Nez Perce Warriors

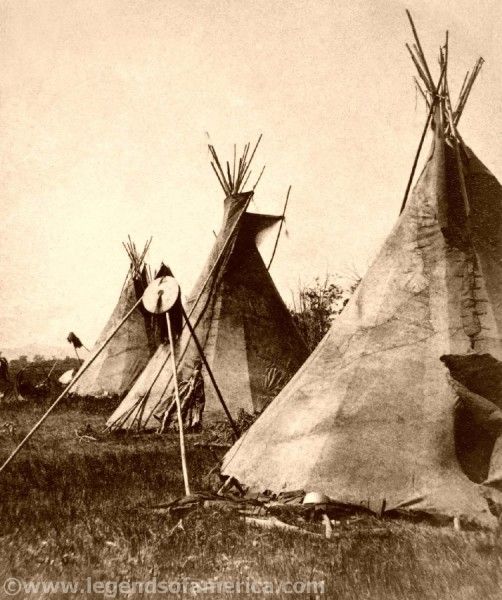

Once the largest congregation of tribes in the western United States, the Nez Perce were closely related to the Cayuse, Tenino and Umatilla tribes to their west. The tribe spanned across the open lands of the northwest, primarily in Idaho and Northern Washington, but traveled as far as the Great Plains during the hunting season.

The words Nez Perce means “those with pierced noses.” It was a name erroneously given to the tribe by Lewis and Clark on their travels in 1804 and 1805. The actual tribal name is Nee-Me-Poo, who never practiced nose piercing. Lewis and Clark mistook this band of Indians for another tribe living farther south.

The Nez Perce tribe actually represents many distinct bands with cultural differences that all existed together peacefully, and for that reason, they are usually thought of as being one tribe. In addition, their languages are closely related, all part of the Sahaptian branch of the Penutian language.

The tribe acquired horses in the mid-1700s and quickly becoming known for their outstanding horsemanship. They allied themselves closely with the other Penutian speakers, trading and hunting with them, generally on good terms. However, they were much less friendly with the tribes to the south and east, especially the Shoshoni, Bannock, and Blackfeet.

When the white man invaded their lands the tribe maintained peaceful relations with them for many years. In 1855 Chief Joseph’s father, Old Joseph, signed a treaty with the U.S. that allowed his people to retain much of their traditional lands. However, less than ten years later, in 1863, a second treaty severely reduced the Nez Perce lands, taking seven million acres from them as white settlers moved westward. Left with only 138,000 acres, Old Joseph maintained throughout his lifetime that this second treaty was never agreed to by his people.

The relatively peaceful relations with the white people came to an end in the 1870s when the United States withdrew the reservation status of the Wallowa Valley in northeastern Oregon in 1875.

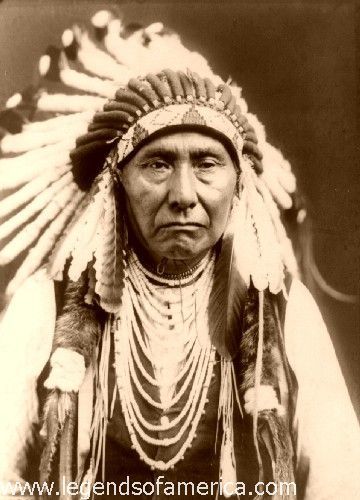

A showdown over the second “non-treaty” came after Chief Joseph (Hin-ma-toe-yah-laht-khit) assumed his role as Chief in 1877. When the tribe was ordered to go to the reservation, the Nez Perce refused to go. Chief Joseph, along with Chief Looking Glass, Chief White Bird, Chief Ollokot, Chief Lean Elk, and others soon led a band of 800 men, women and children west to Canada, a trip that lasted from June until October.

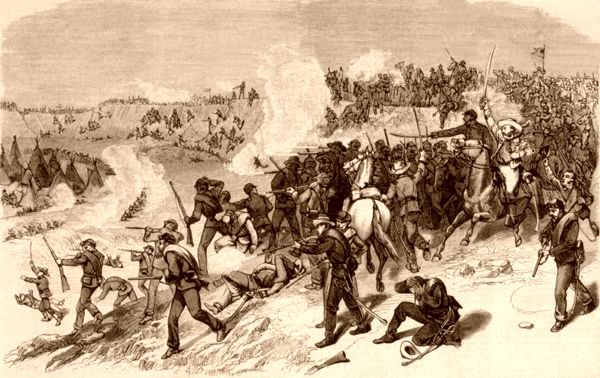

Hoping to seek safety with their Crow allies on the plains to the east, the band traveled more than 1,000 miles through Idaho and Montana with the U.S. Army was in hot pursuit. Fighting the army all along the trail, now referred to as the Nez Perce War, their size was severely reduced. Just forty miles from Canada they were trapped in Montana by the U.S. Army. After a five-day fight, the remaining 431 members of the tribe were beaten and Chief Joseph surrendered on October 5, 1877, with a speech that has become famous.

“I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Toohulhulsote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led the young men is dead.

It is cold and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are–perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead.

Hear me, my chiefs. I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

After the surrender, the tribe was to be kept at Fort Keogh, Montana, over the winter and then returned to their reservation. Instead, they were taken to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and placed between a lagoon and the Missouri River, where living conditions were terrible. Those who did not die were then taken to the Indian Territory, where the health situation was even worse. Many more died there from malaria and starvation.

Chief Joseph tried every possible appeal to the federal authorities to return the Nez Perce to the land of their ancestors. In 1885, he was sent along with many of his tribe members to a reservation in Washington where he died broken-spirited and broken-hearted in September of 1904.

Today, the Nez Perce have adapted to new ways of life and new religions, but the old Nez Perce faith is still quite alive and is passed down from generation to generation through stories and fables.

For the Nez Perce, the physical and spiritual aspects of life and nature are never separated. This is evident in their colorful celebrations and ceremonies. This way of life and these philosophies are still taught today on the reservations and in the surrounding schools.

Today, this sorrowful flight of events is recognized along the Nez Perce Trail, which stretches between Wallowa Lake, Oregon, to the Bear Paw Battlefield near Chinook, Montana.

© Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated February 2020.

Also See:

Chief Joseph – Leader of the Nez Perce