paper companies. The farmers did not want to leave their family homesteads, nor did the large corporations want to abandon vast timber forests, many miles of railroad track, extensive systems of logging equipment, and whole villages of employee housing.

The idea to create a National Park in these mountains started in the late 1890s. A few farsighted people began to talk about a public land preserve in the cool, healthful air of the southern Appalachians. A bill even entered the North Carolina Legislature to this effect but failed. By the early 20th century, many more people in the North and South were pressuring Washington for a public preserve, but they were in disagreement on whether it should be a National Park or a national forest.

The drive to create a National Park became successful in the mid-1920s, with most hard-working supporters based in Knoxville, Tennessee, and Asheville, North Carolina.

In May 1926, a bill was signed by President Calvin Coolidge that provided for the establishment of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and Shenandoah National Park. This allowed the Department of the Interior to assume responsibility for the administration and protection of a park in the Smokies as soon as 150,000 acres of land had been purchased.

Since the government was not allowed to buy land for National Park use, the former political boosters became fundraisers. In the late 1920s, Tennessee and North Carolina Legislatures appropriated $2 million each for land purchases. Additional money was raised by individuals, private groups, and even schoolchildren.

By 1928, a total of $5 million had been raised. The trouble was that the land’s cost had now doubled, so the campaign ground to a halt. The day was saved when the Laura Spellman Rockefeller Memorial Fund donated $5 million, assuring the purchase of the remaining land.

But buying the land was difficult, even with the money in hand. Thousands of small farms, large tracts, and other miscellaneous parcels had to be surveyed, appraised, negotiated, and sometimes condemned in court.

More than 1,200 landowners had to leave their land once the park was established. They left behind many farm buildings, mills, schools, and churches. Over 70 of these structures have since been preserved so that Great Smoky Mountains National Park now contains the most extensive collection of historic log buildings in the East.

By 1934, the states of Tennessee and North Carolina had transferred deeds for 300,000 acres to the federal government. Congress thus authorized the full development of public facilities. Much of the early development of facilities and restoration of early settlers’ buildings was done by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). President Franklin Roosevelt formally dedicated the park in September 1940.

Today, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park is an outdoor paradise that includes over 800 miles of maintained trails for hikers and several campgrounds, fishing opportunities, and horseback riding. Wildlife viewing and auto touring are also popular activities. For the history buff, the park holds one of the best collections of log buildings in the eastern United States, including nearly 80 historic structures — houses, barns, outbuildings, churches, schools, and grist mills — which have been preserved or rehabilitated. Self-guiding auto tour booklets are available at each place to enhance your visit.

The Great Smoky Mountains National Park is open 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. However, some secondary roads, campgrounds, and other visitor facilities close in winter.

More Information:

Great Smoky Mountains National Park

107 Park Headquarters Road

Gatlinburg, Tennessee 37738

865-436-1200

Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser-Alexande/Legends of America, updated October 2021.

See our Smoky Mountains National Park Photo Gallery HERE

Also See:

The Legend of Daisy Town: A Journey Through Time in the Smoky Mountains