The Kennecott Mines and mill town are an abandoned copper mine operation and ghost town in Alaska that, together, form a National Historic Landmark District. Located within the Wrangell-St. Elias National Park & Preserve, this historic site, tells a story of discovery, perseverance, and ingenuity at a time when America was hungry for copper to build railroads, electrify cities and supply munitions to the WWI effort. Kennecott helped meet America’s copper challenge and, in the process, transformed itself from a tiny mountain mining town into a large transnational minerals corporation.

It all began in the summer of 1900 when prospectors Clarence Warner and “Tarantula” Jack Smith were exploring the east edge of the Kennicott Glacier. There, they found a large outcropping of exposed copper. When they had the ore assayed, it revealed up to 70% pure chalcocite, one of the richest copper deposits ever found.

On July 4, 1900, the two prospectors filed a claim on what they called the Bonanza Mine. By mid-August, the two men and nine partners had staked much of the ground, which would later become known as the Kennecott mines.

A young mining engineer, Stephen Birch, who was in the area looking for investment opportunities for the wealthy Havemeyer family, began buying up shares of the Bonanza claim. However, it was worthless without a way to transport the copper to market. Some said building a railroad from the coast, across mountains, powerful rivers, and moving glaciers would be impossible. Others offered a glimmer of hope.

Backed by Henry O. Havemeyer, a New York capitalist, Birch formed the Alaska Copper and Coal Company which was promptly sued by others claiming ownership of the deposit. From 1901 to 1904, the Chitina Exploration Company, which claimed to have grubstaked the prospectors, and the Copper River Mining Company, which claimed the legal title, dragged the suit through territorial and federal courts. However, in the end, they lost, and the United States Supreme Court refused to hear the case.

In 1905 the Alaska Copper and Coal Company was reorganized as the Kennecott Mines Company. The Guggenheim family, controllers of the American Smelting & Refining Company (ASARCO) smelter monopoly, and J.P. Morgan, another wealthy industrial investor, entered the enterprise and organized the “Alaska Syndicate” to fund the mine’s development.

In the fall of 1907, the Alaska Syndicate hired Michael J. Heney, the White Pass & Yukon Railroad builder. His crews worked relentlessly for the next four years, building rail beds and bridges through rugged terrain at temperatures down to 40 degrees below zero. At the same time, Stephen Birch was in Kennecott developing the mining claims. By hauling an entire steamship, piece by piece, over the mountains from Valdez to be reassembled on the Copper River, he was able to bring equipment in by dog sled, horse, and steamship to begin mining ore even before the railroad was finished.

Between 1905 and 1911, the syndicate spent $25 million to build the mine and mill works, the 196-mile railroad and organized a steamship line that connected the copper port of Cordova, Alaska, with ASARCO’s Tacoma, Washington smelter. All this occurred before the first shipment of copper.

On April 8, 1911, the first trainload of copper, worth $250,000, was shipped from Kennecott in 32 railroad cars. By 1916 production had reached 108,372,783 pounds of copper worth $28,042,396. Kennecott was among the nation’s largest mines, with those at Butte, Montana, Bisbee, Arizona, and Bingham Canyon, Utah.

During 1915-1922 it ranked 3rd to 7th in production of all the mines in the nation. With the building and operation of the mines and their supply line — the Copper River and Northwestern Railway — this was the most extensive, costly, and complex mining enterprise ever established in Alaska. But Kennecott’s significance lies more in the quality of ore. Despite the general assumption that Alaska’s gold was preeminent, no Alaskan placer gold district or gold lode entity was as productive in mineral wealth as the Kennecott.

On April 12, 1915, the Kennecott Copper Corporation was formed by the Guggenheim and Morgan interests. Stephen Birch became the first president and saw the transfer of the Alaska Syndicate holdings to the Kennecott Mines Company, including the Copper River and Northwestern Railway, the Alaska Steamship Company, and the Beatson Copper Company. The phenomenal profits from the Alaska mine provided the capital to fund Kennecott’s purchase of the Bingham Canyon Mine in Utah and the Utah Copper Company, the Braden Copper Company, and other low-grade mines in Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico.

By the 1930s, while the deposit in Alaska was nearing exhaustion, the corporation had expanded to become the nation’s largest copper company and an international force in the metals market. The Kennecott business organization had met the shifting realities of the mining world. The Kennecott deposit, though rich, proved limited in extent. The operation closed in 1938 after producing an estimated $200 to 300 million worth of copper in 28 years. It then vacated the camp and donated its railroad to the territory.

At the peak of operation, approximately 300 people worked in the mill town and 200-300 in the mines. Kennecott was a self-contained company town with a hospital, general store, school, skating rink, tennis court, recreation hall, and dairy.

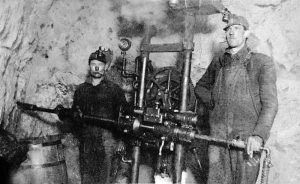

While the mines were operating, Kennecott was a place of long hours and hard, dangerous work. About 600 men worked in the mines and mill town at the height of operation. Paying salaries higher than those found in the lower 48 states, Kennecott attracted men willing to live and work in this remote Alaskan mining camp. Miners often worked seven days a week, coming down only for the rare holiday or to leave Kennecott. Mill workers and miners came to Kennecott only to work, living in bunkhouses with little time off, often sending money home to their families around the world.

While Kennecott was primarily a place of work, ensuring a thriving community social life was good for the company’s profit margin, leading to stronger employee retention and lower training and transportation costs. Movie and dance nights in the Recreation Hall were a time of relaxation and social gathering. Other amusements centered around skating or sledding during the winter and baseball during the summer. Fourth of July and Christmas celebrations in McCarthy marked special events. Hunting and fishing absorbed what little free time existed.

In June of 1998, the National Park Service acquired many significant buildings and lands of the Kennecott Mines National Historic Landmark and began the effort to stabilize and restore the buildings.

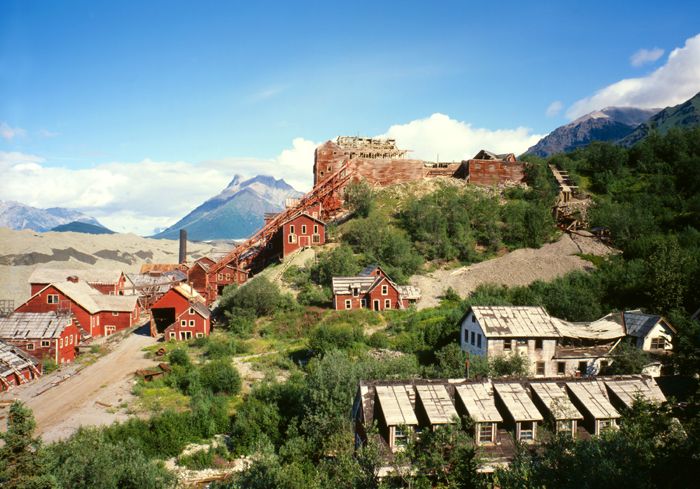

Today, the mining camp is little changed since the 1938 closing and provides visitors with a window into the technology and work environment of the early 20th century. Technological artifacts remain in situ due to the site’s remoteness.

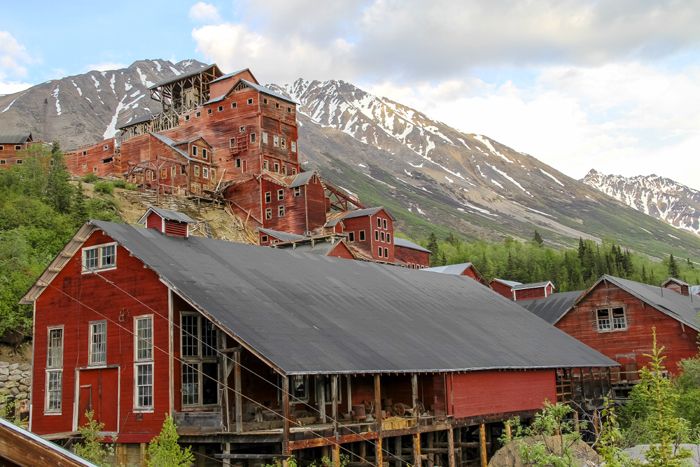

The central industrial zone of the Kennecott mill town includes the concentration mill and its associated structures. The 14-story wood frame mill, with its many gables and dormers, its location on the slope above the railroad grade, and its many chutes and bins, is the dominant structure at Kennecott. In it worked half of the employees of the camp. The concentrator contains all of its original machinery: two Buchanon jaw crushers, a Stevens-Adamson Apron Feeder, a Symons Crusher, Hancock Jigs, Colorado Impact Screens, Wilfley tables, a Door Thickener, ore bins, and sackers. The concentrator is an excellent reminder of turn-of-the-century mining technology and working conditions in Western training camps.

The plant, the world’s first commercial ammonia leaching plant, went into operation in 1916. It allowed the recovery of a high percentage of copper ore from formerly considered waste rock. The leaching plant was enlarged in 1917 and again in 1918 to accommodate increased production.

The machine shop, built in 1916, is level with the grade on the west side of the main road. It is north of the leaching plant and south of the power plant. From the machine shop came the fabrication and repair of the standard mechanical equipment necessary for the mining operation.

The power plant generated the lifeblood energy to power the industrial machinery. Electricity and steam heat were produced here and sent to almost every building in the mining camp. Characterized by four towering black smokestacks, the power plant was constructed in three distinct phases.

The general office completes the center industrial zone. Kennecott was formally established in 1906 with the construction of the log portion of the structure. As the mining operation expanded, four additions were completed to the present building. The office was the administrative nucleus for the mining operation. The building contains the company vault and still retains everyday working paper documents from the Kennecott operation.

Four tram lines were built to the Bonanza claim to transport ore from the mines at 6600 feet to the mill at 2200 feet. They were constructed in 1909, 1915, 1916, and 1918.

Surrounding the industrial buildings and covering hundreds of acres of land are the remains of the mill town buildings. To the north of the concentrator are the railroad yard warehouses, oil storage tanks, and cottages for railroad and mill staffs. Several of the smaller cottages have been privately restored to their former condition.

The camp support buildings are south of the concentrator and adjacent to the abandoned railroad grade: the hospital, company stores, dairy, school, cemetery, and large three-story bunkhouses. To the north are found the homes of the Kennecott Company officials in a large residential area along a street called “Silk Stocking Loop.” A tennis court, a bridge across National Creek, and a walkway lay beyond the loop. Bunkhouses, mine shops, and tramway terminals stood at each of the mines.

The all-wood frame Kennecott company town, every building painted red with white trim, remains a complete unit in an inspiring natural setting. There are no non-contributing structures. All were built from 1907 to 1925 and range in condition from excellent to ruinous.

The name Kennecott is derived from a misspelling of the Kennicott Glacier. The mining camp, with its striking red buildings with white trim, dominated by the wood frame 14-story concentrator, is overwhelmed by the Kennicott Glacier and the Wrangell Mountains, which stand 14,000 feet above the camp. The camp is within the Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve.

The Kennecott Mines National Historic Landmark is approximately a 7-8 hours drive from Anchorage. From Anchorage, visitors must drive east on the Glenn Highway (Hwy 1), then south on the Richardson Highway (Hwy 4), then east on the Edgerton Highway (Hwy 10), then continue east on the McCarthy Road, a narrow, gravel road that is 59 miles long.

More Information:

Wrangell-St. Elias National Park & Preserve

PO Box 439

Mile 106.8 Richardson Highway

Copper Center, Alaska 99573

907-822-5234

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2022.

Also See:

Ghost Towns & Mining Camps Across America

Mining on the American Frontier

Sources: