“I will promote mining interests to the best of my ability because their prosperity is the prosperity of the nation.” — President Abraham Lincoln, 1865

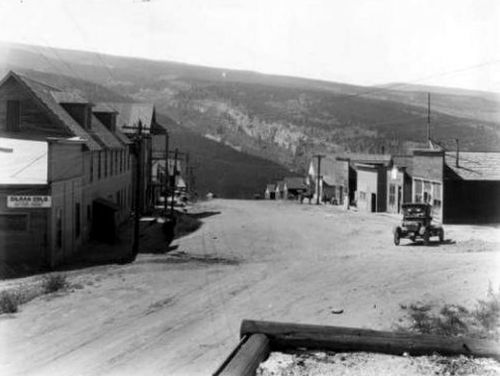

Sitting on the side of Battle Mountain about 12 miles southeast of Avon, Colorado, is the old company town of Gilman. The now-abandoned town was initially founded in 1886 by miners searching for silver but later became a center of lead and zinc mining.

By 1876 several lodes silver-lead deposits had been found in the area, setting off the Colorado Silver Boom. The rush began in nearby Leadville as thousands flocked to the town to dig for their fortunes. Soon, the miners spread out, with many filtering down Tennessee Pass, traveling over old Ute Indian trails. As more adventurers swarmed to the area, the trail widened to allow mules or oxen teams. However, the route remained treacherous and was aptly named “Battle” for a reason.

By 1879, ore strikes were made in what would become the Battle Mountain District, the first in Red Cliff. The same year, Kelly’s Toll Road opened, generally following the same path as present-day Highway 24. It started in Leadville and continued over Tennessee Pass and down Battle Mountain to the Eagle River Valley. Numerous miners then spread deeper throughout the canyon and onto the steep slopes of Battle Mountain.

Judge D.D. Belden discovered what would become the Belden Mine in May 1879. Later that year, Joseph Burnell, a Leadville newspaperman, discovered what would be developed into the Iron Mask Mine. Other mines would soon be discovered, including the Black Iron, Ida May, Little Duke, Ground Hog, May Queen, Kingfisher, Little Chief, Crown Point, and Little Ollie, the oldest dating back to 1878.

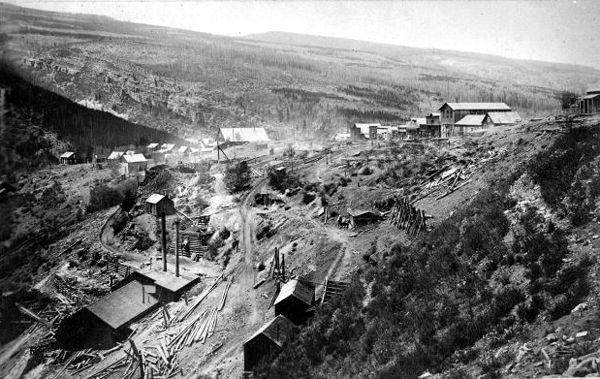

Here, several mining camps sprouted up called Belden, Rock Creek, Bells Camp, Cleveland, and Clinton (later called Gilman). By 1880, Battle Mountain had a smelter, a stamp mill, a sawmill, and a mining district with elected officers to settle disputes about the scores of scattered mining claims.

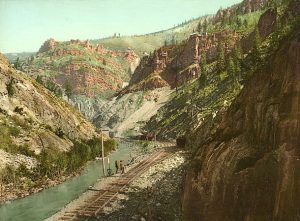

The Denver and Rio Grande Railway reached Redcliff in November 1881 and by the next year extended through Eagle River Canyon with a station at Belden at the base of Battle Mountain. By this time, Redcliff had become Battle Mountain’s first boomtown, with two saloons, several hotels, an opera house, and several other businesses.

During this time, one of the many area miners was a man named John Clinton, who was also a judge and speculator from Red Cliff. In the early 1880s, he acquired several mining operations in the vicinity, including the profitable Iron Mask Mine, which would become the principal producer of lead and zinc within Colorado for decades.

Near the Iron, Mask Mine was a growing population of log cabins and tents along the steep mountainside. Clinton soon improved the mining operations and established a mining camp on a 600-foot cliff above the Eagle River on a flank of Battle Mountain. Sitting at an elevation of 8950-feet, the camp was named for him. The first building in Clinton was a saloon built in 1884.

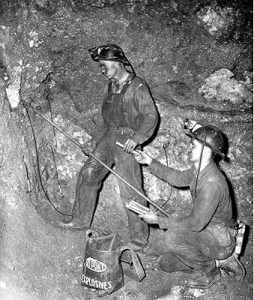

In 1886, the Iron Mask Mine constructed the first tramway on the slope of Battle Mountain to connect the mine with the railroad at the bottom of Eagle Canyon. Afterward, the mine began shipping over 100 tons of ore per day. The same year, the Colorado state inspector of mines estimated that the Iron Mask contained 100,000 tons of ore worth $3,482,000, and the mine’s workforce of fewer than 80 employees doubled in two weeks.

With the increase in mine production and the bright prospects for the future, the Clinton mining camp quickly transformed into Battle Mountain’s second boomtown. In 1886, it received its first post office and was renamed Gilman to avoid confusion with Clinton, California. It was named for Henry Gilman, the well-liked superintendent of the Iron Mask Mine. Henry Gilman had also donated land for a schoolhouse and served as president of the first school board.

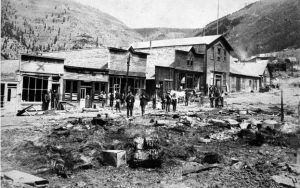

By late 1887, the fledgling town boasted a hotel, a boarding house, a general store, a billiard hall, a sampling room, a newspaper called the Gilman Enterprise, several saloons, and a population upwards of 1,000 people. Like many other mining camps, it also hosted several rowdies who might ride their horses into a saloon, shoot out the lights, and conduct acts of banditry and violence.

By 1890 the initial rush was over, and the population of Gilman dropped to 442. The silver crash of 1893 caused an immediate cessation of many of the mines, and the Battle Mountain mines decreased production. The operations at Gilman would not resume fully for twenty years.

In 1899, Gilman was almost destroyed by a fire that took down the Iron Mask Hotel, the school, the shaft house of the Little Bell Mine, and much of the business district.

By 1900, some $8 million in silver, gold, and lead ore had been recovered on Battle Mountain. However, by this time, the area mines were no longer producing much silver and turned to mining zinc.

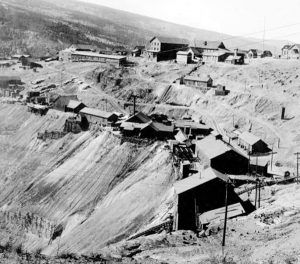

In 1905, The Eagle Milling and Mining Company reopened the Iron Mask Mine with a new emphasis on zinc production and installed a roaster and magnetic separator that separated the zinc minerals. In 1912, the New Jersey Zinc Company began buying up the claims and land on Battle Mountain, including the town of Gilman, and the days of independent miners came to an end.

The Iron Mask Mine was renamed “Eagle 1” and “Eagle 2” by 1919. The mining operations transitioned increasingly to zinc, although the Eagle Mine was still the leading producer of silver in the state in 1930. Eventually, the mine boasted 62 miles of tunnels beneath the mountain.

Efficiency was an essential part of Gilman’s longstanding commercial success as a company town. The company began buying and tearing down all the old cabins and, by 1919, erected dozens of uniform houses placed in rows down the hill from the shaft house. With black tar paper roofs and gray paint, these utilitarian houses were well insulated and had electricity and hot water. One early resident, Vesta Coursen, would later write:

“We had to come out to the wilds of Colorado to find modern improvements such as we had not enjoyed in the civilized East!”

The company maintained total ownership of Gilman, including the housing, school building, post office property, and all of the town’s retail space. The company built a two-story clubhouse with a pool hall, basketball court, and library-lounge, that served as the hub for recreation. They also built a hospital, a general store, a dormitory, and a mess hall to accommodate 60 men.

The clubhouse often brought the whole community together for monthly dances, sing-a-longs, Hollywood movies, and holiday celebrations. Further entertainment was found during the winter when residents enjoyed sledding down the steep hillsides on cardboard, garbage can lids, coal shovels, and toboggans, sometimes to the base of Battle Mountain. Skiing was introduced to the community by Scandinavian workers in the 1920s, long before the nearby ski resorts were founded. In these early days, the skiers utilized plain wooden skis without fancy boots or bindings and made poles with broomsticks rammed through coffee can lids. The residents also enjoyed the unspoiled wilderness around Gilman for hunting, fishing, hiking, and camping.

The company not only owned Gilman’s properties, but it also organized many aspects of life for its residents. It controlled the school board by appointing members from its own ranks, screened Hollywood movies before they were shown in the clubhouse, and provided high-quality healthcare for all employees and families.

Due to the precarious route over Battle Mountain to reach Gilman and Red Cliff from Leadville or Minturn, a new road over Battle Mountain was completed in January 1923. Following the old Kelly’s Toll Road, the job took two years and required the removal of 75,000 cubic yards of rock. It wasn’t until the winter of 1929-30 that the road was able to stay open. This route became Highway 24, and in 1929, it became open year-round, reducing the self-contained entertainment in Gilman. But, more significant factors would affect the town at about this time.

Zinc remained the economic mainstay until 1931, when low zinc prices forced the company to switch to mining copper and silver ores. Amid the Great Depression, most industrial mining virtually ceased in Colorado, but unlike similar mechanized mines, the Eagle Mine never closed. Though the company did lay off many single employees and cut the hours and wages of remaining workers, comparatively speaking, the Eagle Mine was quite successful during this time, producing 85 percent of Colorado’s copper and 65 percent of its silver. In 1933, the company recalled many of Gilman’s laid-off workers.

By 1936, Gilman had 85 company houses. This same year, yet another new road was built over Battle Mountain, and in 1940, the Red Cliff Bridge was completed just east of Gilman, one of only two steel arch bridges within the entire state. Today, the bridge is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Zinc production resumed in 1941 and remained the principal product of the Gilman mines. At this time, the town employed as many as 375 people, and during World War II, miners were exempt from the military draft because the zinc they mined was vital to the country’s war effort.

After World War II ended, Gilman’s clubhouse was enlarged and updated with a new dance floor, a modern kitchen, and a bowling alley – the only one in Eagle County.

In 1950, the Gilman mines were profitable, and the town and its residents were stable, safe, and happy. However, for decades other hard rock and coal mining companies in Colorado and across the nation had earned a reputation for exploiting their employees, resulting in unionization and strikes. From 1915 to 1950, Gilman miners didn’t feel the need to unionize due to the company not having cut hours and wages during the Great Depression, the town’s longstanding social stability, and the company’s commitment to health and safety.

However, the Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers began to organize in Gilman and convinced most employees that the union meant better wages, health insurance, and improved working conditions. As a result, the Gilman workers approved the union organization, which caused strife between the workers and the mining company and discontent between the miners themselves.

In the meantime, in 1951 alone, the company extracted some $12,000,000 in ore, and the mining district became the richest and most successful in Eagle County. Although zinc was the main product, enough gold was still recovered to cover the mining expenses.

Demands for a new contract that included a ten-cent-an-hour raise and a separate health clinic with its union doctor resulted in a brief strike in August 1854, which suffered internal conflict between the miners from the start. As many mill and surface workers did not want anything to do with the union or the strike, fights erupted within the first few days. In the end, the company agreed to a five-cent-an-hour raise, and the mine was running at total capacity again before the first snowfall.

But the idyllic community of Gilman would never be the same. Formerly friendly co-workers no longer talked to each other, tensions mounted between retail establishments that once provided a reliable credit system with the miners, cracked down and demanded immediate payment, and weakened corporate paternalism.

In 1959, Gilman workers struck again over pay rates, arbitration, and management rights. The dispute was settled the following year, which stabilized Gilman’s labor situation, but tensions remained. However, the U.S. military’s demand for zinc remained strong, and in the 1960s, the town supported a few hundred people and boasted an infirmary, grocery store, and bowling alley.

In 1965, the fate of Gilman was in limbo as the company faced not only stagnant zinc prices but the need for capital improvements and expansion. That same year New Jersey Zinc sold out to Gulf and Western Industries, Inc., a growing auto parts corporation that wished to utilize the zinc in the use of chrome.

By 1970, total production at the mines was 10 million tons of ore, including zinc, gold, silver, and copper.

However, by the mid-1970s, most auto manufacturers had abandoned chrome in their vehicles, and the mine’s zinc reserves were nearly exhausted. A spike in gold and silver prices kept a much smaller operation going for a few years, but ultimately the Eagle Mine closed at the end of 1977. In December 1977, the operation laid off 154 miners after a two-week notice, with 16 remaining on the payroll. Afterward, some limited copper and silver production occurred, but that too soon ceased, and the pumps were deactivated, and the mine was allowed to flood.

In 1983, the town and its mines were sold to a Canon City businessman named Glen Miller, who planned to put the land to multiple uses, including converting mine tailings into fertilizer, creating new residential development, and the possibility of developing a ski resort. However, within a year, he sold the town to the Battle Mountain Corporation.

Gilman became an official ghost town in the spring of 1985 when the Battle Mountain Corporation evicted its remaining residents, and the post office closed its doors forever.

After the closure of the mine and the abandonment of the town, a 235-acre area, which included eight million tons of mine waste, was designated a Superfund site by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Massive amounts of pollutants had been released into the ecosystem, which placed the site on the National Priorities List.

CBS Operations, Inc., who bought Viacom International, Inc., which owned the controlling shares of New Jersey Zinc Company, was deemed responsible for the site’s cleanup. Cleanup of the mine began in 1988 with the relocation of mine wastes and capping of the main tailings pile. According to the EPA, the network of mines included “an estimated 70 miles of underground mine tunnels”. Today, the cleanup has been declared a success.

In 2004, the property was purchased by Florida real-estate developer Edward R. Ginn for $32.75 million with plans to develop a gated community, a 10-lift private ski resort, golf course, a luxury hotel, and parcels for hundreds of private homes. The development proposal required an annexation into Minturn for the town’s services, which residents approved in 2008. However, Ginn filed for bankruptcy the next year. The property then became part of the Battle Mountain Development Company who planned a massively scaled-back version of the project. There are still plans today to subdivide the land for re-development, but nothing has been done as of this writing.

Gilman still sits silently on a shoulder of Battle Mountain overlooking the valley below. Its large shaft house and many buildings sit empty and deteriorating. From Highway 24, overlooking the old company town, visitors can see graffiti, crumbling walls, cracked chimneys, and broken windows in the town’s many buildings. The old unused railroad track that once hauled ore from the Eagle and Belden mines can be seen in the canyon below. Today, it is choked with weeds and littered with small boulders that have tumbled onto the rusting tracks. An old station wagon sits rusting along the steep mountainside.

The old pipeline/trestle system that once pushed the tailings to a location downstream still mostly stands rusting and broken in large sections. When the mine closed, the EPA used the trestle system to deliver contaminated water from the Eagle Mine to a water treatment plant.

“No Trespassing” signs hang on the closed gates, and more signs are posted warning trespassers of “Hidden and Visible Dangers” and the “Risk of Injury or Death.” However, in years past, many have ventured onto the property, despite the warnings. This is evidenced by the amount of graffiti on the buildings and photographs taken by trespassers. Inside the buildings, x-rays are strewn about the old hospital; mine records remain in the offices, furniture and appliances sit rusting and deteriorating in the houses, and a rusty swing set and a slide still sit in the old schoolyard. Mine buildings are filled with old equipment and abandoned vehicles.

Unfortunately, some of these trespassers were doing much more than taking photographs – they were vandalizing the properties of both Gilman and Belden in the canyon below. The Eagle County Sheriff’s Department stepped in and now cites trespassers with a ticket and a fine. To help with the enforcement of the no-trespassing laws, the local Crime Stoppers organization rewards tipsters with as much as a $1,000 reward.

Gilman is located southeast of Minturn and north of Tennessee Pass along U.S. Highway 24. The remnants of the townsite are visible in many places along the curves of the highway.

©Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, November 2021.

“There are no wastelands in our landscape quite like those we’ve created ourselves.”

— Tim Winton

Also See:

Gilman-Red Cliff Photo Gallery

Colorado Ghost Towns & Mining Camps

Colorado – The Centennial State

Sources:

Mining History Association

Places That Were

Substreet

Vail Valley Magazine

Wikipedia