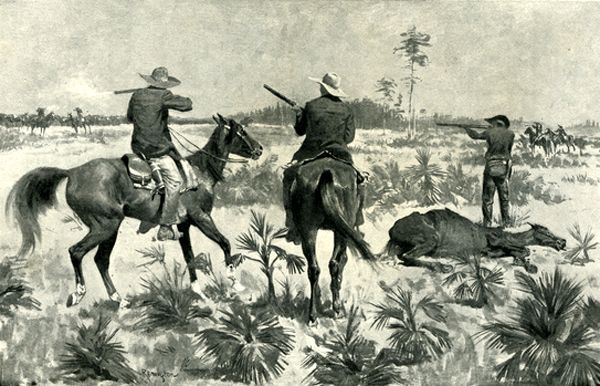

Cracker Cow Hunt, by Casper McCloud, 1993, courtesy Florida Historical Society.

“I was sitting in a “sto’ do’” (store door) as the “Crackers” say, waiting for the clerk to load some “number eights” (lumber), when my friend said, “Look at the cowboys!” This immediately caught my interest. With me cowboys are what gems and porcelains are to some others.” – Frederic Remington, 1895

The chief tool of the Florida cowboy in the 18th century was a strong whip, and when he cracked it to herd the cattle along, it sounded like a gunshot. These whips were 12 to 18 feet of braided buckskin fastened to a handle of 12-15 inches long. As a result of this sound, which sometimes resounded for several miles, these cowboys were called “crackers.”

Early on, Spain attempted to colonize Florida’s interior, and by 1700, Florida contained approximately 34 ranches with 20,000 head of cattle. However, when the British and Creek Indians began to raid the ranches in 1702 and 1704, the devastated Florida cattle ranchers abandoned their land. They retreated to the fortress towns of St. Augustine and Pensacola, leaving behind massive herds of Andalusian cattle.

After the cattle were left behind, they multiplied and spread across the land. These cattle, which were prized for their hardiness and resistance to parasites, were the ancestors of today’s modern Texas Longhorns.

In about 1750, Seminole Chief Ahaya led his people from northern Florida to Paynes Prairie to escape encroachment by English colonists. There, he and his band settled on an abandoned Spanish cattle ranch and began to gather the wild cattle into a vast herd, earning Ahaya the nickname “Cowkeeper.” Cattle became the new chief base of their economy; they remained Florida’s major livestock producers throughout most of the 1700s. The village he and his people established, called Cuscowilla, was located at present-day Micanopy.

When the English took over Florida in 1763, early settlers and the Creek Indians also owned and managed substantial herds. Soon, cowmen from Georgia and the Carolinas spread into north Florida.

Early on, the Europeans, Americans, and the Indians fought to control the large, wild herds of the interior and the land they grazed on. It was then that the cattlemen rounding up the loose cattle used long, braided leather bullwhips to bring cattle out from the underdeveloped forest brush. They flailed whips with so much force that the tips created a loud cracking sound. Thus, a name for these Florida cowboys was born.

Later, the groups fighting over the wild cattle began to steal cattle from each other, and by the second half of the 18th century, cattle rustling was widespread. Rustling was one of the elements that led to the Seminole Wars.

When the U.S. took possession of Florida in 1821, the territory was described as a “vast, untamed wilderness, plentifully stocked with wild cattle.” These cattle were descended from a mix of Spanish and British breeds and were hardy animals that survived on native forage, tolerated severe heat, insect pests, and acquired immunity to many diseases.

Decades before the cowboys of Texas were driving cattle through Oklahoma and Kansas on the Chisholm Trail, the Florida Crackers were spending weeks or months on cattle drives across difficult marshes and dense scrub woods, from central Florida to Jacksonville, Savannah, Georgia, and Charleston, South Carolina. Along the way, they often endured burning heat, torrential thunderstorms, and hurricane winds and were forced to fight off panthers, wolves, bears, and cattle rustlers.

In 1842, Florida passed the Armed Occupation Act, which provided grants of 160 acres as an incentive to populate Florida. This act drew cattlemen in great numbers from Georgia, Alabama, and the Carolinas, who homesteaded 200,000 acres. Some seized range territory that the Seminole Indians had been forced to relinquish during the Seminole Wars. Few of the new settlers owned grazing land since there was an extensive open range.

The number of cattle increased rapidly from the 1840s until the Civil War, and Florida became second only to Texas in per capita value of livestock in the South.

The cattle drove Florida’s economy for much of the 19th century. By 1850, the 120-mile Cracker Trail had been blazed following an east/west route across Florida from Fort Pierce to Bradenton. The Kissimmee River’s moist land prevented travel to the north, while the sizable Lake Okeechobee and the Everglades swamps prevented travel to the south. Though Florida’s early settlers used the trail to traverse the state, it was primarily used to drive cattle from Florida’s heartland to the coastal ports for shipment, mainly to Key West and Cuba. The cattle had to be delivered to shipping ports during peak market season in late July and August when the weather was at its worst to maximize profits.

Cracker cowboys, sometimes called “cow hunters,” were distinct from the Spanish vaquero and the Western cowboy, as they did not use lassos to herd or capture cattle but instead utilized herd dogs to move cattle along the trail. They rode short horses called “cracker ponies,” and their cattle, known as “cracker cows,” were smaller than the western breeds. Florida Crackers also became distinguishable by the architecture of their frontier homes, musical traditions, and lifestyles.

During the Civil War, cracker-supplied cattle were the Confederate Army’s chief source of meat, leather, and hides, particularly after Union ships blockaded southern ports. The “Cow Cavalry” was organized to protect herds from Union raiders. Forced to drive the animals by land into Georgia, the “Cow Cavalry” faced harsh conditions and the occasional skirmish with Union forces, prompting some to turn sides and sell their cattle to the Union-controlled port of Fort Myers.

After the Civil War, trade boomed with Cuba, Key West, and Nassau, and Florida became the nation’s leading cattle exporter. The commerce provided income to cattlemen, merchants, and shippers and contributed to the state’s recovery from the Reconstruction-era depression.

By the 1890s, cow camps were located in most sections of the state, and cattle drives continued into the 20th century until fencing laws were introduced in 1949, ending the era of the open range. One of the last drives along the Cracker Trail took place in 1937.

Today, raising cattle is still one of the state’s biggest businesses, with Florida’s ranchers raising the third-largest number of cattle of any state east of the Mississippi River.

The cracker cowboys are remembered along the Florida Cracker Trail designated as a “Millennium Trail” in 2000, which recognizes both its historical and cultural importance to the state and the nation. The trail’s western terminus is at Manatee Village Historical Park in Bradenton, and its eastern end at Fort Pierce. Today the trail includes parts of State Road 66, State Road 64, and U.S. Highway 98. An annual Cracker Trail ride is conducted in February of each year by the Florida Cracker Trail Association members.

Along the trail, travelers can still visit the Desert Inn and Restaurant in Yeehaw Junction built in 1885 as a saloon for weary crackers and travelers, with a brothel on the second floor. Another great stop along the trail is P.P. Cobb’s General Store in Fort Pierce, where crackers often stopped. Built in 1882, it is the oldest commercial establishment in St. Lucie County. The Cracker Trail Museum in Zolfo Springs provides a wealth of information regarding the trail and the cracker cowboys.

More of Florida’s cowmen’s culture can be found in numerous rodeos that bring crowds to Arcadia, Homestead, Bonifay, and dozens of other rural areas. In Kissimmee, the Silver Spurs Rodeo is the largest rodeo east of the Mississippi River.

Today, among some Floridians, the term “cracker” is used as a proud self-description to indicate that their families have lived in the state for many generations. It is considered a source of pride to be descended from frontier people with the grit and tenacity of those laboring cowboys.

© Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2021.

Also See:

Sources:

Florida Memory

Tampa Magazines

University of South Florida

Wikipedia