By George Bird Grinnell in 1913

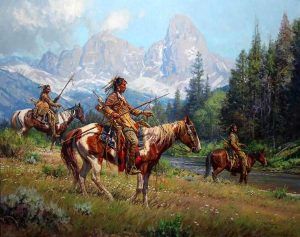

Long ago, before our fathers or grandfathers were born, white people did not know anything about the western half of North America; the Indians who told these stories lived on the Western plains. High mountains to the west of their home rose black with pine trees on their lower slopes and capped with snow, but their tents were pitched on the rolling prairie. For a little while in spring, this prairie was green and dotted with flowers, but for most of the year, it stretched away brown and bare, north, east, and south, farther than one could see.

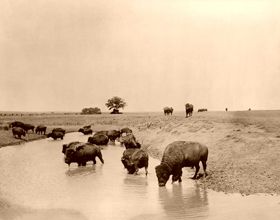

On these plains were many kinds of wild animals. Sometimes, the prairie was crowded with herds of black buffalo running in fear, or, again, the herds, unfrightened, fed, scattered out so that the hills far and near were dotted with their dark forms. Among the buffalo were yellow and white antelopes—many of them graceful and swift in their feet.

Feeding on the high prairie or going down into the wooded river valleys to drink were herds of elk, while the willow thickets, the brushy ravines, and the lower timbered foot-hills sheltered deer.

The naked Bad Lands, the rocky slopes of the mountains, and the tall buttes that often rise above the level prairie were the refuge of the mountain sheep, which in those days, like all the other grass eaters of the region, grazed on the prairie and sought the more broken, higher country only when alarmed or when they wished to rest.

These were the animals that the Blackfoot killed for food before the white men came, and of these, the buffalo was the chief. Buffalo could be captured in numbers more than any other animals, and the Blackfoot, like the other Plains Indians, had devised a method for taking them so that when the buffalo were near, the Blackfoot never suffered from hunger. Yet sometimes, the buffalo went away, and the lonely, far-traveling scouts sent out by the tribe could not find them. Then, the people had to turn to the smaller animals — the elk, deer, antelope, and wild sheep.

Before they had horses, they did not make long marches in those old days when they moved. Their only domestic animal was the dog, used chiefly as a beast of burden, either carrying loads on its back or hauling a travois formed by two long sticks crossing above the shoulders and dragging on the ground behind. Behind the dog, these two sticks were united by a little platform, which was lashed some small burden — sometimes a baby.

In those days, when people moved from one place to another, all who were large enough to walk and strong enough to carry a burden on their shoulders were laden. Usually, men, women, and children bore loads suited to their strength. Yet sometimes, the men carried no loads at all, for if journeying through a country where they feared that some enemy might attack them, the men must be ready to fight and to defend their wives and children. A man cannot fight well if he carries a burden; he cannot use his arms readily nor run about lightly — forward to attack, backward in retreat. If he is not free to fight well, his family will be in danger. White men who have seen Indians journeying in this way and who have not understood why some women carried heavy loads, and the men carried nothing have said that Indian men were idle and lazy and forced their women to do all the work. Those who wrote those things were mistaken in what they said. They did not understand what they saw. The truth is that these men were prepared for the danger of enemies’ attacks and were ready to do their best to save their families from harm.

Carrying on their backs all their property, except the little the dogs might pack, it is evident that the Indians in those days could not make long journeys.

In those days, they had no buckets of wood or tin to carry water. So, instead, they used a vessel like a bag or sack made from the soft membrane of one of the buffalo’s stomachs. After it had been cleansed and all the openings from it save one had been tied up, the women filled it at the stream with a spoon made of buffalo horn or with a larger ladle of the horn of the wild sheep.

Because this water skin was soft and flexible, it could not stand on the ground, so they hung it up, sometimes on the limb of a tree, more often on one of the lodge poles, or sometimes on a tripod—three sticks coming together at the top and standing spread out at the ground.

Most of the meat cooked for the family was roasted, yet much of it was boiled, sometimes in a bowl of stone, sometimes in a kettle made of a fresh hide or the paunch of the buffalo. Sometimes, these skin or paunch kettles were supported at the sides by stakes stuck in the ground, and sometimes, a hole dug in the ground was lined with the hide, which was so arranged as to be watertight.

As may be imagined, they were not put over a fire, but this water was heated in quite another way when filled with cold water. Nearby, a fire was built, in which large stones were thrown, and on top of the stones, more wood was piled; after a time, when the wood had burnt down, the stones were very hot — sometimes red hot.

With two rather short-handled forked sticks, the women took one of the hot stones from the fire and put it in the water in the hide kettle, and as it cooled, they took it out and put another hot stone. Thus, the water was soon heated, boiled, and cooked whatever was in the kettle. There were some ashes and a little dirt in the soup, but that was not regarded as important.

This was long before the Indians knew of matches or flint and steel. In those days, making a fire was not easy and took a long time. By his knees or feet, a man held in position on the ground a piece of soft, dry wood in which two or three little hollows had been dug out, and taking another slender stick of hardwood and pressing the point in one of the little hollows in the stick of softwood. He twirled the stick rapidly between the palms of his hands, so fast and so long that presently, the dust ground from the softer stick, falling to one side in a little pile, began to smoke. At last, a faint spark was seen at the top of the pile, which began to glow and, spreading, became constantly larger. He, or his companion, for often two men twirled the stick, one relieving the other, caught this spark in a bit of tinder — perhaps some dry punk or a little fine grass — and by blowing coaxed it into flame, and there was the fire.

This fire-making was hard work, and the people tried to escape this work by always keeping a spark of fire alive. To do this, men sometimes carried the hollow tip of a buffalo horn by a thong slung over the shoulder, the opening of which was closed by a wooden plug. When going on a journey, the man lighted a piece of punk and, placing it in this horn, plugged up the open end so that no air could get into it. There, the punk smoldered for a long time and neither went out nor was wholly consumed. Once in a while during the day, the man looked at this punk, and if he saw that it was almost consumed, he lit another piece, put it in the horn, and replaced the plug.

So, at night, when he reached camp, the fire was still in his horn, and he could readily kindle a blaze, and other fires were kindled from this blaze. Often, if the camp was large, the first young men who reached it gathered wood and perhaps kindled four fires, and after the women had reached the camp, unpacked their dogs, and put up their lodges, each woman would go to one of these fires to get a brand or some coals with which to start her own lodge fire.

In warm weather, men and boys wore little clothing. They went almost naked, yet each man or woman was usually wrapped in a warm robe of tanned buffalo skin in cold weather. Even the little children wore robes, the smallest ones taken from the little buffalo calves. All their clothing, like their beds and homes, was made of the skins of animals. Shirts, women’s dresses, leggings, and moccasins were made from the tanned skins of buffalo, deer, antelope, and mountain sheep. Often, the moccasins were made from the smoked skin cut from the top of an old lodge, for this skin had been smoked so much that it never dried hard and stiff after it had been wet. The moccasins had a stiff sole of buffalo rawhide, and in the bottom of this sole were cut one or two holes so that the water might run out if a man had to wade through a stream.

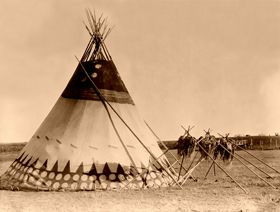

The homes of these Indians were lodges—tents made of tanned buffalo skin supported on a cone of long, straight, slender poles. At the top where the poles crossed, an opening for the smoke from the fire built in the center of the circular lodge floor was built. Around the fire and close under the lodge covering were the beds where the people slept or ate during the day.

These homes were warm and comfortable. The border of the lodge covering did not come down quite to the ground, but inside the lodge poles, and tied to them, was a long, wide strip of tanned buffalo skin four or five feet high and long enough to reach around the inside of the lodge, almost from one side of the door to the other.

This strip of tanned skin — made up of several pieces — was so broad that one edge rested on the floor and reached inward under the beds and seats.

Through the open space between the lodge covering and the lodge lining, fresh air kept passing into the lodge close to the ground, up over the lining, and down toward the center of the lodge, furnishing draught for the fire. The lodge lining kept this cold air from blowing directly on the lodge’s occupants, who sat around the fire. The lodge lining was often finely painted with pictures of animals, people, and figures of mysterious beings that one might not speak about.

The seats and beds in this home were covered with soft, tanned buffalo robes, and at the head and foot of each bed was an inclined backrest of straight willow twigs, strung together on long lines of sinew and supported in an inclined position by a tripod. Buffalo robes often hung over these backrests. In the spaces between the the backrests, which, though they came together at the top, were separated at the ground, were kept many of the possessions of the family: the pipe, sacks of tobacco, of paint, “possible sacks” — parfleches for clothing or food, and many smaller articles.

The outside of the lodge was often painted with mysterious figures, which the lodge owner believed to have the power to bring good luck to him and his family. Sometimes, these figures represented animals — buffalo, deer, and elk — or rocks, mountains, trees, or the puff-balls that grow on the prairie. Sometimes, a procession of ravens, marching one after the other, was painted around the circumference of the lodge. The painting might show the tracks of animals or several water animals, apparently chasing each other around the lodge. On either side of the smoke hole at the top were two flaps or wings, each supported by a single pole. These were to regulate the draught of the fire in case of a change of wind, and the poles were moved from side to side, changing as the direction of the wind changed. On such wings were often painted groups of white disks representing some stars. At the back of the lodge, high up, just below the place where the lodge poles cross, was often a large round disk representing the Sun, and above that, a cross, which was the sign of the butterfly, the power that they believe brings sleep. From the ends of the wings, or tied to the tips of the poles which supported them, hung buffalo tails, and sometimes running down from one of these poles to the ground near the door was a string of the sheaths of buffalo hooflets, which rattled as it swung to and fro in the breeze.

Their arms were the bow and arrow, a short spear or lance, with a head of sharpened stone or bone, stone hammers with wooden handles, and knives made of bone or stone, and if of stone, lashed by rawhide or sinew to a split wooden handle.

The hammers were of two sorts: one quite heavy, almost like a sledgehammer or maul, and with a short handle; the other much lighter and with a longer, more limber handle. This last was used by men in war as a mace or war club, while the heavier hammer was used by women as an ax to break up fallen trees for firewood, like a hammer to drive tent-pins into the ground, to kill disabled animals, or to break up heavy bones for the marrow they contained.

These mauls and hammers were usually made by choosing an oval stone and pecking a groove about its shortest diameter. The handles were made by green sticks fitted as closely as possible into the groove, brought together, and lashed in position by sinew. The whole was then covered with wet rawhide, which was tightly fitted and sewed. As the rawhide dried, it shrunk and was strongly bound together with the parts of the weapon.

The Blackfoot bow was about four feet long. Its string was of twisted sinew, and it was backed with sinew. This gave the bow great power, so the arrow went with much force. The arrows were straight shoots of the serviceberry or cherry, and the manufacture of arrows was the chief employment of many of the men of middle life. Each arrow by the same maker was precisely like every other arrow he made. Each arrow maker tried hard to make good arrows. It was a fine thing to be known as a maker of good arrows.

The shoots for the arrow shafts were brought into the lodge, peeled, smoothed roughly, tied up in bundles, and hung up to dry. After they were dried, the bundles were taken down, and each shaft was smoothed and reduced to a proper thickness using a grooved piece of sandstone, which acted on the arrow-like sandpaper. After they were of the right thickness, they were straightened by bending with the hands and sometimes with the teeth. They were then passed through a circular hole drilled in a rib or in a mountain sheep’s horn, which acted in part as a gauge of the size and as a smoother, for if the arrow fitted tightly in passing through the hole, the shaft received a good polish.

The three grooves always found in the Blackfoot arrows were made by pushing the shaft through a round hole drilled in a rib, which had one or more projections left on the inside. These projections pressed into the softwood and made the grooves, which were in every arrow. The feathers were three in number. They were put on with glue, made by boiling scraps of dried rawhide, and held in place by sinew wrappings. The heads of the arrows were made of stone, bone, or horn. The flint points were often highly worked and very beautiful, being broken from larger flints by sharp blows of a stone hammer, and after they had been shaped, the edges were worked sharp by flaking with an implement of bone or horn. The points of horn or bone were ground sharp by rubbing on a stone. A notch was cut at the end of the arrow shaft, and the shank of the arrow point set in that. The arrowheads were firmly fixed to the shaft by glue and sinew wrapping.

Although the Blackfoot lived almost altogether on the flesh of birds or animals, they had some vegetable food. This was chiefly berries — of which in summer, the women collected great quantities and dried them for winter use — and roots, the gathering of which at the proper season of the year occupied much of the time of women and young girls. A long, sharp-pointed stick unearthed these roots called a root digger. Some roots were eaten as soon as collected, while others were dried and stored for winter.

After they reached the plains, the main food of the Blackfoot was the buffalo, which they killed in large numbers when everything went right. Many of the streams in the Blackfoot country run through wide, deep valleys bordered on either side by cliffs or broken precipices, falling sharply from the high prairie above. Long ago, the Blackfoot must have learned that it was possible to make the buffalo jump over these cliffs and that in the fall on the rocks below, numbers would be killed or crippled. No doubt, after this had been practiced for a time, there came to someone the idea of building at the foot of such a cliff where the buffalo were run over a fence that would form a corral or pound and which would hold all the buffalo that were jumped over the cliff. This corral they called piskun.

It is often said that the buffalo were driven over these precipices, but this is true only partly. Like most wild animals, buffalo are inquisitive. It was easy to excite their curiosity, and when they saw something they did not recognize, they were anxious to find out what it was.

When ran into the piskun, the buffalo were drawn by curiosity almost to the jumping point. Between two long diverging lines of people, who kept hidden until after the buffalo had passed them, they rose and showed themselves and tried to frighten the animals. Now, to be sure, for the short distance that remained between the place where they were alarmed and the place where they jumped, the buffalo were driven. Any attempt on the open prairie to drive buffalo in one direction or another would be certain to fail. The animals would go where they wished to. They would not be driven, though often they might be led.

To the people, the capture of food was the most important thing in life, and they made every effort to accomplish it. For this reason, the effort to capture buffalo was usually preceded by religious ceremonies, in which many prayers were offered to the powers of the earth, the sky, and the waters, many sacrifices were made, and sacred objects, like the buffalo stone, were displayed.

When the day for the hunt came, the man who was to bring the buffalo left the camp early in the morning, climbed the rocky bluffs to the high prairie, and journeyed toward some nearby herd of buffalo that had been located the day before by himself or by other young men. He approached the buffalo as nearly as he could without frightening them. Then, attracting the attention of some of the animals by uttering certain calls, he tossed into the air his buffalo robe or some smaller object. As soon as the buffalo began to look at him, he retreated slowly toward the piskun but continued to call and attract their attention by showing himself and then disappearing. Soon, some of the buffalo began to walk toward him, and others began to look and follow those that had first started so that before long, the herd of 50 or 100 animals might be walking or sometimes trotting after him. The more rapidly the buffalo came on, the faster the man ran — and sometimes it was a hard matter for him to keep ahead of the herd — until he had got far within the wings and near the cliff. Then, if there seemed danger that he would be overtaken, he watched his chance and either at some low place quickly dodged out of the line in which the buffalo were running or hid behind one of the piles of stones of which the wings were formed, or, if he had time, slipped over the rocky wall at the valley’s edge, to get out of the way of the approaching herd.

As soon as the buffalo had come well within the diverging lines of people who hid behind the piles of stones called wings, those whom the buffalo passed rose from their places of concealment, and by yells and shouts and the waving of their robes frightened the buffalo, so that they quite forgot their curiosity in the terror that now replaced it. Thus, when the leaders reached the cliff’s brink, they could not stop.

Those behind pushed them over, and most buffalo jumped over the cliff. Many were crippled or injured by the fall, and all were kept within the fence of the piskun below. About this fence, the people were collected. The buffalo raced round and round within the pen, the young and weak being injured or killed in the crowding, while above the fence, men were shooting them with arrows until presently all in the pen were dead or so hurt that the women could go into the pen and kill them. The people entered and took the flesh and hides.

Deer, elk, and antelope were shot with arrows, and antelope were often captured in pitfalls roofed with slender poles and covered with grass and earth. Such pitfalls were dug in a region where antelope were plenty, and a long-shaped pair of wings, made of poles or bushes or even rock piles, led to the pit. The antelope is very curious and was quickly led within the chute, and they were frightened, as were the buffalo, by people who had been concealed and who rose and showed themselves after the antelope had passed. This was done more to secure antelope skins for clothing than their flesh for food.

The Blackfoot did not eat fish and reptiles, nor were dogs, although many tribes of plains Indians eat dogs, wolves, and coyotes. Most small animals, and practically all birds, were eaten in case of need. In summer, when the wildfowl which bred on so many of the lakes in the Blackfoot country lost their flight feathers, during the molt, and again in the late summer, when the young ducks and geese were almost full-grown but could not yet fly, the Indians often went in large parties to the shallow lakes which here and there dotted the prairie, and, driving the birds to shore, killed them in large numbers.

When the fowl had begun to lay their eggs earlier in the season, these were collected in significant quantities for food. Sometimes, they were roasted in the hot ashes, but a more common way was to dig a deep, narrow hole in the ground in which the eggs were to be cooked. Several small platforms of small sticks or twigs were built in this hole, one above another, and they put the eggs on these platforms. Another much smaller hole was dug to one side of the large hole, slanting down into it. The large hole was partly filled with water and then roofed over by small sticks on which grass was covered with earth. Stones were heated in a fire built near at hand and then were rolled down the side hole into the larger hole, heating the water, which at last boiled and steamed, the steam cooking the eggs.

The Blackfoot were known as great warriors when the Americans first met them on the prairie. But up to the time they got from the Hudson Bay traders better weapons than they had before known; whether these were metal knives, steel arrow points, or guns, they probably did not do much fighting. There seems to have been no reason they should have fought unless they quarreled about small matters with other tribes. It became quite different when the Indians procured better arms and, above all when they got horses — a means of swiftly getting about over the country, something that all people wanted to have and which all were so eager to obtain that they would go into danger for them. In the old days of stone arrowheads, when they had to travel on foot and carry heavy loads on their backs, the whole thought and effort of the tribe must have been devoted to procuring a food supply.

The tribal and family life of the people was simple and friendly. The man and his wives loved each other and loved their children. Relationships counted for much in an Indian camp; cousins of remote degrees were called brother and sister. Children were not punished; they were trained by persuasion and advice. They were told by older people how they ought to act to make their lives happy and successful and be well thought of by their fellows. Young people had much respect for their elders, listened to what they said, and strove more or less successfully to follow their teachings.

The Blackfoot were very religious. They feared many natural powers and influences whose workings they did not understand, and they were constantly praying to the Sun — regarded as the ruler of the universe — as well as to those other powers which they believe live in the stars, the earth, the mountains, the animals, and the trees. The Blackfoot were constantly afraid that some evil might happen to him, and he prayed to all the powers for help — for good fortune in his undertakings, health, plenty, and a long life for himself and his family.

Among these tribes are several secret societies known as the All Comrades or All Friends — groups of men of different ages, alluded to in the stories. There were about 12 of these societies, but a number have been abandoned in recent years.

The tribe was divided into several clans, all of which were believed to be related. In old times, no member of a clan was permitted to marry another member of the clan, and relations might not marry.

In olden times, when large numbers of people were together, the lodges of the camp were pitched in a great circle, the opening toward the southeast. In this circle, each clan camped in its particular place in relation to the other clans. Within the circle was often a smaller circle of lodges, each occupied by one or more of the societies of the All Comrades. Many of the Blackfoot sometimes came together, perhaps even all of the three tribes, Blackfoot, Bloods, and Piegans. When this was the case, each tribe camped by itself with its circle, no matter how near it might be to one or other tribal circles.

We read of some tribes of Indians who believed that after death, the departed spirits went to a happy hunting ground where the game was always plenty and life was full of joy. The Blackfoot knew no such place as this. When they died, their spirits were believed to go to a barren, sandy region south of Saskatchewan called the Sand Hills. Here, as shadows, the ghosts lived a life much like their existence before death, but all was unreal — unsubstantial. Riding on shadow horses, they hunted shadow buffalo.

They lived in shadow camps, and dogs hauled their travois when they moved. Some stories tell that living people have seen these hunters, their houses, and their implements of the camp, but when the people got close, they found that what they thought they had seen was different. It reminds us a little of the old ballad of Alice Brand, where Urgan tells of the things seen in fairy-land:

“And gayly shines the Fairy-land —

But all is glistening show,

Like the idle gleam that December’s beam

It can dart on ice and snow.

“And fading, like that varied gleam,

Is our inconstant shape,

Who now like knight and lady seem,

And now like dwarf and ape.”

By George Bird Grinnell, 1913. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2024.

Also See:

The Blackfoot Indians – “Real” People of Montana

Blackfoot Vintage Photo Gallery

Myths & Legends of the Blackfoot

Native American Photo Galleries

About the Author-Article: Blackfoot Indians Stories was published by George Bird Grinnell in 1913 and is now in the public domain. George Bird Grinnell studied at Yale with an intense desire to be a naturalist. He talked his way onto a fossil-collecting expedition in 1870 and then served as the naturalist on Custer’s expedition to the Black Hills in 1874. Grinnell was interested in what he could learn from the Indian tribes of the region and, early on, was well known for his ability to get along with Indian elders. The Pawnee called him White Wolf and eventually adopted him into the tribe. Grinnell was also editor of Forest and Stream, the leading natural history magazine in North America, the founder of the Audubon Society and the Boone and Crockett Club, and an advisor to Theodore Roosevelt. Glacier National Park came about largely through his efforts. Grinnell also worked for fair and reasonable treaties with Native American tribes and preserving America’s wildlands and resources.