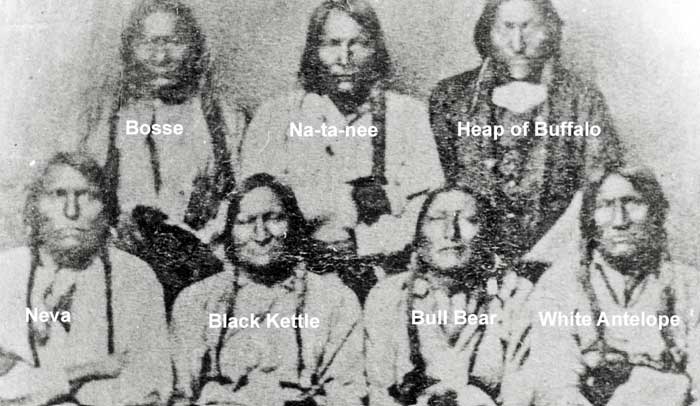

Peace Chiefs at Camp Weld Council in 1864.

All we ask is that we have peace with the whites. We want to hold you by the hand. You are our father. We have been traveling through a cloud. The sky has been dark ever since the war began. We want to take good tidings home to our people, that they may sleep in peace. I want you to give all these chiefs of the soldiers here to understand that we are for peace and that we have made peace, that we may not be mistaken by them for enemies. I have not come here with a little wolf bark, but have come to talk plain with you.

— Motavato (Black Kettle) speaking to Colorado Governor Evans, Colonel Chivington, Major Wynkoop & others in Denver, autumn, 1864

Called Motavato or Moke-ta-ve-to by his friends and family, Black Kettle was born near the Black Hills of South Dakota in 1803. However, by 1832, he had roamed south and joined the Southern Cheyenne tribe. Decades later, after having displayed strong leadership skills, he became chief of the Wuhtapiu group of the Cheyenne in 1861.

Living in the vast territory of western Kansas and eastern Colorado, Black Kettle and his band enjoyed the peace guaranteed to the Cheyenne under the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851. However, by the time he became chief, the 1859 Pikes Peak gold rush had sparked a flood of people encroaching upon their lands in Colorado. Even the U.S. Indian Commissioner admitted, “We have substantially taken possession of the country and deprived the Indians of their accustomed means of support.” Instead of upholding the Fort Laramie Treaty, the government sought to resolve the situation by demanding the Southern Cheyenne sign a new treaty ceding all their lands except the small Sand Creek reservation in southeastern Colorado.

Black Kettle, fearing that if he didn’t agree, a less favorable settlement might be presented, agreed to the treaty in 1861 and did what he could to see that the Cheyenne obeyed its provisions. However, the Sand Creek reservation could not sustain the Cheyenne Indians forced to live there. The barren tract of land was unfit for farming, and the nearest herd of buffalo was over two hundred miles away. In addition, the reservation soon became a breeding ground for several diseases that left numerous dead in their wake. Desperate, many of the young Cheyenne braves began to leave the reservation, preying on the livestock of nearby settlers and stealing the supplies of passing wagon trains and mining camps to the west.

As the Civil War progressed in the east, the number of soldiers in the area significantly decreased, and without protection, the Indians accelerated their attacks. However, the area settlers were enraged and soon formed a volunteer militia which led to the Colorado War of 1864-1865 and one of the most infamous incidents of the Indian Wars – the Sand Creek Massacre. In this brutal attack, some 150 Indians lay dead, most of which were old men, women, and children. Though Black Kettle miraculously escaped harm at Sand Creek, his wife was shot several times.

Always a peaceful man, Black Kettle continued to counsel peace, even as the Cheyenne struck back with continued raids on wagon trains and nearby ranches. By October 1865, he and other Indian leaders had arranged an uneasy truce on the plains, signing a new treaty that exchanged the Sand Creek Reservation for reservations in southwestern Kansas. However, these did not include their former Kansas hunting grounds.

Prisoners from Black Kettles camp, captured by General Custer, Theodore R.Davis,1868. Click for prints & products.

As Black Kettle led his band to Kansas, many refused to follow and instead headed north to join the Northern Cheyenne in Lakota territory. Yet others ignored the treaty altogether and continued to roam over their ancestral lands. These roaming braves referred to as Dog Soldiers, soon allied themselves with Cheyenne war chief Roman Nose.

The U.S. Government, angered by the Cheyenne’s refusal to obey the treaty, soon sent in General William Tecumseh Sherman to force them onto their assigned lands. However, Roman Nose and his followers struck back by continuing to attack so many westward-bound pioneers that it soon halted all traffic across western Kansas for a time. Seeking to resolve the conflict after years of attacks, the U.S. Government sought to move the Cheyenne again, this time onto two smaller reservations in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma.)

Chief Black Kettle

There, the Indians were promised that they would receive annual provisions of food and supplies. Black Kettle was once again among the leaders who signed the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867. However, once he moved his band to the new reservation, the promised provisions were never given, and by year’s end, even more of the Cheyenne braves had joined with Roman Nose.

As these renegade Cheyenne continued to raid farms in Kansas and Colorado, General Philip Sheridan once again launched a campaign against the Cheyenne encampments. Seventh Cavalry Commander George Armstrong Custer, taking the lead in one campaign, followed the tracks of a small raiding party to a Cheyenne village on the Washita River. Well within the boundaries of the Cheyenne reservation, it was Black Kettle’s village. Though a white flag flew above Black Kettle’s tipi, Custer ordered an attack on the village at dawn on November 27, 1868. Black Kettle and his wife would die, along with approximately 150 warriors and an estimated 20 or more civilians. The rest of the camp were taken as prisoners.

Cheyenne Warriors by Edward S. Curtis, 1905. Color by LOA.

Dying with Black Kettle was the Cheyenne’s hope of sustaining themselves as independent people. By the next year, all had been driven from the plains and confined to reservations.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2022.