Many different Native American tribes have lived in Iowa over the generations. Each tribe, whether they were residents for centuries, or utilized the land for short periods, had their own culture, language, and traditions.

Ages ago, when Iowa was much different in than it was at the time that European explorers found, a race of human beings not unlike the Eskimos inhabited the territory. The great glacier of the Mississippi Valley was, at that time, receding toward the north. On its edge lived a race of short, stout, flat-featured men and women. Of them, little is known. More has been discovered about those who succeeded the short people — the Mound Builders.

These people were superior in intelligence and civilization to the glacier dwellers. They are called Mound Builders, because all through the Mississippi Valley, and in other portions of the United States, especially east of the Mississippi River, are visible mounds that were built by this ancient people. In Iowa, many can be found in Jackson, Louisa, Clayton and Scott Counties, as well as other areas. The largest and best known are the Effigy Mounds in northeast Iowa.

Situated along the Upper Mississippi River and extending east to Lake Michigan, these mounds were built in the shapes of birds, bear, deer, bison, lynx, turtle, panther or the water spirit; as well as conical mounds for burial purposes. These peoples also built linear or long rectangular mounds that were used for ceremonial purposes that remain a mystery. Some archaeologists believe they were built to mark celestial events or seasonal observances. Others speculate they were constructed as territorial markers or as boundaries between groups.

The animal-shaped mounds remain the symbol of the Effigy Mounds Culture. Along the Mississippi River in northeast Iowa and across the river in southwest Wisconsin, two major animal mound shapes seem to prevail: the bear and the bird. Near Lakes Michigan and Winnebago, water spirit earthworks — historically called turtle and panther mounds — are more common.

The Effigy Mound Culture extends from Dubuque, Iowa, north into southeast Minnesota, across southern Wisconsin from the Mississippi River to Lake Michigan, and along the Wisconsin-Illinois boundary. The counties of Dubuque, Clayton, and Allamakee contain almost all the effigy mounds found in Iowa.

Other mound groups can be found in Iowa, primarily near the banks of the rivers — along the Iowa and the Des Moines Rivers, and bordering other streams that flow into the Mississippi River. Generally, the favorite location was the crest of a hill, or well up toward the top, on terraces. An elevation was chosen, perhaps because of fear of floods or maybe because of security against attack. Some mounds have been found to contain skeletons, stone weapons, pottery and rude engravings on stone. Stone images of the elephant and other animals now foreign to Iowa have been unearthed.

After the Mound Builders had been in possession of the Mississippi and Ohio River Valleys for some time, warlike tribes from both the east and the west pressed upon them. For centuries the great Algonquin family of Indians had occupied the Atlantic Coast. They were encountered by the Norsemen who touched at Cape Cod in the year 1000, and when nearly 500 years later, the English under the explorer, John Cabot, landed, the Algonquin were still there.

At some point, some Algonquin tribes pushed westward, and by way of the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes overflowed the country to the south and into the Mississippi Valley. At the Upper Mississippi River, they met the bold Sioux from the Rocky Mountains.

The Dakota Sioux had crossed the Rocky Mountains and followed the Missouri River and its branches eastward. These western Indians were even more warlike than the Indians of the Atlantic Coast. When the tribes clashed the Mound Builders were crushed. In vain, they tried to oppose the fierce strangers invading the territory and Iowa became a battleground.

The Indians were left in possession of the Upper Mississippi Valley. Iowa was now the field of a long struggle. The Sioux held the region in the north of Iowa and in Minnesota and penetrated into Wisconsin. The Algonquin Indians surged below them to the Missouri River, occupying the rest of Iowa and northern Missouri. The line between the rivals reached about from the mouth of the Upper Iowa River to the mouth of the Big Sioux River.

The two tribes were bitter enemies. Whether the hatred began then or has an origin farther back, is an unanswered question. But, always the Sioux, were known to cruel and bold, and the Sac and Fox, crafty and brave, killing each other on every occasion possible.

It is no wonder that the Indians refused to abandon the land they had invaded. Iowa was an ideal home for them. On the hills and in the valleys were the deer; on the prairies the buffalo. The noble wild turkey dwelt in the woods, and the prairie chicken and ruffed grouse were on every side, in meadows and thickets. The numerous lakes and streams furnished fish, and afforded passage for the bark canoes. The plum and grape were to be had for the picking. The hickory nut and the hazelnut were plentiful, and maize waved in the fields.

The Mississippi River on the east and the Missouri River on the west, with the smaller rivers traversing the interior between, were highways from district to district. The climate, cold in winter, warm in summer, never was monotonous. The blue of the sky and the cleanness of the air were not burdened as now with smoke from cities but were just as nature has intended they should be.

It is easy to understand why the Indians, removed to other places, returned in little bands time and again, to look once more upon the scenes they loved so well. Even the Indians of Michigan and Wisconsin, when brought to Iowa by the government, preferred their new surroundings to the old.

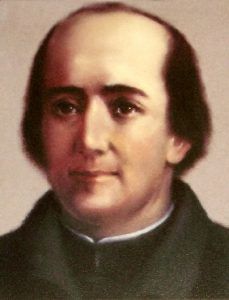

The first Indians seen in what is now Iowa by a white man were of the Illinois tribe. In 1673 Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet, the French explorers, coming down the Mississippi River, landed in southeastern Iowa and encountered Indians, who said they were Illini, or as we term them by the French rendering, Illinois. Illini means “men,” and when these Indians proudly said, “We are Illini,” they meant they were very brave and superior to all other people.

There are also references in records dating about this time to the Mascouten tribe. The name Muscatine evidently is derived from this word. The Mascouten at one time lived on Muscatine Island, and on other territory in that locality. The name is said to signify “place having no woods,” or prairie; some authorities state the true translation is “fire Prairie,” and that great fires used to sweep over the country in Muscatine County.

Long before whites came to Iowa the Mascouten had disappeared, and either were extinct or had united with other tribes. They are said to have been cruel and treacherous, and unfriendly to the Sac and Fox, whom they defeated in a great conflict near the mouth of the Iowa River.

The Illini and Mascouten were Algonquin. But, in the midst of the Algonquin, dwelt for many years a Dakota tribe, the Ioway. The name is spelt in various ways, for example, Ayoua, Ayouway, Ayoa, and Aiouex, but the English style is Iowa or Ioway. The state of Iowa took its name from this tribe. The Ioway were in Southern Iowa when the first explorers penetrated to that section. Their principal village was in the extreme northwest corner of Van Buren County, where the town of Iowaville now stands. Other villages were in Davis and Wapello Counties, and in Mahaska County, which bears the name of an Ioway chief.

The Ioway called themselves Dusty-noses, claiming that they once dwelt on a sandbar, where the wind blew dust into their faces. They were brave and intelligent Indians and were enemies of the other Dakota because an Ioway chief had been treacherously slain on the Iowa River by a band of Sioux.

The Ioway Indians were divided into clans, designated Eagle, Wolf, Bear, Pigeon, Elk, Beaver, Buffalo and Snake, and distinguished one from another by the fashion in which the hair was cut. Pestilence and war reduced this tribe, until, after a massacre by the Sac and Fox in 1823, it ceased to play an important part in the farther history of this region.

The Sac and Fox hold the most prominent place in the story of the Algonquin family in Iowa. The Meskwaki, on their reservation in Tama County, are Fox Indians and are the only tribe with a settlement in the State.

In about 1712 the Sac and the Fox tribes became close allies. Formerly they lived with other Algonquin in Wisconsin and Michigan but together moved to the Mississippi River. In 1805 the Sac had four villages on the Mississippi River — one at the head of the Des Moines Rapids; another about 60 miles above, across the river; another on Rock River back of Moline’s site, and another on the Iowa River.

Fox villages are known to have been at the mouth of Turkey River; where Dubuque now stands; at Rock Rapids, and where Davenport is located. The village on the site of Davenport was one of the oldest Indian towns on the upper Mississippi River.

At the mouth of the Wapsipinicon River, in Clinton County, once was a Sac village, but the largest community of Indians in all this part of the country was at an angle of the Mississippi and Rock Rivers, in Illinois. It was known as Black Hawk’s Town and was called by the Indians Saukenuk. The Fox, as well as the Sac, dwelt there. Its precise location was on the north bank of the Rock River, about a mile from the mouth.

As a rule, the Fox frequented the west side of the Mississippi River and the Sac the east. Finally, all were sent by the government into Iowa.

The word Sac is asserted to be a corruption of Sau-kie or Sau-kee. The Sac pronounced it with a strong guttural accent on the last syllable. One meaning given to the name is “man with the red badge,” it being maintained that the Sac covered his head with red clay when he mourned. Accordingly, the word Mus-qua-kie is held to mean “man with a yellow badge,” because this tribe covered the head with yellow clay. On account of their thieving habits, the Mus-qua-kie were styled by the French as Renards, or Foxes. The Sac and Fox, after they had established themselves along the Mississippi River, proved to be the strongest of the Algonquin in and around Iowa.

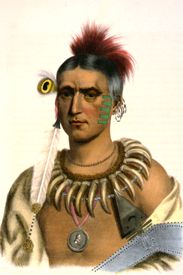

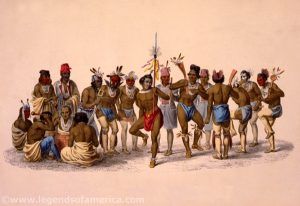

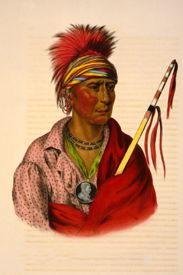

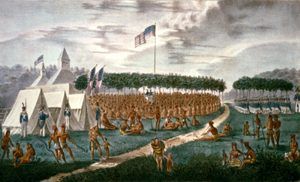

The Sioux Indians were the sole possessors of Iowa north of the Upper Iowa River and in the northwest portion above the latitude of the mouth of the Big Sioux River. They were the Arabs of the Iowa prairies, and their hand seems to have been against everyone who was not a Sioux. The trouble constantly occurring between the Sioux and the Indians south of them compelled the government to interfere. In 1825 a council of all the Indians in Iowa was called at Prairie du Chien. The chiefs gathered, decked in paint and feathers, each tribe striving to outdo the others. The Sioux came on horseback; the Sac and the Fox dashed up the river in their war canoes, singing their songs and boasting.

At the council, the ancient foes glared at one another, but order was kept, and no encounters resulted. A boundary line was fixed, to which the tribes agreed. The Sioux were to hunt north of a line passing from the mouth of the Upper Iowa River through the upper fork of the Des Moines River to the fork of the Big Sioux, and down the Big Sioux River to the Missouri River. The Sac and the Fox were to keep south of this line. They gave permission to the Ioway and the Otoe, both of the Dakota family, to live in this territory, with them.

However, it was soon seen that the Indians were fond of sending war parties across the line, back and forth, hunting scalps instead of deer. Therefore, in 1830, the United States secured, on either side of the line around twenty miles wide, extending from the Mississippi River to the Des Moines River. This strip, 40 miles wide, was termed the Neutral Ground. Indians of any tribe were to hunt and fish here, and no charge of trespassing was to be set against them.

The Great Treaty of Prairie du Chien, by James O. Lewis. On August 19, 1825 a council of all the Indians in Iowa was called at Prairie du Chien to try to reduce inter-tribal warfare within the state. The Treaty of Prairie du Chien was proclaimed the following year.

This answered the purpose of decreasing the encounters between Algonquin, Ioway, and Otoe on one side and the Sioux on the other. Then, in 1841, the government removed onto the Neutral Ground the Winnebago, who had been living in Wisconsin. In Algonquin, the name Winnebago means “turbid water.” The Winnebago were Dakota and claimed to be the people from whom sprang the Ioway, Otoe, and others. They disliked to go onto the Neutral Ground, because on the south were the Sac and Fox, and on the north were the Sioux, and thus they were between two fires.

However, they grew to love the Iowa reservation. After they were taken to Minnesota in 1846 they persisted in coming back, until civilization shut them out forever. In Iowa, the Winnebago hunting grounds were along the Upper Iowa River, Turkey, Cedar, and Wapsipinicon Rivers.

Potawatomi, with some Chippewa and Ottawa, all Algonquin, were removed from Michigan to the southwestern part of Iowa. The name Potawatomi signifies “makers of fire,” denoting a free and independent people who had their own council fires. The agency for the Potawatomi was in Mills County, at Trader’s Point. A village stood on the bank of the Nishnabotany River. It was called Miau-mise and was not far from Lewis in Cass County. Here also was a burying ground.

In 1846 the Potawatomi and the other tribes mingling with them were sent farther west, but, like the Winnebago, they returned to Iowa time after time.

Long ago the Sioux had a large summer camp near where Dubuque is. They called themselves Dakota, meaning a “united band.” Their favorite haunts in Iowa were the headwaters of the Des Moines and Iowa Rivers, and around the northern lakes. They placed their dead in trees or on scaffolds. The Algonquin buried theirs.

For years afterward, the ancient graves of these many Indian tribes could be seen up and down the Mississippi River.

Iowa Tribes:

Dakota Sioux – After the Iowa Indians moved from the northern part of the present State of Iowa, the Dakota occupied much of the territory they had abandoned until the Sac and Fox settled in their neighborhood shortly before and immediately after the Black Hawk War of 1832 and harassed them so constantly that they withdrew.

Fox – This tribe began moving into Iowa sometime after 1804 and by the end of the Black Hawk War all were gathered there. In 1842 they parted with their Iowa lands and most of them removed to Kansas with the Sac, but, shortly after the middle of the 19th century some began to return to the State and by 1859 nearly all had come back. They bought a tract of land near Tama City to which they added to from time to time and where they have lived ever since.

Illinois/Illini – Jean Baptiste Louis Franquelin, a French mapmaker, located the Illinois on the upper Iowa River in 1688; but, Father Jacques Marquette, on his descent of the Mississippi River in 1673, found the tribe and the Moingwena near the mouth of the Des Moines River. When he returned he found that they had moved to the neighborhood of Peoria, Illinois. The name Des Moines is derived from that of the Moingwena.

Ioway – Iowa, or Ayuwha, was a term borrowed by the French from the Dakota that signifies “Sleepy-ones.” The Iowa people are of Sioux stock and closely related to the Otoe and Missouri tribes. They moved about a great deal, mostly in the states of Iowa and Minnesota. Through various treaties with the U.S. Government, they lost their lands in Minnesota, Iowa, and Missouri. The Ioway practiced farming and lived in villages; however, bands that lived farther west adopted more of the customs of the Plains Indians. In 1836, another treaty assigned part of them a reservation along the Great Nemaha River in present-day Brown County, Kansas and Richardson County, Nebraska.

Missouri – This tribe is said to have had the same origin as the Ioway and to have moved with them and the Otoe to the Iowa River, where the Ioway remained while the others continued on to the Missouri River.

Omaha – While the Omaha tribe usually lived west of the Missouri River, they wandered for a time in western Iowa before moving over into Nebraska.

Otoe – The Otoe were once part of the Siouan tribes of the Great Lakes region, commonly known as the Winnebago. At some point; however, they began to migrate southwest where they were located just north of the Missouri River and west of the Mississippi River in what is now northern Missouri and Iowa.

Ottawa – Representatives of this tribe were a party to a treaty made in 1846, ceding Iowa lands to the United States.

Ponca – The Ponca accompanied the Omaha while they were in western Iowa.

Potawatomi – The Prairie Potawatomi settled in western Iowa before removing to Kansas. They ceded their lands in 1846.

Sac – The Sac moved into Iowa and then to Kansas in 1842.

Winnebago – In 1840 this tribe went to the Neutral Ground in Iowa that was assigned to them by a treaty of September 15, 1832. Later, in 1848, they removed to Minnesota.

Frederick Webb Hodge, 1910. Compiled with additional edits by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated October 2019.

Also See:

Historic Rivertowns of McGregor and Marquette

Sources:

Effigy Mounds, National Park Service

Hodge, Frederick Webb; Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico; Smithsonian Institution; 1910

Sabin, Henry and Savin, Edwin L.; The Making of Iowa; A. Flanagan Co.; Chicago, New York, 1900