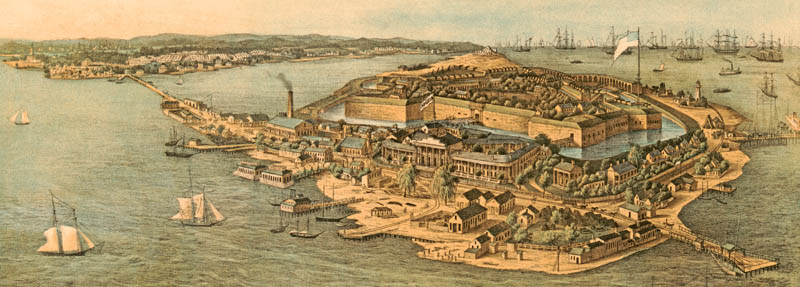

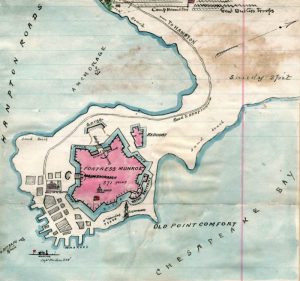

Fort Monroe is a military installation overlooking the Chesapeake Bay in Hampton Roads, Virginia. The largest stone fort ever built in the United States, it is also the only moat-encircled fort remaining on active duty.

Over 400 years ago, in 1607, English explorer Captain John Smith, who later founded Jamestown, came ashore near here and surveyed the area in 1608. Pronouncing the area a “little isle fit for a castle,” settlers began to make their homes here at the mouth of Hampton Roads at Point Comfort. In the fall of 1609, Captain John Ratcliffe and the colonial settlers built a wooden structure large enough to hold 50 men and seven mounted cannons and called it Fort Algernourne. It was the first English fort in Virginia.

We “rowed over to a point of land where we found a channel and sounded six, eight, ten, or twelve fathoms, which put us in good comfort. Therefore we named that point of land Cape Comfort.” George Percy, English colonist, April 1607

For the next four centuries, this point served as the key defensive site at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay.

In September 1609, Captain John Smith returned to England, and Captain James Davis assumed command of the newly built fort in October.

The fort was very close to the Kecoughtan village, and in one of the acts leading to the first Powhatan War, the village was attacked and captured by the English on July 9, 1610, who built another fort called Fort Charles. Another small fort called Fort Henry was also built to protect the Kecoughtan settlement.

In mid-1611, a fire accidentally destroyed Fort Algernourne, but Davis quickly rebuilt it.

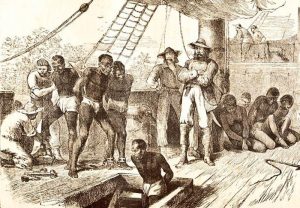

The first Africans brought to the North American colonies arrived on a Dutch ship at Old Point Comfort in 1619. Colonist John Rolfe noted in his diary that in August 1619, more than 20 Africans arrived at Point Comfort on the ship White Lion. These Africans were traded for food and supplies, which marked the beginning of slavery in the colony.

Fort Algernourne fell into disuse after 1622. Another fort, known only as “the fort at Old Point Comfort,” was constructed in 1632 and discontinued after 1667.

Fort George was built on the site in 1728. A hurricane destroyed its masonry walls in 1749, but a reduced force used the wooden buildings in the fort from about 1755 until at least 1775.

During the American Revolution, as Patriot and French forces approached Yorktown in 1781, the British established batteries on the ruins of Fort George. Shortly afterward, during the Siege of Yorktown, the French West Indian fleet occupied these batteries. Throughout the Colonial period, fortifications were occasionally manned at the location.

With the destruction of Fort George, Old Point Comfort was once again unfortified, and the entire Chesapeake Bay was vulnerable to attack.

In the late 1700s, before the Point Comfort lighthouse was built, a soldier was stationed there to keep a lantern burning at night to warn passing ships of the small but treacherous point of land.

The Point Comfort lighthouse was built in 1802 and has been a beacon ever since. The octagonal stone tower stands 54 feet tall and is still an active aid to navigation maintained by the United States Coast Guard. The lens’s glass prism magnifies the light, making it visible for 18 miles. Two lighthouse keepers and their families shared the house next door to the lighthouse, built in 1875 until the light was automated in 1973. It is the oldest operating lighthouse on the Chesapeake Bay.

During the War of 1812, the British Navy fleet sailed into the Chesapeake Bay unchallenged. After their futile attempt to seize the town of Norfolk, British forces under Rear-Admiral Sir George Cockburn landed at Old Point Comfort and used the lighthouse tower as an observation post. From there, they invaded and captured Hampton on June 25, 1813. Afterward, they routed an American force at Bladensburg before capturing and burning Washington, D.C., and unsuccessfully attacking Baltimore, Maryland.

In 1819, the construction of Fort Monroe began as part of a coastal defense strategy developed by the U.S. Army following the War of 1812. President James Madison put Brigadier General Simon Bernard, a French-born military engineer, in charge of designing and overseeing the fort’s construction. Bernard, formerly a French brigadier general of engineers and aide to Napoleon, had been banished from France after Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815. He then moved to the United States and was commissioned as a brigadier general in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Fort Monroe was the first of the third system forts to begin construction and was intended to be a headquarters for the system and a fort. The massive stone and brick-walled fort was built in an irregular hexagon shape with seven bastions. The initial design provided for up to 380 guns and was later expanded to 412 guns, intended for a garrison of 600 troops in peacetime and up to 2,625 troops in wartime.

Named for James Monroe, the fifth president of the United States, it was first garrisoned in June 1823 by Battery G of the 3rd U.S. Artillery Regiment, though construction continued for years. The construction began by utilizing slave labor, which military convicts gradually replaced. The granite for the walls came from rock quarries in Virginia and Maryland, while local contractors supplied the other building materials. Upon its completion in 1834, Fort Monroe cost nearly two million dollars and covered 63 acres of land, with its walls stretching 1.3 miles. Depending on the tide, the water fed through a gate from Mill Creek ranges from three to five feet deep. By the time construction was finished, only the Point Comfort Light House existed beyond the moat.

“Quarters One” was constructed in 1819 as a residence and headquarters for Fort Monroe’s commanding officer. It is one of the oldest buildings on the post and the oldest house inside the moat. It was the headquarters of Fort Monroe for many years, and from 1819 to 1907, it served as the Fort Monroe commander’s quarters. It was located at 151 Bernard Road and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2011.

Before the Civil War, the fort became a prime training and assembly point for artillerymen, including future Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and Joseph E. Johnston. As a young lieutenant, Lee was stationed at Fort Monroe from 1831 to 1834 and directed the final phase of construction and oversaw construction at future Fort Wool for a time. Just 24 years old at the time, he married, and his first child, George Washington Custis Lee, was born at the fort in September 1832. His quarters, built in 1823, remain occupied by military personnel and their family today.

The Army briefly detained the Native American Chief Black Hawk at Fort Monroe following the 1832 Black Hawk War.

When construction was completed in 1834, Fort Monroe was called the “Gibraltar of Chesapeake Bay.” Its impressive artillery included a 42-pounder cannon with a range of over one mile. In conjunction with Fort Calhoun (later Fort Wool), this was just enough range to cover the main shipping channel into the area.

From 1824 to 1946, Fort Monroe was the site of a series of artillery schools. The first was the Artillery School of Practice, which was closed in 1834 but was revived in 1858–61. Fort Monroe also hosted the Old Point Comfort Proving Ground for testing artillery and ammunition from the 1830s to 1861. After the Civil War began, this function relocated to the Sandy Hook Proving Ground in New Jersey.

The Chapel of the Centurion was consecrated in May 1858. It is named for the Centurion Cornelius, the first Roman soldier and gentile who converted to Christianity. It is one of the country’s oldest wooden churches on an army base.

During the Civil War, Fort Monroe played an important role. After South Carolina opened fire on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor on April 12, 1861, the war began. Five days later, Virginia’s legislature passed the Ordinance of Secession of Virginia to withdraw from the Union and join the newly formed Confederate States of America. However, President Abraham Lincoln was determined to keep Fort Monroe in the Union. On May 7, President Lincoln landed at Old Point Comfort and was escorted to Quarters No. 1. After inspecting the burnt-out town of Hampton, he sent troops to move south to capture Norfolk on May 9, and the town was surrendered the next day. The president also reinforced Fort Monroe so it would not fall to Confederate forces. Union forces held it throughout the Civil War, and several sea and land expeditions were launched from there. The fort was also headquartered in the Union Department of Virginia and North Carolina. By the end of May 1861, nearly 4,500 officers and men under the command of Major General Benjamin F. Butler were assigned to its defense.

On April 20, the Union Navy burned and evacuated the Gosport Navy Yard in Portsmouth, destroying nine ships in the process, keeping Fort Monroe as the last bastion of the United States in Tidewater, Virginia. The Confederacy’s occupation of Norfolk gave it a major shipyard and thousands of heavy guns, but they held it for only one year. Confederate Brigadier General Walter Gwynn, who commanded the Confederate defenses around Norfolk, erected batteries at Sewell’s Point to protect Norfolk and control Hampton Roads.

The Union dispatched a fleet to Hampton Roads to enforce the blockade. On May 18–19, 1861, Federal gunboats based at Fort Monroe exchanged fire with the Confederate batteries at Sewell’s Point. The little-known Battle of Sewell’s Point resulted in minor damage to both sides. Several land operations against Confederate forces were mounted from the fort, notably the Battle of Big Bethel in June 1861.

A few weeks later, on May 23, 1861, voters of Virginia ratified the state’s secession from the Union.

On the same day, another significant event occurred when three slaves belonging to Confederate Colonel Charles Mallory of Hampton escaped to Fort Monroe. The following day, Fort Monroe’s commander, Major General Benjamin Butler, met with them at Quarters One and learned that they would be used to build Confederate fortifications. Mallory’s emissary, Major John B. Cary, demanded that the runaways be returned per the Fugitive Slave Act. However, on May 27, Butler met with Major Cary and asserted that because Virginia now claimed to be a foreign country, this law no longer applied, and the three slaves were considered “contraband of war” and would not be returned. His decision is referred to “Fort Monroe Doctrine.”

Within no time, the news spread, and Fort Monroe quickly earned the nickname “Freedom Fort.” Hundreds of African-American families streamed into the area around Fort Monroe. In the following years, hundreds grew to thousands, and just four years later, more than 10,000 newly emancipated African Americans lived in the area surrounding Fort Monroe. Across Mill Creek, adjacent to Camp Hamilton in an area that would become Phoebus, a contraband “Slabtown” was established, and in the ruins of downtown Hampton, the Grand Contraband Camp rose from the ashes.

On August 6, 1861, Congress formally approved Butler’s action with “An Act to Confiscate Property Used for Insurrectionary Purposes.” It was the first step in enlisting thousands of black men in the Union forces and issuing President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

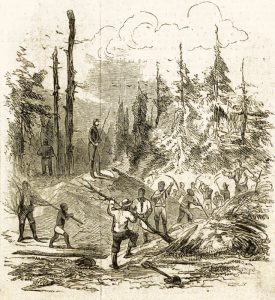

In March 1862, Congress passed a law formalizing this policy. The Union Army initially employed many contrabands in support roles, such as cooks, wagon drivers, and laborers. Beginning in January 1863, the United States Colored Troops were formed, and many contrabands were enlisted. These units were composed primarily of white officers and African-American enlisted men, which eventually numbered nearly 180,000 soldiers.

On March 9, 1862, the naval Battle of Hampton Roads took place off Sewell’s Point between two early ironclad warships, CSS Virginia (aka Merrimac) and USS Monitor. These two Ironclads sat low in the water – barely breaking the surface as they steamed along. For the first time, two opposing warships were outfitted in iron armor. The iron would prevent damage due to cannon and gunfire and would, seemingly, protect the crew. Previous vessels had been made solely of wood. In this water, they faced each other in a dramatic battle that drew observers from both fronts, including President Abraham Lincoln himself. While the outcome was inconclusive, the battle marked a change in naval warfare and the end of wooden fighting ships.

Later that spring, the continuing presence of the Union Navy based at Fort Monroe enabled federal water transports from Washington, D.C., to land unmolested to support Major General George B. McClellan’s ill-fated Peninsula Campaign. Formed at Fort Monroe, McClellan’s troops moved up the Virginia Peninsula during the spring of 1862, reaching within a few miles of the gates of Richmond about 80 miles to the west by June 1. For the next 30 days, they laid siege to Richmond. Then, during the Seven Days Battles, McClellan fell back to the James River below Richmond, ending the campaign. Fortunately for McClellan, during this time, Union troops regained control of Norfolk, Hampton Roads, and the James River below Drewry’s Bluff (a strategic point about 8 miles south of Richmond).

In 1864, the new Union general-in-chief, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, devised his series of spring offensive operations against the Confederacy. Major General Benjamin Butler commanded the newly formed Army of the James, headquartered at Fort Monroe. The two corps under his command, including some 25 regiments of United States Colored Troops, were assigned to push against Richmond and Petersburg. His presence south of Richmond forced General Robert E. Lee to dispatch troops from the Army of Northern Virginia to meet the threat.

Following the Civil War, Confederate President Jefferson Davis was accused of treason, plotting the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, and mistreatment of Union prisoners of war. In May 1865, he was escorted to a casemate cell within the walls of Fort Monroe, chained in ankle irons for three days, and monitored by soldiers who ensured that he ate, made no escape attempt, and did not commit suicide.

However, newspaper accounts aroused sympathy for him, even in the North, and Union Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton soon ordered the irons removed. Davis was moved to spacious quarters in the officers’ hall and was allowed visitors and exercise. In May 1866, his wife, Varina Howell Davis, took up permanent residence at Fort Monroe. After two years, he was transferred to civilian custody on May 13, 1867. Soon afterward, he was released on $100,000 bail put up by the likes of Horace Greeley, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and even Gerrit Smith, a former radical abolitionist. Davis was never brought to trial. His cell in the casemated fort walls is now part of its Casemate Museum.

The casemates, or vaulted chambers inside the fort’s walls, consist of a series of arches above, below, and in the walls that connected the chambers, giving the structure formidable strength. Casemates allowed soldiers to fire cannons from relative safety. Over the years, the casemates in these 10-foot-thick walls were used for defense, living quarters, a prison, an officers’ club, and a museum.

The Artillery School of the U.S. Army was established at Fort Monroe in 1867 and lasted until 1907 when it was redesignated as the Coast Artillery School.

The Board of Fortifications, chaired by Secretary of War William C. Endicott, met in 1885 to consider the future of U.S. coast defenses. In 1886, the board’s report recommended an across-the-board improvement program, often called the Endicott program. This included replacing all weapons with modern breech-loading guns and mortars in reinforced concrete batteries with earth cover and providing controlled minefields in ship channels. Fort Monroe was to be one of the largest installations of this program, and in 1896, construction began on new gun batteries there. The fort was the headquarters of Harbor Defenses of Chesapeake Bay.

Fort Monroe, Virginia Battery, Kathy Alexander.

Over many years, several important hotels were built in Fort Monroe. The first was the Hygeia Hotel in 1822, built before Fort Monroe was completed. Named after the Greek goddess of health, it initially provided housing for the workers constructing Fort Monroe. Engineers and officers also stayed there until housing was available on the new base. The hotel, built in a Greek Revival style, expanded to over 200 rooms and soon became a tourist destination. Dignitaries, including Congressman Henry Clay, President Andrew Jackson, President John Tyler, and Edgar Allan Poe, also visited the hotel. It was demolished in 1862 to clear an area for the fort’s defense.

In 1868, Henry Clark began work on the second Hygeia Hotel. However, it was not successful until 1876, when Harrison Phoebus, a prominent local businessman, began to manage the Hygeia and made it one of the best-known hotels in North America. The four-story structure included elevators, electricity, a 9,000-square-foot dining room, and therapeutic baths. The southern resort complex, including support structures, extended 700 yards along the waterfront and could accommodate 1,000 guests.

In 1902, after the Spanish-American War, the Federal government planned an expansion of Fort Monroe and revoked permission for the second Hygeia Hotel to use the land. Unfortunately, what may have been the most expensive building complex in America was torn down. Making matters worse, the expansion plans were never implemented, and the site of the old hotel became waterfront parkland.

The Sherwood Inn was a cottage built by post-sutler Dr. Robert Archer in 1843. After the Civil War, Mrs. S.F. Eaton acquired the property in 1867 and operated it as a boardinghouse for 20 years, gradually enlarging the inn to accommodate 175 guests. Local businessman H.M. Booker then purchased the establishment and substantially renovated it after a fire damaged the three upper floors in December 1896. Booker sold the Sherwood Inn to the federal government during World War I for use as an officers’ mess and quarters. When World War I ended, the Inn reverted to a hotel for civilian guests, though it continued to provide meals for officers. In 1932, Randolph Hall opened as bachelor officers’ quarters, and the Sherwood Inn was condemned and demolished.

The wood-frame Chamberlin Hotel was built in 1896 and catered to tourists and officers at Fort Monroe. Named for the famed restaurateur and original owner John Chamberlin, the luxurious six-story resort hotel immediately became a major competition to the waterfront Hygeia Hotel. The hotel provided its customers with golf, tennis, riding, high-end cuisine, and curing services such as Electric, Nauheim, and Radio Baths.

“No European’ cure’ surpasses and few compare with this luxurious American Resort Hotel — so wonderfully situated in the midst of a happy combination of land and sea diversions and accessible from every point in the United States. — Chamberlin Advertisement, 1916

Though the U.S. Army required the removal of the Hygeia Hotel in 1902, it allowed The Chamberlin to continue at Old Point Comfort.

Unfortunately, just before dinner on Sunday, March 7, 1920, flames erupted in the hotel and spread so quickly that it was “a roaring inferno when firefighters arrived.” The 400 guests at the posh Old Point Comfort resort were all able to escape with hundreds of employees. Some 20,000 spectators watched as the flames raged all night, leaving the landmark in smoldering ruins. Caused by faulty wiring, the blaze also destroyed two nearby stores and two Fort Monroe military classroom buildings.

Government Dock and Hotel Chamberlin at Old Point Comfort, Virginia, Detroit Publishing, about 1905.

In 1928, the Chamberlin-Vanderbilt Hotel was built on the same site, financed by local businessmen headed by seafood magnate James Darling of Hampton. The nine-story Georgian-style hotel’s name was changed to the Chamberlin Hotel in 1930 after a local hotel company bought out the Vanderbilt interest. With the onset of the Great Depression, the hotel passed through several owners.

For many years, Chamberlin was the only resort hotel on the Chesapeake Bay. Many of its guests arrived by steamship or train in the 1930s and 1940s. Once there, they enjoyed the lavish dining facilities and numerous leisure activities, such as indoor and outdoor pools, a health club, a bar, and small concerts. The hotel also had its own bakery, ice-manufacturing machines, and laundry facilities.

In 1942, during World War II, the Navy Department took over the Hotel Chamberlin to house officers and their families. During that time, the two decorative cupolas were taken down to prevent enemy pilots from using them as sights to bomb the fort. They were never replaced after the war.

In 1947, the War Department returned the property to civilian control, and Richmond Hotels acquired it.

In about 1960, the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad discontinued its line to the Chamberlin, and in 1961, the Baltimore Steamship Wharf was demolished. The hotel faced heavy competition with decreasing patrons and the construction of the nearby Interstate 64. At this time, a motor entrance was built on the ground level, eliminating the grand stairs that had once led to the main public area of the lobby. Business continued to decline, leaving the upper floors unoccupied and the Chamberlin completely closed during the weekdays in the winter months. In 1979, Vernon E. Stuart purchased the hotel and began extensive renovations, especially on the upper levels.

The Chamberlin closed after the 9/11 terrorist attacks resulted in greater security at Fort Monroe, limiting public access. After deciding to close Fort Monroe as a military installation, the Chamberlin was rehabilitated and reopened in 2008 as a retirement home for “waterfront senior living.”

Today, the second floor is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It has retained the hotel atmosphere, while the rest of the floors have been renovated and turned into one—and two-bedroom apartments.

In 1907, the Coast Artillery School and the U.S. Army Coast Artillery Corps were established. New buildings were constructed for classrooms and barracks, with the library and school buildings completed in 1909. The school operated until 1946 when most of the coast artillery was disbanded, and it was moved to Fort Winfield Scott in San Francisco, California.

During the Spanish-American War, the Camp Josiah Simpson Army General Hospital, including the post-hospital and a tent camp, was established on Fort Monroe’s parade ground.

During World War I, Fort Monroe and Fort Wool were utilized to protect Hampton Roads and the Chesapeake Bay area’s important inland military and civilian resources. In February 1917, the fort installed the first anti-submarine net in America stretching to Fort Wool.

Fort Monroe was also important as a mobilization and training center. In 1918, Fort Eustis was established near Newport News to relieve overcrowding at Fort Monroe. During the war, the authorized strength of the Coast Defenses of Chesapeake Bay was 17 companies, including five from the Virginia National Guard.

During World War II, Fort Monroe remained the headquarters for the Harbor Defenses of Chesapeake Bay. However, new 16-inch gun batteries were built at Fort Story and Fort John Custis on Cape Charles, making Fort Monroe’s heavy guns obsolete. Between 1942 and 1944, all of the fort’s 10-inch and 12-inch guns and mortars were scrapped.

By the war’s end, the vast array of armaments guarding the Chesapeake was made obsolete due to the development of the long-range bomber and the refinement of naval aviation. Essentially, all United States coast defense guns were scrapped by the end of 1948.

Since World War II, Fort Monroe has been a major Army training headquarters. In 1946, Battery Irwin became a saluting battery with two 3-inch M1902 guns relocated from Fort Wool, which are still in place. The fort also hosted some Cold War anti-aircraft defenses in the 1950s: a battery of four 90 mm guns from 1953–55 and a Nike missile battery headquarters from 1955–60. The headquarters of the Continental Army Command was established at Fort Monroe in 1955 and remained there until 1973. Afterward, the fort held the United States Army Training and Doctrine Command until it was moved to Fort Eustis.

At the turn of the 21st century, Fort Monroe supported a work population of 3,000, including 1,000 people in uniform. The Base Realignment and Closure Commission of the Department of Defense released a list of military installations in May 2005. Fort Monroe was deactivated on September 15, 2011, and many of its functions were transferred to nearby Fort Eustis. In November 2011, portions of Fort Monroe were proclaimed a national monument.

Within Fort Monroe’s 565 acres are 170 historic buildings and nearly 200 acres of natural resources, including eight miles of waterfront, 3.2 miles of beaches on the Chesapeake Bay, 110 acres of submerged lands, and 85 acres of wetlands. It also has a 332-slip marina and shallow water inlet access to Mill Creek, suitable for small watercraft.

Fort Monroe, Virginia Visitor’s Center by Kathy Alexander.

The Casemate Museum opened in 1951, depicts the history of Fort Monroe and Old Point Comfort, with special emphasis on the Civil War period.

Batteries Irwin, Parrott, De Russy, the northeast bastion battery, and Battery Anderson/Ruggles are intact, though the seaward earth cover has been removed from some of them.

Several historic weapons are preserved at the fort. The 15-inch Rodman prototype “Lincoln gun” is on the parade ground. A 90 mm gun on a dual-purpose coast defense mount remained at Battery Parrott, and two 3-inch M1902 seacoast guns remained at Battery Irwin. A 75 mm gun, nicknamed a “French 75” and used by the field artillery in World War I through early World War II, is at the new officers’ club in the northern part of the reservation.

A Visitors and Education Center was developed in the former Coast Artillery School Library, which houses fort history exhibits, public restrooms, a bookstore, and archives. It is located at 30 Ingalls Road, next to the former Post Office, which houses the offices for the Fort Monroe Authority.

The massive fort that exists today and the smaller forts that preceded it have guarded and defended Hampton Roads, one of the world’s largest natural harbors.

A partnership between the Fort Monroe Authority, the National Park Service, and the City of Hampton manages Fort Monroe.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2024.

Also See:

The Old Dominion – Settling Virginia

Sources:

City of Hampton

Encyclopedia Virginia

Encyclopedia Virginia – 2

National Park Service

Port Monroe Authority

Virginia Places

Wikipedia