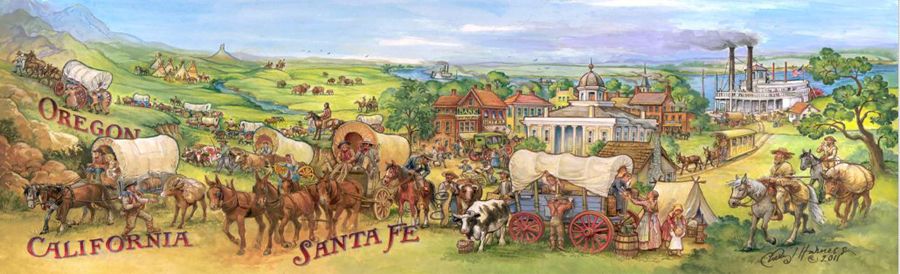

Trails Leaving Independence by Charles Goslin mural hangs in the National Trails Museum in Independence, Missouri.

Old Franklin & the Start of the Santa Fe Trail

Arrow Rock & the Santa Fe Trade

Independence – Queen City of the Trails

Westport (Kansas City)

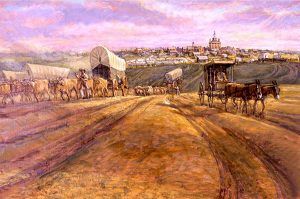

“Noise and confusion reigned…Traders, trappers, and emigrants filled the streets and stores. All were in a hurry, jostling one another and impatient to get through with their business. The salesmen were overworked, but good nature aided them in preserving their tempers. Mules and oxen strove for the right of way. ‘Whoa’ and ‘haw’ resounded on every side, while the loud cracking of ox goads, squeaking of wheels, and rattling of chains, mingled with the oaths of teamsters, produced a din indescribable.”

– William G. Johnson, Independence, Missouri, April 12, 1849

The Santa Fe Trail was important in the early history of the State of Missouri. The state has been a United States territory since 1812 and attained statehood in 1821; therefore, unlike the other four states along the trail, Missouri was already a state when the trail opened. The trail and the trade with Mexico provided a much-needed boost to, and continuing support of, the young state’s economy. New settlements were formed and developed as outfitting points for the trail, and existing settlements, such as St. Louis, expanded and grew wealthy on the profits made from the trade.

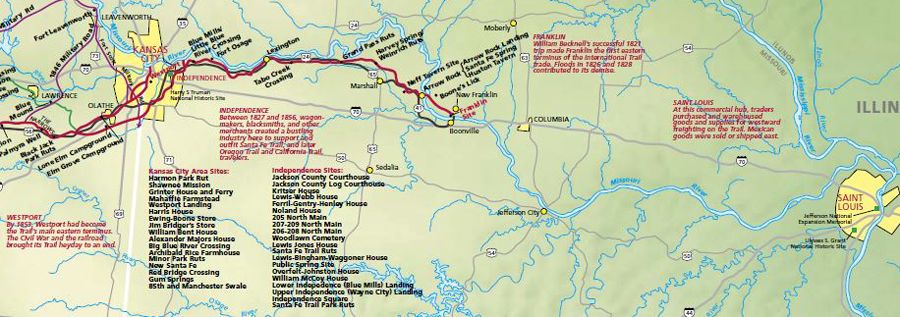

The Santa Fe Trail crossed the western portion of Missouri, generally following the Missouri River. As measured from Franklin in the central part of the state to the state line, 130 miles. The Osage Trace, a secondary route of the Santa Fe Trail, ran between the Arrow Rock Ferry and Fort Osage. Boone’s Lick Trail connected St. Louis with the Franklin area. Missouri towns, trails, and rivers linked the Santa Fe Trail and the eastern U.S. cities, merchants, and ports.

Before European incursions and settlement, seven principal Indian tribes resided in what became the State of Missouri. The two tribes claiming the majority of land in the state were the Missouria, located north of the Missouri River, and the Osage, south of the river. Other tribes in the state included the Ioway and the Sac and Fox, who claimed lands extending a short distance into north-central Missouri, and the Otoe were found in Atchison County, in the extreme northwest corner. Kanza tribal land crossed the Missouri River into western Missouri north of the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers (in modern Kansas City).

The land contained within the boundaries of Missouri had, at various times, been claimed by France and Spain. Spanish claims to the Mississippi River Valley stemmed from the 1542 explorations of Hernando de Soto. France claimed the Mississippi River Basin in 1682 for King Louis XIV, based on Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet’s explorations in 1673. French Canadian woodsmen and voyageurs traveled wilderness trails and rivers during the 17th and 18th centuries, trading with Indian inhabitants and trapping fur-bearing animals.

The United States acquired Missouri through the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. The newly acquired lands were divided into the Territory of Orleans, which later became the state of Louisiana, and the District of Louisiana, which was initially placed under the jurisdiction of the Territory of Indiana. On March 2, 1805, Congress changed the District of Louisiana to the Territory of Louisiana.

In 1805, St. Louis, an important trading hub, became the government seat for the new territory encompassing the southern half of the former Louisiana Purchase lands. St. Louis was already a significant outpost for the fur trade when it became part of the United States. After 1804, the fur trade expanded under U.S. control, and settlements began to be established along the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. On May 14, 1804, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark began their exploration journey from St. Louis, traveling up the Missouri River and onto the Pacific Ocean. The Lewis and Clark expedition returned to St. Louis on September 23, 1806.

In 1808, Fort Osage was established to trade with the Osage Indians, who in September of that year inequitably ceded most of their land in Missouri and Arkansas – some 30 million acres – in return for $1200 worth of gifts, an annuity of $500, and services of a blacksmith and grist mill at the fort. Fort Osage was one of 28 government Indian “factories” (trading posts) that operated between 1796 and 1822 as part of the government factory system, which attempted to control trade with the tribes. Under the command of William Clark, the U.S. Infantry and Territorial Militia built the post strategically on the Missouri River. Fort Osage became an important location in the fur trade, collecting furs and pelts that were then shipped down the Missouri River to St. Louis. Until it ceased in 1827 to be an active post and military storage facility, Fort Osage also served as a convenient rendezvous for trappers, mountain men, explorers, and, later, traders in the early years of the Santa Fe trade. Fort Osage was the site from which the 1825 Sibley Survey of the Santa Fe Trail embarked.

By the Territory of Missouri Act of June 4, 1812, the Territory of Louisiana became the Territory of Missouri to avoid confusion with the newly formed State of Louisiana. Under this Organic Act, Missouri Territory was divided into five counties, and President James Madison appointed a governor. Benjamin Howard served as the first governor until his resignation in July 1813. At that time, William Clark was appointed to the position, which he held until 1821 when Missouri became a state.

On June 18, 1812, the United States declared war on Britain. Hostility toward the British ran hotly in Missouri. The American inhabitants were particularly angry about British traders providing weapons for Indian tribes and inciting them. As a result, many settlers in central Missouri moved east during the war. In the expectation of Indian attacks, Missourians built a series of stockade posts along the Mississippi River frontier. The war between the U.S. and Britain ended on December 24, 1814, with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent. The end of the war and the signing of the treaty resulted in a steady decrease in warfare between the British and Americans; however, the U.S. government did not immediately make peace with the Indian nations, so hostilities between Indians and Missourians continued. Not until 1816, after the signing of peace treaties with several tribes, was immigration to Missouri renewed.

The first few years of the 1820s were significant for Missouri. A stagecoach line was established in 1820, linking St. Louis to Franklin (organized in 1816) in Howard County. This stage line helped to increase the number of people in central Missouri. That same year, the U.S. Congress finalized the first Missouri Compromise. This agreement stated that to maintain the balance of free and slave states, the admission of a new pro-slavery state required the admission of a new free state. Maine, a free state, became the 23rd state, and pro-slavery Missouri was the 24th. On August 10, 1821, President Monroe admitted Missouri, with its pro-slavery constitution, into the Union. In 1821, François and Bérénice Chouteau traveled up the Missouri River to a point near the Kansas River’s confluence and established a new trading post. On June 2, 1825, Treaty with the Osage Indians, the tribe ceded their remaining lands in western Missouri, which opened the way for increased settlement.

The same year Missouri became a state, Mexico gained its independence from Spain, and legal trade between the United States and Mexico began. The profits made by Captain William Becknell’s first trading trip brought much-needed money and valuable goods into central Missouri, where the Panic of 1819 devastated the economy. This economic depression was caused, in large part, by a short supply of money. With no banking system, paper money was considered worthless in Missouri, so only gold and silver coins were accepted as payment. No markets existed for farmers to sell their produce or for merchants to peddle their wares, and many people were in debt. The influx of Mexican coins significantly helped Missouri’s economy as farmers and local merchants found a new market for their goods. The advent of legal trade with Mexico promised to counteract the effects of the economic panic in Missouri.

The gold and silver coins brought into the state by Becknell’s expedition from Mexico spurred additional trade along two previously established Missouri trails: the Boone’s Lick Trail and the Osage Trace. Travelers and traders followed the Boone’s Lick Trail from the Mississippi River in the St. Louis vicinity overland to Franklin, Missouri. The river west of Franklin was then crossed by ferry at Arrow Rock – a landmark where the town of Arrow Rock was founded in 1829. From Arrow Rock, the Osage Trace provided an overland route to Fort Osage, approximately 100 miles west. The trace was created soon after Fort Osage was established in 1808 and followed the south side of the Missouri River. The river was often muddy in the spring, and several tributaries had to be crossed. From Fort Osage, travelers followed the Santa Fe Trail to Santa Fe and Chihuahua, Mexico. With direct access to St. Louis and Fort Osage, Franklin became an important regional trading center, albeit only briefly. Becknell’s 1821 expedition left from the Franklin area, and soon after his successful trip, ferry traffic in the region increased, hauling U.S. and Mexican traders heading to and from Santa Fe.

In the decade up to 1821, Missourians began utilizing the Missouri River to transport trade goods from St. Louis into central Missouri. The first boats on the Missouri River were ferries, but steamboats slowly followed these. On August 2, 1817, the first steamboat, the Zebulon M. Pike, arrived at St. Louis – nearly two years before a steamboat, the Independence, made it up the Missouri River to Franklin. This increased travel and trade along the Missouri River’s lower portion.

Steamboats became the preferred means of transportation in the late 1820s, and as a result, the eastern terminus of the Santa Fe Trail moved west. Before 1826, there were virtually no civilian steamboats maneuvering the river. Central Missouri towns along the Missouri River, navigable between March and November, provided the perfect eastern termini for the Santa Fe Trail. Merchandise for the trade could be brought in from St. Louis by riverboat at lower rates than overland routes. In the 1820s, the Arrow Rock ferry was heavily used by Euro-American traders, leaving Franklin bound for Santa Fe and Mexican merchants heading to Franklin. Until 1827, some travelers may have used the landing at Fort Osage near Sibley, Missouri.

With the establishment of Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in May 1827, a new steamboat landing was available for military freight, which could then be transported along the Santa Fe Trail via a military trail. By 1830, new river towns with steamboat landings had been established along the Missouri River between Arrow Rock and Fort Leavenworth, including Arrow Rock, Glasgow, Chariton, Brunswick, Lexington, Liberty, and Independence. Above the Kansas River, Fort Leavenworth was the only landing related to the Santa Fe Trail. The various trailhead towns and St. Louis all experienced rapid growth in part due to providing for the needs of traders and travelers on the Santa Fe, Oregon, and California Trails. Travelers needed supplies for the journey across the plains, including fresh livestock, food, camp supplies, and some trinkets for trading with Indians encountered along the way. As a result of this demand for supplies, various stores, warehouses, freight company offices, and homes were built in Missouri trail towns to outfit Santa Fe traders and other travelers. Traders needed access to manufactured goods for trade from cities on the East Coast and imports from European markets that were possible from St. Louis.

Steamboat landings near the Missouri River’s big bend in Jackson County, Missouri, offered the greatest advantage to traders. By freighting goods farther on the river, nearly 100 miles of unimproved and often muddy roads could be avoided. Independence was platted in Jackson County in 1827, a few miles southwest of the Blue Mills Landing and southeast of the Independence Landing. For two decades after that, it served as the principal eastern trailhead and outfitting point for the Santa Fe trade. The new town soon boasted several settlers and a store run by James Aull. In 1832, Westport Landing was established on the Missouri River, a short distance east of the Kansas River’s confluence, on the site of present-day Kansas City, Missouri. The Chouteau trading post, established in 1821, flooded out in 1830 and was moved to Westport Landing.

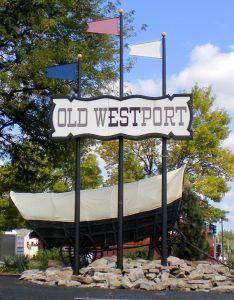

Old Westport, Missouri, Wikipedia

In 1833, John Calvin McCoy established a store focused on trading with Indians west of Missouri in what later became Kansas Territory. On February 13, 1835, McCoy platted the Town of Westport about four miles south of the landing, and over the next few years, he significantly improved the trail leading from Westport Landing to Westport. Westport Landing was acquired by the Kansas Town Company, of which McCoy was a member, in 1838. With a better river landing than Independence, some traders began stopping at Westport Landing and using Westport as an outfitting point by about 1840. By the mid-1840s, trail traffic, using Westport as an outfitting point and trailhead, had caught up and possibly exceeded Independence. Westport’s growth as an outfitting point can be partially attributed to the Mexican traders that stopped here en route from Santa Fe. Compared to Independence, the landscape of the Westport area offered better areas for herds to graze and water. At the same time, these traders awaited the arrival of their goods purchased in the eastern United States to arrive at the various river landings. To accommodate the travelers themselves, outfitting operations opened in Westport. In 1846, McCoy drew the first plat map of the Town of Kansas (including Westport Landing), which became an official municipality in 1850. By this time, the town was developing into a significant place. Kansas City’s location on the Missouri River’s elbow gave the town an advantage over inland trailheads such as Independence and supply points such as Westport, making it a substantial terminus for the Santa Fe Trail.

With the establishment of new Missouri River landings and trailhead towns in the greater Kansas City area, the Santa Fe Trail evolved to follow three main alternate routes. These routes depended on which river landing and trailhead were used and where the Big Blue River was crossed. This tributary of the Missouri River was the major impediment to travel through Jackson County because of its steep banks. When most traders used pack animals in the early years of the trail, there were several possible Big Blue crossings. The lower crossing, less frequented than the upper crossing, was located in modern-day Swope Park near 73rd Street. The upper crossing was near the Missouri-Kansas state line, just north of the Jackson-Cass county line, 18 miles south of the Kansas River, and about four miles south of the later town of New Santa Fe.

“It is to this beautiful spot, already grown up to be a thriving town, that the prairie adventurer, whether in search of wealth, health, or amusement, [comes], about May 1…they purchase their provisions for the road, and many of their mules, oxen, and even some of their wagons — in short, load all their vehicles, and make their final preparations for a journey across the prairie wilderness.”

— Commerce of the Prairies, Josiah Gregg, 1844

Two early routes existed in the 1820s before the three main routes were frequented. One early route left from Fort Osage, heading southwest, passing southeast of the later location of Independence. This route crossed the Big Blue River at the lower crossing. It continued west across the Missouri border approximately nine miles south of the Missouri River, passing Round Grove (later Lone Elm) near modern 167th and Lone Elm Road in Johnson County, Kansas. The other early Santa Fe Trail route through the Kansas City area left from Blue Spring some 12 miles south of Fort Osage on Harmony Road, the generally north-south road between Fort Osage and Harmony Mission to the Osage Indians. Traders followed this mission road several miles south before heading southwest along the high ground. The route then crossed the Big Blue River at the upper crossing. These two early routes converged near present-day Gardner, Kansas.

The three major routes through Kansas City were the Blue Spring Route, the Independence Route, and the Westport Route. The easternmost route was the Blue Spring Route. This left the Missouri River at Fort Osage and traveled south-southwest, passing the east side of Raytown. It then crossed the Big Blue River at the upper crossing and the Missouri-Kansas state line south of New Santa Fe before joining the eastern Kansas trail. To the west of this route was the Independence Route, which carried most traffic. Typically leaving the Missouri River at Independence Landing, traders passed through Independence Square, Minor Park in Kansas City, and New Santa Fe, Missouri, before joining the trail near Gardner, Kansas. The westernmost of the three major routes was the Westport Route, which avoided the Big Blue River by leaving the river west of the Big Blue River’s mouth. Merchandise was off-loaded from steamboats at Westport Landing, and traders headed south-southwest, crossing the Missouri border nine miles south of the Missouri River and continuing west to modern Olathe, Kansas. The Westport Route joined the other routes near Gardner in Johnson County, Kansas. The eastern trail routes from Blue Spring and Fort Osage were used and modified up to about 1840. After 1828, more traffic bypassed Blue Spring and left from Independence; however, traffic continued south of Independence and crossed the Big Blue at the upper crossing. This route was shortened by about 1839 when the Red Bridge crossing of the Big Blue, near modern Red Bridge Road in southern Kansas City, Missouri, replaced the upper crossing.

Until the railroad reached western Missouri in the late 1850s, Kansas City remained the major eastern terminus for the Santa Fe Trail. The Union Pacific Railroad – Missouri’s first – arrived in St. Louis in 1851; by February 1859, the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad had reached St. Joseph, Missouri. At the outbreak of the Civil War, the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad was the only line completed across Missouri. After the war, Missouri saw a boom in railroad construction, with the Pacific Railroad reaching Kansas City in 1865. Shortly after the railroad reached the trailhead towns of Independence, Westport, and Kansas City, the trail’s eastern terminus continued to move westward into Kansas and Colorado, ending Missouri’s major role in the Santa Fe trade. However, portions of the trail were converted into public roadways soon after leaving Missouri.

Several modern roadbeds overlay portions of the Santa Fe Trail system in the Kansas City Area. These include Westport Road as it leaves Independence Square, heading southwest until it hits Blue Ridge Boulevard. At this junction, the Blue Ridge Cutoff heads south to the Rice-Tremonti house at present-day E 66th Street. The Rice-Tremonti house is also where the Santa Fe Trail’s main branch reunites with the cutoff as present-day Blue Ridge Boulevard. The boulevard follows the trail south and east to this location from approximately where it intersects with I-70 and US-40 Hwy in eastern Kansas City until E 83rd Street in southern Raytown. Portions of Broadway Boulevard, Westport Road, US-40 Hwy, and other minor streets in the Kansas City area were also portions of the Santa Fe Trail.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

Independence – Queen City of the Trails

Santa Fe Trail – Pathway to the Southwest

Sources: See Santa Fe Trail Site Map & Writing Credits