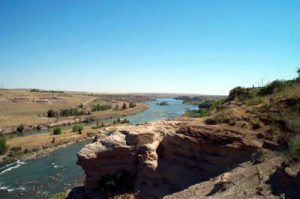

Containing a spectacular array of biological, geological, and historical objects of interest, the Upper Missouri River Break National Monument spans 149 miles of the Upper Missouri River, the adjacent Breaks country, and portions of Arrow Creek, Antelope Creek, and the Judith River. From Fort Benton, Montana to the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge, the monument includes six wilderness study areas, the Cow Creek Area of Critical Environmental Concern, segments of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail and the Nez Perce National Historic Trail, the Fort Benton National Historic Landmark, and more. The area was declared a National Monument in January 2001.

Though largely unchanged in the more than 200 years since Meriwether Lewis and William Clark traveled through it on their epic journey in 1805, the valley of the Upper Missouri River is a living museum, the product of many events over time. About 90 million years ago, wide oceans, volcanoes, and dinosaurs existed in Montana. Rivers continually carried sediment into the vast interior sea. These sediments of mud and silt were laid down in layers on the ocean floor. Over great periods of time, these sediments were compressed and formed into sedimentary rocks.

Next came the glaciers. They pushed south into present-day Montana and forced the Missouri River into a new channel by carving through stone and sediment to re-route the flowing waters. As more time passed, flowing magma from prehistoric volcanoes hardened and formed into igneous rock while uplifts occurred on the ocean floor, causing the interior seaway to drain. These newly exposed landforms have been subjected to rain, snow, wind, ice, and piercing heat. These climatic forces shaped the sedimentary and igneous rocks into extraordinary cliffs, canyons, pillars, and spires near the water’s edge creating the landform known as the Breaks. The black color of old volcanic features contrasts sharply with the lighter-colored shale’s and sandstones creating beautiful views.

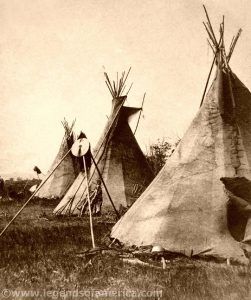

For thousands of years, the Upper Missouri River area provided a home for many Native American tribes such as the Blackfeet, Gros Ventre, Assiniboine, and Crow. Other tribes, including the Shoshone, Cheyenne, Sioux, and Nez Perce, traveled through and used the area. Though sparse in appearance, the Missouri River landscape provided many resources the tribes needed for daily living, including numerous types of plant and animal life. These tribes lived by following the tremendous herds of bison as the animals roamed the prairie. Other game species, such as elk and deer, also provided sustenance. Plants along the Missouri River, such as willow and snowberry, provided for and supplemented their nutritional and medicinal needs. These first peoples utilized the Missouri River as a path of trade and transport. In addition, the river and its tributaries formed tribal boundaries.

The center of Native American trade along the Missouri River was in the Dakotas region on its great bend. Here, a large cluster of walled Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara villages situated on bluffs and islands was home to thousands of people and would later serve as a market and trading post used by early French and British explorers and fur traders.

The first Europeans encountered the river in the late 17th century. The region passed through Spanish and French hands before finally becoming part of the United States through the Louisiana Purchase. Following the introduction of horses to Missouri River tribes, the natives’ way of life changed dramatically. The use of the horse allowed them to travel greater distances and thus facilitated hunting, communications, and trade.

As a route of western expansion, the Missouri River had few equals. From May 24 through June 13, 1805, Lewis and Clark spent three weeks exploring the segment that is now the Upper Missouri National Wild and Scenic River. Today this portion is considered the premier component of the Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail. Captain William Clark wrote about the badlands saying,

“This country may with propriety, I think, be termed the Deserts of America, as I do not conceive any part can ever be settled, as it is deficient in water, timber, and too steep to be tilled.” On May 31, 1805, the Corps camped at Stonewall Creek (present-day Eagle Creek), where Lewis remarked in his journal about the sandstone white cliffs along the river. “The hills and river cliffs, which we passed today exhibit a most romantic appearance …” and described “… elegant ranges of lofty freestone buildings, having their parapets well stocked with statuary …” and “… scenes of visionary enchantment…”

On June 2, 1805, the Corps reached the Missouri River’s confluence with another river that they named Maria’s River, in honor of Lewis’s cousin (today the river is called Marias, pronounced as Mah-rye-us). At this point, they had to decide which river was the true Missouri. Therefore, the site, near Loma, Montana, is known as Decision Point. On June 3, Lewis wrote in his journal:

“This morning early, we passed over and formed a camp on the point formed by the junction of the two large rivers… An interesting question was now to be determined; which of these rivers was the Missouri… Capt. C & myself strolled out to the top of the heights in the fork of these rivers from whence we had an extensive and most enchanting view; the country in every direction around us was one vast plain in which innumerable herds of buffalo were seen attended by their shepherds the wolves; the solitary antelope which now had their young were distributed over its face; some herds of Elk were also seen; the verdure perfectly clothed the ground, the weather was pleasant and fair…”

They spent days at the mouth of the Marias River trying to resolve the dilemma of which river to follow. Through exploration, river observations, and the captains’ educational background, Lewis and Clark determined in slightly more than a week which river was the correct one and therefore, which route to take. They took the southern route. This decision took the explorers in the right direction as they continued to the Pacific Ocean.

During the years following the Lewis and Clark Expedition passage, the Blackfeet Indians showed such an uncompromising hatred for Europeans that the tribe effectively prevented the penetration of their territory by trappers. However, the American Fur Company was finally successful in opening the upper river to trade in 1831. That year, they established Fort Piegan at the mouth of the Marias River. The following year they moved eight miles upriver and established Fort McKenzie. The Missouri River soon became one of the main westward expansion routes, with the fur trade’s growth laying much of the groundwork as trappers explored the region and blazed trails. Pioneers headed west en masse beginning in the 1830s, first by covered wagon, then by the growing numbers of steamboats entering service on the river. Former Native American lands in the watershed were taken over by settlers, leading to some of the most longstanding and violent wars against indigenous peoples in American History.

A Swiss painter named Karl Bodmer was asked to journey across the American West in 1832 with German Prince Maximilian of Weid. They reached St. Louis, Missouri, in March 1833 and traveled into the American frontier on the steamboat Yellowstone, owned by the American Fur Company. They had traveled nearly 1,500 miles in seven weeks and stopped at Fort Pierre, South Dakota. They traveled another 500 miles on the steamboat Assiniboine to Fort Union, North Dakota, then on a keelboat to Fort McKenzie, a site about seven miles downstream from present-day Fort Benton.

Prince Maximilian was fascinated by Native American culture, and he, Bodmer, and their entourage spent more than a month in the area. After a large force of Assiniboine and Cree attacked the fort, Maximilian and his group decided to return east, wintering at Fort Clark, North Dakota. In May 1834, the party arrived in St. Louis, then traveled to New York City, and finally back to Europe. Bodmer created 81 paintings to illustrate the journey in the American West. His work captures images of many native peoples, including their apparel, cultural ceremonies, and material possessions. Bodmer’s other significant paintings included breath-taking landscapes, such as the sculpted rock formations of the White Cliffs and Citadel Rock that sit along the Missouri River. Much of the landscape he captured still looks the same today as when he and Prince Maximilian traveled through.

In 1844, Fort McKenzie was abandoned by the American Fur Company, operations were moved downriver to the mouth of the Judith River, and Fort Chardon was established. In 1845, Fort Chardon was abandoned, and Fort Lewis was established a few miles above the future site of Fort Benton. In 1846, Fort Lewis was abandoned. They moved a few miles downriver and established Fort Clay, which would be renamed Fort Benton in honor of Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, a strong political supporter of the fur trade. In the same year the post was established, Catholic missionaries Father Pierre-Jean de Smet and Father Nicholas Point celebrated Mass for the Flathead and Blackfeet tribes to soothe relations between these traditional enemies at the Judith and Missouri Rivers.

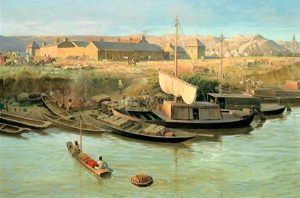

Called the birthplace of Montana, Fort Benton would thrive as a center of commerce. Here the Indians and white fur traders alike exchanged their pelts and hides for clothing, arms, liquor, and other items. The fur trade era stimulated the first extensive use of the Missouri River as an avenue of transportation. Keelboats, mackinaws, bull boats, and canoes plied the upper river bringing trade items and returning with a wealth of furs and buffalo robes. The vast amount of capital to be obtained encouraged steamboat captains to brave the treacherous Missouri River. Steamboat navigation on the Missouri River started in 1831 when the steamer Yellowstone reached Pierre, South Dakota. The following year it got to Fort Union, North Dakota, on the present eastern boundary of Montana.

In 1855, Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens conducted a treaty council with the Blackfeet, Flathead, Gros Ventre, and Nez Perce. This treaty established boundaries and provided railroads, roads, telegraph lines, and military post access across northern Montana.

Several other upstream efforts were made, and in 1859, Captain John LaBarge, accompanied by Charles Chouteau of the American Fur Company, attempted to reach Fort Benton. They fell only 12 1/2 miles short of their goal, unloading the Chippewa at the former site of Fort McKenzie. The following year they were successful. On July 2, 1860, the steamer Chippewa, followed closely by the Key West, reached Fort Benton and proved that the channel of the Missouri River was navigable to that point. Navigability was established just in time to serve the gold camps, which were about to open in southwestern Montana.

Discoveries of gold in 1862 at Grasshopper Creek, in 1863 at Alder Gulch, and in 1864 at Last Chance Gulch put an entirely new picture on the development of Montana. The era of the fur trade was passing. The era of mining was beginning. River traffic became heavy as steamboats brought men and supplies to the goldfields and returned downriver with products. In 1866, for example, Grant Marsh pointed the Luella downriver with a cargo of 2 1/2 tons of Confederate Gulch gold dust. It was valued at $1,250,000 and was the wealthiest cargo to go down the Missouri River.

Business in Fort Benton was booming. Almost as exciting as the river traffic which brought commodities into Fort Benton was the transportation industry, which carried the merchandise out. Stage lines, bull trains, mule trains, and similar transportation methods were available for the commodities destined for points beyond Fort Benton. “All trails lead out of Fort Benton” was a familiar statement. The community was the anchor of the Mullan Road to Fort Walla Walla in present-day Washington. The Fisk Wagon Road to St. Paul, Minnesota, through northern Montana and North Dakota, was another. The road to Helena and other gold mining towns branched off Mullan Road. The Whoop-Up Trail led into Canada and was an important factor in keeping Fort Benton prosperous.

In the meantime, the Homestead Act was passed in 1862, which gave Americans title to 160 acres of undeveloped land west of the Mississippi River. The law required homesteaders to apply, improve the land, and file for a deed of title. Much of the prime land, especially near or along waterways, including the Missouri River, became settled.

In 1877, the non-treaty Nez Perce tribe fled their homelands from the U.S. Army in Idaho across Montana toward Canada. They crossed the Upper Missouri River at Cow Island, approximately 126 miles below Fort Benton. They attempted to trade for supplies, but the soldiers denied their requests, so the Indians spent extra time to forcibly take the supplies and rest. This delay of 24 precious hours impacted the outcome for the non-treaty Nez Perce at the Bear Paw Battlefield. Forty miles short of the Canadian border and following a five-day battle and siege, the Nez Perce ceased fighting at Bear Paw on October 5, 1877, in which Chief Joseph gave his immortal speech: “From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

During the 1880s, river traffic began to drop as the newly built railroads cut into the market. Driving the silver spike in Fort Benton in September 1877 signaled the end of the great steamboat era. The last commercial boat unloaded its cargo in 1890. By then, the buffalo had disappeared from the plains to be replaced by livestock. Fort Benton changed from a raucous river port to an agricultural supply center.

In 1909 Congress enacted another homesteading law called the Enlarged Homestead Act. This law targeted land suitable for dryland farming and increased the number of acres to 320. In 1916, the Stock-Raising Homestead Act targeted settlers seeking 640 acres of public land for ranching purposes.

The 19th-century farmer on the Great Plains was an important part of the food production chain. To get their products to market, they depended on the efforts of many people. The farmer was, however, even more dependent on nature. The unpredictable weather of the Great Plains, specifically the Missouri River Breaks area, tested the resolve of many people trying to earn a living on the landscape. However, homesteaders began arriving in large numbers around 1910. Climate, lack of water, and poor soil plagued the homesteaders, and within a few years, the majority of the landscape belonged to large ranchers who didn’t depend upon crops to make a living. Several historic structures still stand within the Missouri Breaks National Monument, testifying to the region’s homesteading history.

During the 20th century, the Missouri River basin was extensively developed for irrigation, flood control, and hydroelectric power generation. Fifteen dams impound the river’s main stem, with hundreds more on tributaries. Meanders have been cut, and the river channelized to improve navigation, reducing its length by almost 200 miles from pre-development times. Although the lower Missouri Valley is now a populous and highly productive agricultural and industrial region, heavy development has taken its toll on wildlife and fish populations and water quality.

In 1976, Congress designated a 149-mile stretch of the Missouri River through north-central Montana as wild and scenic. In 2001, President Clinton established the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument.

In addition to its rich history and widely contrasting scenes, visitors can also float the river, fish, hike, hunt, and camp within the monument.

More Information:

Upper Missouri River Breaks Interpretive Center

701 7th Street

Fort Benton, MT 59442

406-622-4000

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated July 2022..

Also See:

Corps of Discovery – The Lewis & Clark Expedition

Fort Benton – Birthplace of Montana

Sources:

Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument

Wikipedia – Missouri River