The Ghost Dance (Natdia) is a spiritual movement that came about in the late 1880s when conditions were bad on Indian reservations and Native Americans needed something to give them hope. This movement found its origin in a Paiute Indian named Wovoka, who announced that he was the messiah come to earth to prepare the Indians for their salvation.

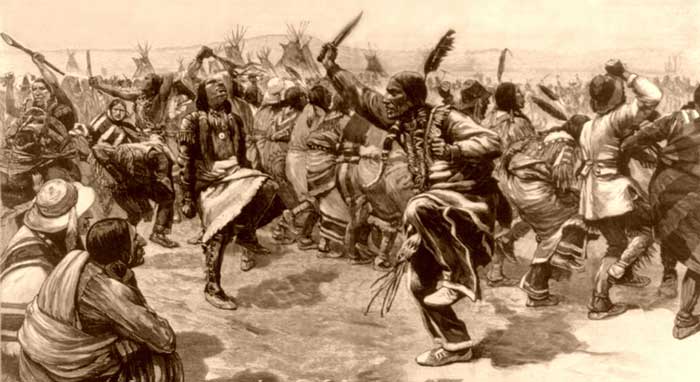

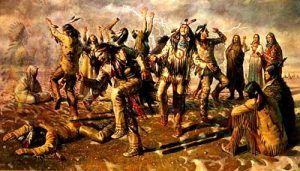

The Paiute tradition that led to the Ghost Dance began in the 1870s in the Western Great Basin from the visions of Wodziwob (Gray Hair) concerning earth renewal and the reintroduction of the spirits of ancient Numu (Northern Paiute) ancestors into the contemporary day to help them. Central to the Natdia religion was the dance itself – dancing in a circular pattern continuously – which induced a state of religious ecstasy.

Wovoka

The movement began with a dream by Wovoka (named Jack Wilson in English), a Northern Paiute, during the solar eclipse on January 1, 1889. He claimed that, in his dream, he was taken into the spirit world and saw all Native Americans being taken up into the sky and the Earth opening up to swallow all Whites and to revert back to its natural state. The Native Americans, along with their ancestors, were put back upon the earth to live in peace. He also claimed that he was shown that, by dancing the round-dance continuously, the dream would become a reality and the participants would enjoy the new Earth.

His teachings followed a previous Paiute tradition predicting a Paiute renaissance. Varying somewhat, it contained much Christian doctrine. He also told them to remain peaceful and keep the reason for the dance secret from the Whites. Wovoka’s message spread quickly to other Native American peoples and soon many of them were fully dedicated to the movement. Representatives from tribes all over the nation came to Nevada to meet with Wovoka and learn to dance the Ghost Dance and to sing Ghost Dance songs.

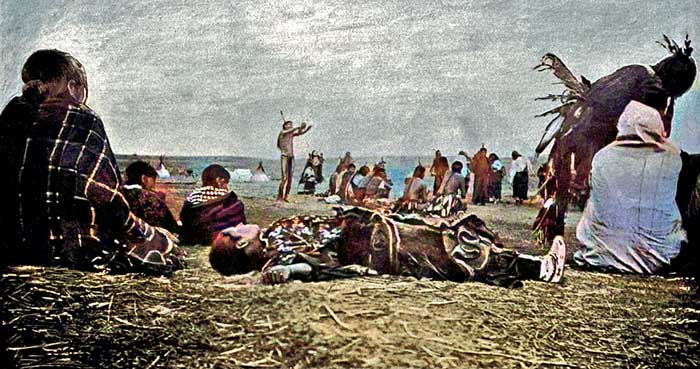

A Native American Woman Ghost Dancer Unconscious After Hours Of Emotional Ritual. Touch of color LOA.

The dance as told by Wovoka went something like this: “When you get home you must begin a dance and continue for five days. Dance for four successive nights, and on the last night continue dancing until the morning of the fifth day when all must bathe in the river and then return to their homes. You must all do this in the same way. …I want you to dance every six weeks. Make a feast at the dance and have food that everybody may eat.”

The Natdia, it was claimed, would bring about the renewal of the native society and decline in the influence of the Whites.

Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) agents grew disturbed when they became aware that so many Indians were coming together and participating in a new and unknown event.

In early October 1890, Kicking Bear, a Minneconjou Sioux Indian, visited Sitting Bull at Standing Rock telling him of his visit to Wovoka. They told him of the great number of other Indians who were there as well, referring to Wovoka as the Christ.

And they told him of the prophecy that the next spring when the grass was high, the earth would be covered with new soil and bury all the white men. The new soil would be covered with sweetgrass, running water and trees and the great herds of buffalo and wild horses would return. All Indians who danced the Ghost Dance would be taken up into the air and suspended there while the new earth was being laid down. Then they would be returned to the earth along with the ghosts of their ancestors.

When the dance spread to the Lakota, the BIA agents became alarmed. They claimed that the Lakota developed a militaristic approach to the dance and began making “ghost shirts” they thought would protect them from bullets. They also spoke openly about why they were dancing. The BIA agent in charge of the Lakota eventually sent the tribal police to arrest Sitting Bull, a leader respected among the Lakota, to force him to stop the dance. In the struggle that followed, Sitting Bull was killed along with a number of policemen. A small detachment of cavalry eventually rescued the remaining policemen.

Wounded Knee Burial Site. Photo by Kathy Alexander.

Following the killing of Sitting Bull, the United States sent the Seventh Cavalry to “disarm the Lakota and take control.” During the events that followed, now known as the Wounded Knee Massacre on December 29, 1890, 457 U.S. soldiers opened fire upon the Sioux killing more than 200 of them. The Ghost Dance reached its peak just before the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890.

When it became apparent that ghost shirts did not protect from bullets and the expected resurrection did not happen, most former believers quit the Ghost Dance. Wovoka, disturbed by the death threats and disappointed with the many reinterpretations of his vision, gave up his public speaking. However, he remained well-respected among his followers and continued his religious activities. He traveled and received visitors until the end of his life in 1932. There are still members of the religious movement today.

Believers in the Ghost Dance spirituality are convinced that performing the Ghost Dance will eventually reunite them with their ancestors coming by railway from the spirit world. The ancestor spirits, including the spirit of Jesus, are called upon to heal the sick and to help protect Mother Earth. Meanwhile, the world will return to a primordial state of natural beauty, opening up to swallow up all other people (those who do not have a strong spirituality based upon the earth). The performers of the Ghost Dance theoretically will float in safety above with their ancestors, family, and peoples of the world who follow the extensive spirituality.

Ghost Dance in 1913 with Cheyenne & Arapahoe tribal members. Photo by Adolph F. Muhr, 1913. Touch of color by LOA.

1890 Observation and Description of the Ghost Dance:

Mrs. Z.A. Parker observed the Ghost Dance among the Lakota at Pine Ridge Reservation, Dakota Territory on June 20, 1890, and described it:

We drove to this spot at about 10:30 o’clock on a delightful October day. We came upon tents scattered here and there in low, sheltered places long before reaching the dance ground. Presently we saw over three hundred tents placed in a circle, with a large pine tree in the center, which was covered with strips of cloth of various colors, eagle feathers, stuffed birds, claws, and horns-all offerings to the Great Spirit. The ceremonies had just begun. In the center, around the tree, were gathered their medicine-men; also those who had been so fortunate as to have had visions and in them had seen and talked with friends who had died. A company of 15 had started a chant and were marching abreast, others coming in behind as they marched. After marching around the circle of tents they turned to the center, where many had gathered and were seated on the ground.

I think they wore the ghost shirt or ghost dress for the first time that day. I noticed that these were all new and were worn by about seventy men and forty women. The wife of a man called Return-from-scout had seen in a vision that her friends all wore a similar robe, and on reviving from her trance she called the women together and they made a great number of the sacred garments. They were of white cotton cloth. The women’s dress was cut like their ordinary dress, a loose robe with wide, flowing sleeves, painted blue in the neck, in the shape of a three-cornered handkerchief, with moon, stars, birds, etc., interspersed with real feathers, painted on the waists, letting them fall to within three inches of the ground, the fringe at the bottom. In the hair, near the crown, a feather was tied. I noticed an absence of any manner of head ornaments, and, as I knew their vanity and fondness for them, wondered why it was. Upon making inquiries I found they discarded everything they could which was made by white men.

The ghost shirt for the men was made of the same material-shirts and leggings painted in red. Some of the leggings were painted in stripes running up and down, others running around. The shirt was painted blue around the neck, and the whole garment was fantastically sprinkled with figures of birds, bows and arrows, sun, moon, and stars, and everything they saw in nature.

Down the outside of the sleeve were rows of feathers tied by the quill ends and left to fly in the breeze, and also a row around the neck and up and down the outside of the leggings. I noticed that a number had stuffed birds, squirrel heads, etc., tied in their long hair. The faces of all were painted red with a black half-moon on the forehead or on one cheek.

As the crowd gathered about the tree the high priest, or master of ceremonies, began his address, giving them directions as to the chant and other matters. After he had spoken for about fifteen minutes they arose and formed in a circle. As nearly as I could count, there were between three and four hundred persons.

One stood directly behind another, each with his hands on his neighbor’s shoulders. After walking about a few times, chanting, “Father, I come,” they stopped marching, but remained in the circle, and set up the most fearful, heart-piercing wails I ever heard-crying, moaning, groaning, and shrieking out their grief, and naming over their departed friends and relatives, at the same time taking up handfuls of dust at their feet, washing their hands in it, and throwing it over their heads.

Finally, they raised their eyes to heaven, their hands clasped high above their heads, and stood straight and perfectly still, invoking the power of the Great Spirit to allow them to see and talk with their people who had died. This ceremony lasted about fifteen minutes, when they all sat down where they were and listened to another address, which I did not understand, but which I afterward learned were words of encouragement and assurance of the coming messiah.

When they arose again, they enlarged the circle by facing toward the center, taking hold of hands, and moving around in the manner of school children in their play of “needle’s eye.” And now the most intense excitement began. They would go as fast as they could, their hands moving from side to side, their bodies swaying, their arms, with hands gripped tightly in their neighbors’, swinging back and forth with all their might. If one, more weak and frail, came near falling, he would be jerked up and into position until tired nature gave way.

The ground had been worked and worn by many feet until the fine, flour-like dust lay light and loose to the depth of two or three inches. The wind, which had increased, would sometimes take it up, enveloping the dancers and hiding them from view. In the ring were men, women, and children; the strong and the robust, the weak consumptive, and those near to death’s door. They believed those who were sick would be cured by joining in the dance and losing consciousness. From the beginning they chanted, to a monotonous tune, the words:Father, I come;

Mother, I come;

Brother, I come;

Father, give us back our arrows.

All of which they would repeat over and over again until first one and then another would break from the ring and stagger away and fall down. One woman fell a few feet from me. She came toward us, her hair flying over her face, which was purple, looking as if the blood would burst through; her hands and arms moving wildly; every breath a pant and a groan; and she fell on her back, and went down like a log. I stepped up to her as she lay there motionless, but with every muscle twitching and quivering. She seemed to be perfectly unconscious. Some of the men and a few of the women would run, stepping high and pawing the air in a frightful manner. Some told me afterward that they had a sensation as if the ground were rising toward them and would strike them in the face. Others would drop where they stood. One woman fell directly into the ring, and her husband stepped out and stood over her to prevent them from trampling upon her. No one ever disturbed those who fell or took any notice of them except to keep the crowd away.

They kept up dancing until fully 100 persons were lying unconscious. Then they stopped and seated themselves in a circle, and as each recovered from his trance he was brought to the center of the ring to relate his experience. Each told his story to the medicine man, and he shouted it to the crowd. Not one in ten claimed that he saw anything. I asked one Indian, a tall, strong fellow, straight as an arrow-what his experience was. He said he saw an eagle coming toward him. It flew around and around, drawing nearer and nearer until he put out his hand to take it when it was gone. I asked him what he thought of it. “Big lie,” he replied. I found by talking to them that not one in 20 believed it. After resting for a time they would go through the same performance, perhaps three times a day. They practiced fasting, and every morning those who joined in the dance were obliged to immerse themselves in the creek. – Z.A. Parker, 1890.

© Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated February 2020.

Also See:

Native American Rituals and Ceremonies

Native American Photo Galleries

The Father Comes Singing

There is the father coming,

There is the father coming.

The father says this as he comes,

The father says this as he comes,

“You shall live,” he says as he comes,

“You shall live,” ‘he says as he comes.

– Sioux Ghost Dance Song