The exact year that the fertile imagination of Oliver Evans first spawned the idea of a land vehicle propelled without the use of horses is unknown. However, as early as 1773, he wrote that “There are witnesses living, to whom I communicated my intentions of applying my improved Steam Engine to propel carriages.”

The Revolutionary War served as only a temporary distraction for Oliver’s growing obsession with creating a steam-powered carriage. On May 19, 1787, he displayed a working model and submitted plans and drawings to the Maryland House of Delegates.

However, even though a patent was approved shortly after, Oliver was not alone in his quest to sever the limitations imposed upon man by Dobbins. Isaac Briggs, John Fitch, James Rumsey, Nathan Read, and John Stevens, to name but a few, were engaged in similar pursuits.

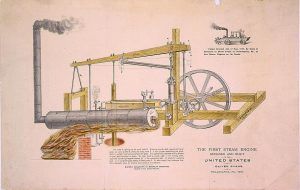

With the establishment of the United States Patent Office, all states were required to relinquish all patents, and inventors were compelled to reapply. Inventor Nathan Read of Warren, Massachusetts, a professor at Harvard and a member of Congress and judge, submitted the first American patent for a self-propelled vehicle.

As an interesting historic footnote, the patent was approved on August 26, 1791. The approving signatures are Thomas Jefferson and George Washington.

Still, it was Evans that stood at the forefront of development and technological breakthrough. By 1792, he had built and tested horizontal and vertical reciprocating engines and developed a revolutionary boiler.

The poison for most visionary minds is rejection, and that was in ample supply when it came to steam-powered vehicles in the closing years of the 18th century. Nathan Read displayed a crude prototype to the Secretary of Defense and Secretary of War, but they vetoed the idea of committing government funds to research and development.

John Fitch of New Jersey, one of the first to successfully utilize steam propulsion for boats, met with similar rejection. In a fit of despondency, he committed suicide shortly after moving to Kentucky.

Meanwhile, Oliver methodically developed his patented steam engine and a wide array of applications for it. However, in his mind, each success was merely a stepping stone on the path to creating a steam-powered land vehicle.

His development of steam-powered grain mills revolutionized that industry. His book, The Young Millwright and Miller’s Guide, was reprinted in 15 editions and a French translation.

On September 26, 1804, he took a major step toward transforming the dream into a reality with the proposition of building steam wagons for the Lancaster Turnpike Company. Simultaneously he was seeking investors, at $30.00 each, to fund the creation of the Experimental Company for the manufacture of steam-powered “road carts.”

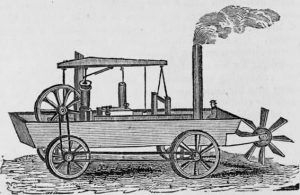

The proposals fell on deaf ears, but Oliver was patient and determined. When commissioned by the city of Philadelphia to build a steam-powered river dredge, he took the liberty of equipping it with wheels to demonstrate the value of having a dredge that could be relocated under its own power, even if the top speed was four miles per hour.

Meanwhile, Colonel John H. Stevens, a hero of the Revolutionary War, turned his attentions toward the development of a steam-propelled vehicle. His first crude model took the streets in 1802.

After extensive experimentation, he determined that regardless of vehicle advancement, road conditions were too primitive to make such vehicles feasible. Interestingly enough, this same viewpoint would dominate the thoughts of early automotive proponents a century later.

Still, Stevens persisted with experimentation and development. In 1826, he built a circular exhibition track in Hoboken, New Jersey, to display his steam-powered vehicles.

In the same year, Samuel Morey, a visionary and prolific inventor, obtained a patent for a new type of engine. Described as a gas and vapor engine, the two-cycle unit utilized a primitive carburetor, electric spark, and water cooling.

By 1830 a veritable explosion in the development of steam-powered “road wagons” and other experimentation led the U.S. Congress to initiate feasibility studies, as well as discuss possible taxation and regulation. A new age was dawning.

In the 1840s, research and development into electric motors added a new wrinkle to the self-propelled vehicle debate that had proponents for the use of steam, compressed air, and various gases. However, it was Moses G. Farmer, in 1847, that first developed an operational prototype using electric motors applied to the wheels.

On his heels came Professor Charles Page, who built a revolutionary vehicle that utilized a 16 horsepower motor driven by 100 Grove cells. To demonstrate its feasibility as well as potential, he would carry twelve people on the streets of Washington D.C at speeds exceeding ten miles per hour.

However, it was Stuart Perry that, with the luxury of hindsight, we now can see as being the most prophetic with his inventions. In 1847 he built a two-cycle engine that used turpentine for fuel, and that was self-started with compressed air.

Still, as the advertisement for the 1903 Jaxon noted, “Steam is easy to harness and is easily understood.” As a result, for most of the 19th-century, steam propulsion dominated thinking and development in regard to self-propelled vehicles.

Ushering in the automobile industry was Sylvester Hayward Roper. His first prototype debuted in 1859, and in the next 20 years, ten vehicles, each more advanced than the last, would roll from his shop. As early as 1863, he developed a two-passenger vehicle with a two-horsepower steam engine and coal-fired boiler suitable for urban usage.

As the velocipede craze exploded in the early 1870s, Roper developed the first motorcycle. One of these was driven to a then astounding speed of one mile in two minutes.

As he chose to be called, W.W. Austen, or Professor Austen, was cut from the cloth of P.T. Barnum. Throughout the country, at fairs and other exhibitions, he attracted tremendous crowds with the pitting of Roper’s cars, and motorcycles, against horses.

As the world stood poised with one foot on the throttle and one in the stirrup, the fascination with the automobile unleashed a torrent of eccentrics and charlatans. Perhaps the most intriguing manifestations of the former were the creations crafted by proponents of spring-powered vehicles, as in spring-powered like a watch.

Further encouraging the experimental fervor were financial incentives. In 1875, the Wisconsin legislature proposed a $10,000 reward to any resident that could produce “a machine propelled by steam or another motive agent as a practical substitute for the use of horses or other animals on highway or farm.”

The stage was now set for Ransom E. Olds, the Duryea brothers, and Elwood Haynes.

©Jim Hinckley, April 2013, updated June 2021.

About the Author: Jim Hinckley is an award-winning author and photographer and an official contributor to Legends Of America through a partnership developed in October 2012. Hinckley is a former Associate Editor of Cars and Parts Magazine and author of multiple books, including several on Route 66. You can follow him on Jim Hinckley’s America.

Also See:

Jim Hinckley – Author & Legends of America Contributor

Legends of the American Automobile