By Frederick Webb Hodge in 1906

The Elders say the men should look at women in a sacred way. The men should never put women down or shame them in any way. When we have problems, we should seek their counsel. We should share with them openly. A woman has intuitive thought. She has access to another system of knowledge that few men develop. She can help us understand. We must treat her in a good way.

-Native Wisdom

One of the most erroneous beliefs relating to the status and condition of the Native American woman is that she was, both before and after marriage, the abject slave and drudge of the men of her tribe. This view, due largely to inaccurate observation and misconception, was correct, perhaps, at times, as to a small percentage of the tribes and peoples whose social organization was of the most elementary kind, politically and ceremonially, and especially of those tribes that were nonagricultural.

Among the other Indian tribes north of Mexico, the status of women depended on complex conditions having their origin in climate, habitat, mythology, and concepts arising from the economic environment and in the character of the social and political organization.

One of the fundamental deductions of modern mythological research is that the prevailing social, ceremonial, and governmental principles and institutions of a people are closely reflected in the forms, structure, and kind of dominion exercised by the gods of that people.

Where numerous goddesses sat on the tribal Olympus, it is safe to say that woman was highly esteemed and exercised some measure of authority. In tribes whose government was based on clan organization, the gods were thought of as related to one another in degrees required by such an institution in which a woman is supreme, exercising rights at the foundation of tribal society and government.

Ethical teaching and observances find their explanation not in the religious views and rites of a people but rather in the rules and principles underlying those institutions which have proved most conducive to the peace, harmony, and prosperity of the community.

In defining the status of women, a broad distinction must be made between women who are. Women who are not members of the tribe or community, for among most tribes, life, liberty, and the pursuit of well-being are rights belonging only to women who, by birth or by the rite of adoption, are members or citizens. Other women receive no consideration or respect on account of their sex. However, after adoption, they were spared, as possible mothers, indiscriminate slaughter in the heat of battle, except while resisting the enemy as valiantly as their brothers and husbands when they suffered wounds or death for their patriotism.

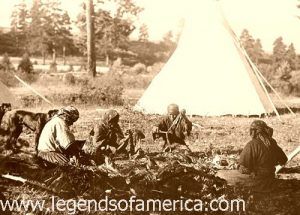

Among the North American aborigines dealt with here, each sex had its own peculiar sphere of duty and responsibility. It is essential to understand that these spheres of activity should be considered. To protect his family, his wife or wives, their offspring, and near kindred, to support them with the products of the chase, to manufacture weapons and wooden utensils, and commonly to provide suitable timbers and bark for the building of the lodge, constituted the duty and obligation which rested on the man. These activities required health, strength, and skill. The warrior was usually absent from his fireside on the chase, on the warpath, or on the fishing trip, weeks, months, and even years, during which he traveled hundreds of miles and was subjected to the hardships and perils of hunting and fighting, and to the inclemency of the weather, often without adequate shelter or food.

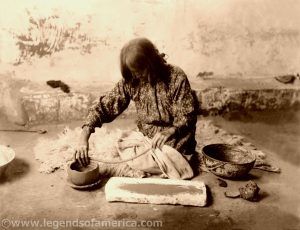

The labor required in the home and in all that directly affected it fell naturally to the lot of the woman. In addition to the activities which they shared in common with men, and the care of children, women attended to the tanning of skins, the weaving of suitable fibers into fabrics and other articles of necessity, the making of mats and mattresses, baskets, pots of clay, and utensils of bark; sewing, dyeing; gathering and storing of edible roots, seeds, berries, and plants, and the drying and smoking of meats brought home by the hunters.

The care of the camp equipment and the various family belongings on the march constituted part of the woman’s duties. She was assisted by the children and by any men who could not participate in active fighting or hunting.

The essential principle governing this division of labor and responsibility between the sexes lies much deeper than the heartless tyranny of man. It is the best possible adjustment of the available family means to secure the largest welfare measure and protect and perpetuate the little community. No other division was so well adapted to the conditions of life among the North American Indians.

Fortified by the doctrine of signatures and other superstitious reasons and beliefs, customs are emphasized by various rites and observances of the division of labor between the sexes.

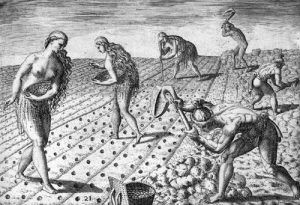

Thus, the sowing of seeds by women was supposed to render such seeds more fertile and the earth more productive than if planted by men, for it was held that women have and control the faculty of reproduction and increase. Hence, sowing and cultivating the crops became one of the exclusive departments of woman’s work.

According to Lewis and Clark, the Shoshone husband was the absolute proprietor of his wives and daughters and might dispose of them by barter or otherwise at his pleasure. Daniel Williams Harmon, a fur trader, and explorer, in his journal of 1820, described the women of the tribes he visited as having been treated no better than the dogs. W. L. Hardesty of the Hudson’s Bay Company said of the Kutchin and Loucheux Indians, “the women are literally beasts of burden to their lords and masters. All the heavy work is performed by them.” A similar statement was made by Stephen Powers, an American journalist, and ethnographer, in 1877 regarding the Karok of California.

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft described in his 1855 book, Indian Tribes, that the Cree women were subjected to lives of heavy and exacting toil and that some mothers would not hesitate to kill their female infants to save them from the miseries which they had suffered.

Samuel de Champlain, an explorer, geographer, and colonizer, wrote in 1615 that the Huron and Algonquian women were expected to attend their husbands from place to place in the fields, acting as a pack-mule in carrying the baggage and in doing several other things. Yet, it would seem that this hard life did not thwart their development, for he adds that among these tribes, several powerful women of extraordinary height had almost sole care of the lodge and the work at home, tilling the land, planting the corn, gathering a supply of fuel for winter use, beating and spinning the hemp and the bark fibers, the product of which was utilized in the manufacture fishing nets and other purposes; the women also harvested and stored the corn and prepared it for eating.

The duties of a woman of the Ottawa and Chippewa tribes were to bring into the lodge, of which she was the mistress, the meat which the husband left at the door; to dry, care and cook it; to get the fish at the landing or harbor and to prepare it for immediate use or storage; to fetch water; to spin various fibers to secure thread for various uses; to cut firewood in the surrounding forest; to clear land for planting and to raise and harvest the several kinds of grain and vegetables; to manufacture moccasins for the entire family; to make the sacks to hold grain, and the long or round mats used for covering the lodge or for mattresses; to tan the skins of the animals the men had killed, and to make robes of those which were used as furs.

She also made bark dishes while her husband or other male members of the household made those of wood; she designed many curious pieces of artwork; when her infant swathed on a cradleboard, she cried; she lulled it to sleep with song. On the move, the woman carried the lodge coverings if not conveyed by a canoe. In all her duties, she was aided by her children and dependents or guests, not rarely by the old men and the crippled who could still be of service.

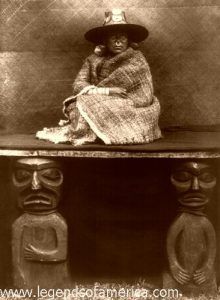

While the tribes of the northwest coast are distinct in language and physical features, and mental characteristics, they are nevertheless one in culture; their arts, industries, customs, and beliefs differ in so great a degree from those of all other Indian tribes that they constitute a well defined cultural group. The staple food of these Indians was supplied by the sea, from which the women gathered sea grass, which was cut and pressed into square cakes and dried for winter use. Clams and mussels were eaten fresh or strung on sticks or strands of bark and dried for winter consumption. Considerable quantities of berries and roots were also consumed. The dense forests along the coast furnished wood for building cabins, canoes, implements, and utensils. The Red Cedar was the most useful as it yielded the materials for a large part of their goods, its wood being utilized for building and carving, and its bark for manufacturing clothing and ropes, in which the women performed the greater part of the work. The women had their share also in the preparation and curing of the flesh and furs of the various game and fur-bearing animals that their husbands and brothers killed. They preserved berries and crab apples for winter use; the food was stored in spacious boxes made from cedar wood suitably bent, having bottoms sewn to their sides. Women assisted in curing and tanning the skins designed for clothing. Dog’s hair, mountain goat’s wool, and feathers were woven into fabrics suitable for wear or barter; soft cedar bark was also prepared for use as garments. The women made, in great quantity, a variety of baskets of rushes and cedar bark for storage and carrying purposes; mats of cedar bark, and in the South, of rushes, are made for bedding, packing, seats, dishes, and covers for boxes.

Frederick Webb Hodge, an authority on the Pueblo Indians, stated that monogamy was the rule among the Pueblos and that women’s status was much higher than in some other tribes. Among most of the Pueblos, the descent of blood, and hence of membership in the clan and citizenship in the tribe, was traced through the mother, the children belonging to her, or rather to her clan; that the home belonged to her, and that her husband, whom she could dismiss upon the slightest provocation, came to live with her. If she had daughters who married, the sons-in-law resided with her; it was not unusual to find men and women married dwelling together for life in perfect accord and contentment.

Labor was as equitably apportioned between the sexes as was possible under the conditions in which they lived; the small gardens, which were cultivated exclusively by the women, belonged to the women. In addition to performing all domestic duties, the carrying of water and the manufacturing of pottery were tasks done only by women. Some of the less irksome agricultural labor, especially at harvest time, was performed by the women. However, the men assisted her in heavier domestic work, such as house-building and fuel-gathering. The men also wove blankets, made moccasins for their wives, and assisted in other tasks usually regarded as pertaining exclusively to women.

According to Matilda Coxe Stevenson, an American ethnologist, she stated in 1904, in the Zuni tribe, an agricultural and pastoral people, the gardens were cultivated exclusively by the women and were inherited by the daughters. A married man carried the products of the fields to the house of his wife’s parents, which would then be his home. The wife, likewise, would place the produce of the plots of land derived from her father or mother with those of her husband, and while these stored products were designed to be utilized by the entire household, only the wife or the husband could remove them. Stevenson also said that a woman was a member of the Ashiwanni or Rain Priesthood, consisting of nine persons, and constituting one of the four fundamental religious groups in the hierarchical government of the Zuni; and that while the Zuni trace descent through the mother and have clans, these clans do not own the fields, as they do among the Iroquois.

However, by cultivation, a male could use any unoccupied plot of ground and dispose of it to anyone within the tribe. The daughters, and not the sons, inherited the landed property of the married Zuni man or woman. These few facts show plainly that the Zuni woman occupied a high status in the social and political organizations of her tribe.

Among the Iroquois and similar tribes, women controlled many of the fundamental institutions of society, including:

-

Descent of blood or citizenship in the clan, and hence in the tribe, was traced through her;

-

the titles, distinguished by unchanging specific names, of the various chieftainships of the tribe belonged exclusively to her;

-

the lodge and all its furnishings and equipment belonged to her;

-

her offspring, if she possessed any, belonged to her;

-

the clan’s lands (including the burial grounds in which her sons and brothers were interred) belonged to her.

Part of their duty was to keep a close watch on the policies and the course of affairs affecting the welfare of the tribe, to guard scrupulously the interests of the public treasury, with power to maintain its resources, consisting of strings and belts of wampum, quill and feather work, furs, corn, meal, fresh and dried or smoked meats, and of any other thing which could serve for defraying the various public expenses and obligations. They had a voice in the disposal of the contents of the treasury.

Every distinct and primordial family or clan had at least one of the female chiefs, who together constituted the clan council, and sometimes one of them, because of extraordinary merit and wisdom, was made regent in the event of a vacancy in the office of the regular male chief. Hence, some written accounts mention “queens” who ruled their tribes. Given the preceding facts, it is not surprising to find that among the Iroquoian tribes, the Susquehanna, the Huron, and the Iroquois; the penalties for killing a woman of the tribe were double those exacted for the killing of a man because, in the death of a woman, the Iroquoian lawgivers recognized the probable loss of a long line of prospective offspring.

Those Indian women of the northwest coast were not so fortunate, as the penalty for the killing of a woman of the tribe was only one-half that for the killing of a man. These instances show a great difference in the value placed on the life of a woman by tribes in widely separated areas.

Stephen Powers, journalist and ethnographer stated regarding the Yokut of California that although the husband took up his abode in the lodge of his wife or his father-in-law, he had the power of life and death over his wife. However, the statement cannot be accepted without qualification, meaning only that this power might be exerted to punish some specific crime and that it might not be exercised with impunity to satisfy the whim of the husband.

Captain John Smith, explorer, soldier, and author, described the Indian men of Virginia as devoting their time and energy to fishing, hunting, warfare, and other manly exercises outdoors. Still, within the lodge, they were often idle. Inside the lodge, the women and children performed the larger share of the work. The women made mats for their own use, trade, exchange, baskets, mortars, and pestles. They planted and gathered the corn and other vegetables, prepared and pounded the corn to obtain meals for their bread, and did all the cooking. They also cut and brought in all the wood used for fuel and, with the children’s help, fetched the water used in the lodge. Thus, the women were obliged in performing their duties to bear all kinds of burdens; but they willingly attended to their tasks at their own time and convenience and were not driven like slaves to do their duty. The descent of blood was traced through the mother.

In John Lawson’s, The History of Carolina, 1866, he said that a woman with a large number of children and with no husband to help support them was assisted by the young men in planting, reaping, and doing whatever she was incapable of performing herself.

He also said they eulogized a great man by citing that he had “many beautiful wives and children, esteemed the greatest blessings amongst these savages.” It would thus appear that the North Carolina native woman was not the drudge and slave of her husband or men of her tribe.

Concerning people of the same general region, explorer, William Bartram, said that among the Cherokee and the Creek Indians, scarcely a third as many women as men were seen at work in their fields. Spanish explorer and conquistador Hernando de Soto found in 1540 a woman whom he styled a queen ruling in the royal state a tribe on the Savannah River, indicating that woman in that early period was held in high esteem among these people.

Because of the possession of these vested rights, the woman exercised the sovereign right to select from her sons the candidates for the chieftainships of her clan and the tribe. Being the source of the life of the clan, the woman possessed the sole right to adopt aliens into it, and a man could adopt an alien as a kinsman only with the tacit consent of the matron of his clan. A mother possessed the important authority to forbid her sons from going on the warpath, and frequently the chiefs took advantage of this woman’s power to avoid a rupture with another tribe. The woman had the power of life or death over such alien prisoners as might become her share of the spoils of war to replace some of her kindred who may have been killed; she might demand from the clansmen of her husband or from those of her daughters, a captive or a scalp to replace a loss in her family. Thus it is evident that not only the clan and the tribal councils but also the League council were composed of her representatives, not those of the men.

Female chiefs were the executive officers of the women they represented, who provided public levies or contributions of food required at festivals, ceremonials, and general assemblies or for public charity. Part of their duty was to keep a close watch on the policies and the course of affairs affecting the welfare of the tribe, to guard scrupulously the interests of the public treasury, with power to maintain its resources, consisting of strings and belts of wampum, quill and feather work, furs, corn, meal, fresh and dried or smoked meats, and of any other thing which could serve for defraying the various public expenses and obligations. They had a voice in the disposal of the contents of the treasury.

In describing the character of the Muskhogean people, William Bartram, a Quaker Explorer, said in 1773: “I have been weeks and months amongst them, and in their towns, and never observed the least sign of contention or wrangling; never saw an instance of an Indian beating his wife, or even reproving her in anger… for indeed their wives merit their esteem and the most gentle treatment, they being industrious, frugal, careful, loving, and affectionate.”

He also said that they eulogized a great man by citing the fact that he had “a great many beautiful wives and children, esteemed the greatest blessings amongst these savages.” It would thus appear that the North Carolina native woman was not the drudge and slave of her husband or men of her tribe.

From what has been said, it is evident that the authority possessed by the Indian husband over his wife or wives was far from being as absolute as represented by careless observers, and there is certainly no ground for saying that the Indians generally kept their women in a condition of absolute subjection. The available information, instead, shows that while the married woman, because of her status as such, became a member of her husband’s household and owed him certain important duties and obligations, she enjoyed a large measure of independence and was treated with great consideration and deference, and had a marked influence over her husband. Of course, various tribes had different conditions to face. They possessed different institutions, so in some tribes, the wife was the equal of her husband, and in others, she was his superior in many things, as among the Iroquois.

In most, if not all, the highly organized tribes, the woman was the sole master of her body. Her husband or lover acquired marital control over her person by her own consent or by that of her family or clan elders. Captive alien women equally shared this respect for the person of the native woman. Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, the wife of a clergyman and a captive in 1676 for 12 weeks among the fierce Narraganset tribe, bears excellent witness. She wrote: “I have been in the midst of those roaring lions, and savage bears, that feared neither God, nor man, nor the devil, by day and by night, alone, and in company; sleeping, all sorts together, and not one of them ever offered the least abuse or unchastity to me in word or action.”

Roger Williams, an English Theologian and Native American supporter said with respect for the woman’s view: “So did never the Lord Jesus bring any unto his most pure worship, for he abhors, as all men, yea, the very Indians, an unwilling spouse to enter into forced relations” At a later day, and in the face of circumstances adverse to the Indians, General James Clinton, who commanded the New York division in the Sullivan Expedition in 1779 against the hostile Iroquois, paid his enemies the tribute of a soldier by writing in April 1779, to Colonel Van Schaick, then leading the troops against the Onondaga, the following terse compliment: “Bad as the savages are, they never violate the chastity of any woman, their prisoners.” However, there were cases in various tribes of violation of women, but the guilty men were regarded with horror and aversion. The culprits, if apprehended, were punished by the kindred of the woman if single and by her husband and his friends if married.

Among the Sioux and the Yuchi tribes, men who made a practice of seduction were in grave bodily danger from the aggrieved women and girls, and the resort by the latter to extreme measures was sanctioned by public opinion as properly avenging a gross violation of woman’s inalienable right, the control of her own body. When such was given, the dower or bride price did not confer, it seems, on the husband, absolute right over the life and liberty of the wife: it was rather a compensation to her kindred and household for the loss of her services. Among the Navajo, the husband possessed very little authority over his wife, although he often “obtained” her by paying a bride price or present.

Among all the tribes, women, during her menstrual period and, among many of the tribes, during the period of gestation and childbirth, were regarded as abnormal, extra-human, and sacred, in the belief that her condition revealed the magic power so potent, that if not segregated from the ordinary haunts of men, would disturb the usual course of nature. Therefore, she was tabooed during these periods; however, these recurrent and temporary taboos did not affect the status of the woman in the social and political organization in any way detrimental to her interests.

It also appears that in many instances, women aspired to excel in some of the vocations which might be regarded as peculiar to the male sex, such as hunting, fishing, fowling, and fighting beside the man. At times, she was famed, even notorious, as a sorceress. Some of the weirdest tales of sorcery and incantation are connected with the lives and deeds of noted woman sorcerers who delighted in torture and the destruction of human life.

Some maintain that the institution of maternal descent tends to elevate the social status of women. However, apart from the independence of the women, brought about by purely economic activities arising from the cultivation of the soil, it is doubtful whether the women ever attained any large degree of independence and authority aside from this potent cause.

Without a detailed and carefully compiled body of facts concerning the activities and the relations of the sexes, and the relation of each to the various community institutions, this question cannot be satisfactorily decided.

The information concerning the rights of women, as compared with those of men, found in historical accounts of various tribes are so meager and indefinite that it is difficult, if not impossible, to define accurately the effect of either female or male descent on the status of the woman. It is apparent, however, that among the sedentary and agricultural communities, the woman enjoyed a large, if not a preponderating, measure of independence and authority, greater or less in proportion to the extent of the community’s dependence for daily sustenance on the product of the woman’s activities.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

About the Article: The majority of this historic text was published in the Handbook of American Indians, written by Frederick Webb Hodge and published in 1906. Hodge (1864-1956) was an editor, anthropologist, archaeologist, and historian who published more than 350 items, including books, monographs, and articles in scientific and historical journals. In addition to his research, excavations, and writing activities, he was employed by the Smithsonian Institution, the Bureau of American Ethnology, the Museum of the American Indian in New York City and served as a member and officer of several organizations. Though the essence of his article is essentially intact, the text that appears on this page is far from verbatim, as additions, updates, and editing has occurred for clarity and ease for the modern reader.

Also See:

Native America Heroes and Leaders

Native Americans – First Owners of America

Native American Photo Galleries