“When I landed on the soil, I looked on the ground, and I says this is free ground. Then I looked on the heavens, and I says them is free and beautiful heavens. Then I looked within my heart, and I says to myself I wonder why I never was free before?”

— John Solomon Lewis, on his arrival in Kansas

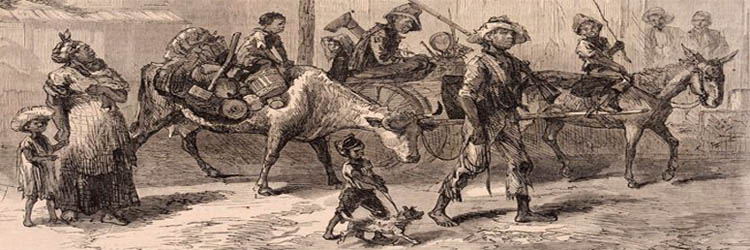

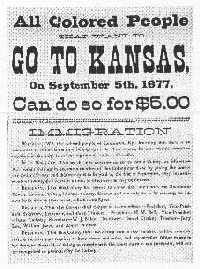

When the last Federal troops left the southern states in 1877, Reconstruction gave way to renewed racial oppression and rumors of the re-institution of slavery. Fearful for their lives, many African Americans began to flee the South for Kansas in 1879 and 1880 because of the state’s fame as a Free-State and the land of the abolitionist John Brown. These many people were called Exodusters.

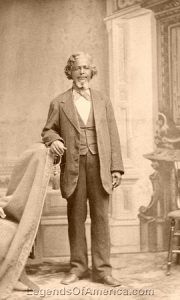

The Kansas Exodus was an unorganized mass migration that began in 1879, led by several men, including Benjamin “Pap” Singleton. Though local relief agencies, such as the Kansas Freedman’s Relief Association, tried to provide aid, they could never do enough to meet the needs of the impoverished refugees. Appleton’s Annual Cyclopedia for 1879 summarized it somewhat like this:

“The attention of the country during the past year has been attracted to the movements among the African-American population, chiefly in the states bordering on the Mississippi River. There was no appearance of organization or system among these people — their irregularity and absence of preparation indicating spontaneity and earnestness. Bands moved from the plantations to the Mississippi River and then to St. Louis and other cities, with no defined purpose, except to reach a state west of the Mississippi River, where they expected to enjoy new prosperity. Their movements received the name of the ‘Exodus.'”

Various theories have been advanced to account for this unusual course by African-Americans. Some contended that the exodus was due chiefly to the loss of political power by the blacks at the end of the reconstruction period. Others insisted unscrupulous politicians instigated the African-Americans in some of the Northern states with the hope of securing their support in close elections. Another theory was that land speculators in the new states west of the Mississippi River circulated alluring reports in the Lower Mississippi Valley. The promise of “Forty acres and a mule” was too tempting for them to withstand.

But the chief cause of the discontent among the blacks, and the one who led them to emigrate, was probably stated by Governor Stone of Mississippi in his message to the legislature of that state in 1880, when he said: “A partial failure of the cotton crop in portions of the state, and the un-remunerative prices received for it, created a feeling of discontent among plantation laborers, which, together with other extraneous influences, caused some to abandon their crops in the spring to seek homes in the West.”

However, one influence at work, which was not considered by the theorists of the time, was the influence wielded by blacks who had found homes in the North and West, as written in their letters to friends and relatives in the South. One of these men was Benjamin “Pap” Singleton, who located in Morris County, Kansas, shortly after the war, and began the agitation for immigration as early as 1869. Singleton was president of a committee to invite African-Americans to come to “Sunny Kansas.” He was from Tennessee, visited that state in his efforts to induce the blacks there to emigrate, and in other ways was so active that he was designated as the “Father of the Exodus.” It is said that his favorite argument ran something like this:

“Hyar you all is potterin’ around in politics, tryin’ to git into offices that you ain’t fit for, and you can’t see that these white tramps from the North is simply usin’ you for to line their pockets, and when they git through with you they’ll drop you, and the rebels will come into power, and then whar’ll you be?”

Nicodemus Town Company Circular

It is not strange that Kansas — the state where the great conflict began that ended in the liberation of the slaves — should be the goal of many of the “Exodusters.” The Kansas Monthly for April 1879 referred to the movement as a “stampede of the colored people of the Southern states northward, and especially to the State of Kansas” and gave an account of a meeting held at Lawrence, which adopted a series of resolutions, one of which was as follows:

“In view of the fact that large numbers of these immigrants are arriving in Kansas in a destitute condition and need our aid and direction to enable them to become self-sustaining, we believe that a state organization for this purpose should be effected at the earliest possible moment, and this philanthropic work in the hands of an efficient and responsible state executive committee.”

As a result, the Freedman’s Relief Association was established in May 1879.

At various points in the South, conventions of African-American men were held to discuss the exodus. One of these met at New Orleans, Louisiana, on April 17, 1879, and of the 200 delegates, about one-third were preachers. It was a turbulent meeting but finally adopted a resolution “that it is the sense of this convention that the colored people of the South should migrate,” and closed with an appeal to the people for material aid. Another convention, at Vicksburg, Mississippi, on May 5, 1879, asserted the right of African-Americans to emigrate where they pleased but urged those who were thinking of migrating “to proceed in their movements as reasonable human beings, providing in advance by the economy the means for transportation and settlement, sustaining their reputation for honesty and fair-dealing by preserving intact, until completion, contracts for labor-leasing which have already been made.”

The convention also deplored the circulation of false reports to the effects that lands, mules, and money were awaiting the emigrants in Kansas and elsewhere “without labor and without price.” Two days after the Vicksburg Convention, many black men assembled at Nashville, Tennessee, with several African-Americans from the Northern states present.

The resolutions of this convention were highly radical, demanding social and political equality for black people; opposing separate schools for the races; recommending that several state legislatures enact laws providing for compulsory education, and asking Congress to make an appropriation of $500,000 to defray the expenses of the African-Americans of the South “to those states and territories where they can enjoy all rights which are guaranteed by the laws and constitution of the United States.”

By the close of the year 1879, several thousand people had found their way into Kansas. On April 1, 1880, Henry King, then postmaster at Topeka, Kansas, wrote to Scribner’s Magazine:

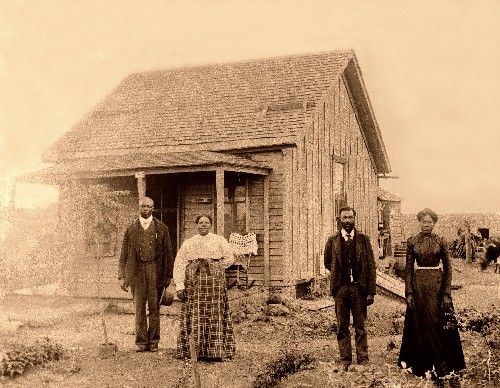

“There are, at this writing, from 15,000 to 20,000 colored people in Kansas who have settled there during the last twelve months — 30 percent of them from Mississippi; 20 percent from Texas; 15 percent from Tennessee; 10 percent from Louisiana; 5 percent each from Alabama and Georgia, and the remainder from the other Southern states. Of this number, about one-third are supplied with teams and farming tools and may be expected to become self-sustaining in another year… The area of land bought or entered by the freedmen during their first year in Kansas is about 20,000 acres, of which they have plowed and fitted for grain-growing 3,000 acres. They have built some 300 cabins and dugouts, counting those which yet lack roofs and floors, and in the way of personal property, their accumulations, outside of what has been given to them, will aggregate perhaps $30,000. It is within bounds to say that their total gains for the year, the surplus proceeds of their efforts, amount to $40,000, or about $2.25 per capita.”

This was accomplished by one-third of the emigrants; of the other two-thirds, about half of them were congregated in the towns, and the other half had found employment as farmhands in various parts of the state. Still, only about one out of every twenty had become the owners of small homesteads.

In 1880, the U.S. Senate appointed a committee of five to investigate the causes of the exodus. Testimony was taken to make a volume of nearly 1,700 printed pages. The majority report held that the exodus had been brought about to colonize the blacks in some Northern states for political purposes. However, the evidence would hardly bear out that theory.

An effort was made to show that Governor John P. St John had been instrumental in inducing many blacks to locate in Kansas. Still, one of the colored witnesses, formerly of Texas, produced a letter from the governor in which he said: “If your people are desirous of coming to Kansas, I advise you to come in your private conveyances and bring your household goods and plows… But I want to impress this one fact on your people who are coming to Kansas, that you must not expect anything, as we hold out no inducements to whites or blacks.”

The exodus continued into 1880, and the failure of crops in South Carolina in 1881 caused several blacks to leave the state in the fall of that year, a few of them coming to Kansas. Another migration occurred in 1886, but it was insignificant compared to 1879.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander, updated May 2023.

Also See:

Nicodemus – A Black Pioneer Town

Source: Blackmar, Frank W.; Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912.