By Addison Erwin Sheldon, 1913

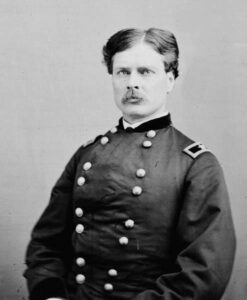

The Battle of Beecher Island, also known as the Battle of Arikaree Fork, was an armed conflict between the United States Army and several Plains Indian tribes. Occurring on September 17, 1868, it was one of the most brutal battles between the white men and the Plains Indians in the American West. It occurred on the Arikaree River, then known as part of the North Fork of the Republican River, near present-day Wray, Colorado. Afterward, the battle was named for Lieutenant Fredrick H. Beecher, an army officer killed during the battle.

Fifty-one scouts and frontiersmen under the command of Colonel George A. Forsyth stood off, on a little sandbar in the river, the combined forces of the Northern Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Oglala Sioux for nine days. They lost over one-third of their men killed and wounded, while the Indian loss was many times as great.

These Indians had been murdering the settlers and travelers in western Nebraska and Kansas for months. Soldiers were sent to pursue them but always arrived on the scene of their action after the Indians were gone, finding nothing but the melancholy duty of burying the murdered citizens.

Forsyth raised a company of 50 frontiersmen, many of whom had lost their dearest friends and relatives to the Indians. Some of them were noted scouts. All of them enlisted to fight.

Early in September, this small command started from the place of the latest Indian murder near Fort Wallace, Kansas. They struck a trail leading to the Republican River. Following the trail to Nebraska, it was joined by other trails and still others until the little party of 50 men was traveling a great beaten road, as wide as the Oregon Trail, made by thousands of Indians and ponies, and with hundreds of campfires where they stopped at night. It seemed a crazy act to follow so great a trail with so small a party, but the little band had started to find and fight Indians and kept on.

On the afternoon of September 16, the Indian signs were very fresh, and Forsyth resolved to go into camp early, rest his men and be ready to strike the Indians the next day. An extra number of men were posted on picket duty to prevent surprise. In the earliest gray of the following day, the men were up and saddling their horses when there came a volley of shots from the pickets, followed by the yell and rush of Indians. The attackers expected to find the soldiers asleep and their horses out feeding. They planned to stampede the horses and leave the soldiers on foot in the open prairie where they could quickly surround them and cut them off. However, they found their horses saddled, every scout ready with his rifle, and soon retreated from the white men’s bullets. As daylight broke, Grover, the head scout, exclaimed, “Look at the Indians!” The hills on both sides of the little valley swarmed with them. None of the scouts had seen so many hostile Indians in one group.

Forsyth saw the situation at a glance. A few hundred yards away, in the middle of the river, was a sandbar island having one cottonwood tree and a growth of willows. It was the only cover in the valley. The scouts dashed forward through the water to the island at the word of command. Every man tied his horse firmly to a willow bush and, dropping on his knee, held his rifle in one hand and dug a hole in the sand. This move was a complete surprise to the Indians. They had expected to eat up the little band in one mouthful. They now saw them making a fort out of the little island. The Indians crowded up to the bank on both sides of the river and filled the air with bullets and arrows. A number of the scouts were killed and wounded, while the poor horses plunged and struggled in misery until they fell in death.

The fire of the Indians was very hot and accurate. Colonel Forsyth had his leg broken by a bullet, and his second in command, Lieutenant Frederick H. Beecher, a nephew of Henry Ward Beecher, was killed. Forsyth cut the bullet from his leg, which he bandaged with his own hands, telling his men to be steady, help each other, and make every shot count. In an hour, the men became calmer. They were getting a good cover with sand and dead horses. Whenever an Indian showed himself within range, a bullet went after him. This discouraged the Indians so much that they drew back, while the scouts took the time to care for the wounded and throw up more sand.

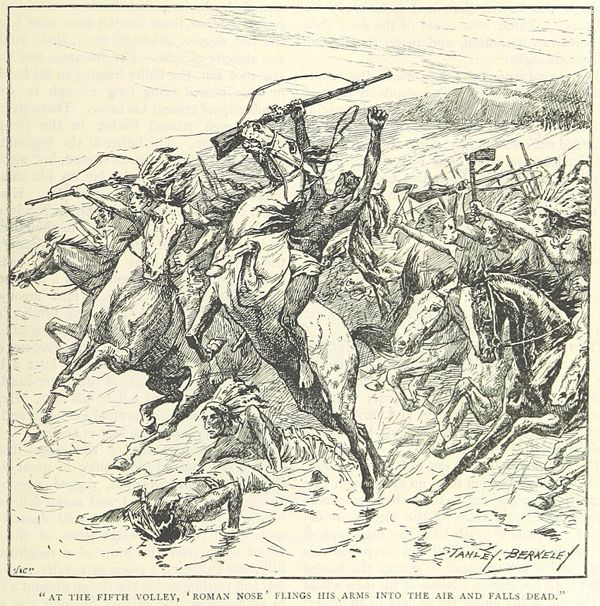

About noon, there was a great gathering of Indians on the hill in sight of the scouts. Warriors came riding in from all parts of the field. Among them was one whom every scout knew at a long distance. He was Roman Nose, over six feet tall, the tallest Indian on the plains, and one of their greatest chiefs. It was evident a big plan was underway. The council broke up, and the plan appeared. Roman Nose led a group of mounted young men out into the valley. Others joined them. They drew together in a line facing the island with Roman Nose at the head. The plan was now clear. This chosen body of two or three hundred was to charge straight on the island while the rest of the Indians crept up through the grass and fired as fast as they could at the scouts in their sand pits to distract their attention.

The death of Roman Nose (aka Hook Nose) at the Battle of Beecher Island depicted in a book from 1895.

Roman Nose gave the signal, and his horsemen started for the island. Forsyth had ordered his men not to fire until the first pony reached the river’s edge. The scouts were armed with a new gun, the Spencer Seven-shooter Carbine. The Indians knew what a one-shot rifle was but had never seen one that shot seven times without loading. On came the line of Indians, yelling and whipping their horses.

Just at the river’s bank, the rifles of the scouts flashed from the sandpits, and groups of riders fell from their ponies. On they came. Another volley and more Indians fell. Another, and another and another and another, with a steady aim and terrible effect. Roman Nose fell dead from his horse, and the Indian line broke and scattered. Forsyth turned anxiously to his scout Grover. “Can they do any better than that?” he asked. “I have been on these plains, boy, and man, for twenty years, and I never saw anything like it,” answered the scout. “Then we have got them,” replied Forsyth.

The battle now changed to a siege, while from the hills arose that most harrowing of all sorrowful cries, the wail of the Indian women for their dead. Through many hours this haunted the ears of the men on the island. There were no more attempts to take the island by storm. Starvation was the Indian plan. At the first of the fight, the scouts had lost their pack mules with all their provisions. They had nothing but river water and a dead horse. After dark, attempts were made to creep through the Indian lines and carry word to the railroad a hundred miles away. One attempt failed. The Indians were too watchful. Another attempt was made; two scouts emerged in the darkness and did not return. Those left on the island could not know whether their messengers were dead. They could only hope and watch the line where the sky and prairie met. They lay in their sand pits for a week, drank river water, and ate horse meat. The hot sun glared from the sky, the smell of the dead filled the air, the flies buzzed, and the Indians glided stealthily about the hills. A little charge would have captured the island now, but the Indians had suffered too much to try again. They preferred to starve the scouts.

In the forenoon of September 25, a dark moving patch appeared far off on the prairie. It grew larger until the watchers saw that it was an ambulance and a column of cavalry. They knew then that the battle and the siege of Beecher Island were over. The Indians fled as the soldiers came near, and soon the starving and wounded were being cared for.

General George Custer said that the Arickaree fight was the most significant battle on the plains. At Wounded Knee, South Dakota lived a tall wise Sioux named Fire Lightning. He was in the Arickaree fight and told me this story one summer afternoon, sitting in the shadow of his log house and looking out upon his garden. He said the Indians lost nearly a hundred men in the fight and showed by gestures with his hands how fast the white men fired from their sandpits and how Roman Nose fell from his horse.

Today a monument has been established at the site of the Beecher Island Battle. The Beecher Island Battlefield Monument is a joint Colorado-Kansas historical site established in 1905 to commemorate the September 17-19, 1868 battle fought between Colonel George A. Forsyth’s Scouts and a group of about 750 Indians from several Plains Indian tribes. Chief Roman Nose died in the battle. The memorial is located 20 miles south of Wray, Colorado.

The monument that stands today is the second to be erected. The original monument, located about 200 yards south of today’s marker on the original island, was washed away in the 1935 Arickaree River flood. Only part of the engraved portion of the base of the original marker was recovered.

By Addison Erwin Sheldon, 1913. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated July 2023.

Beecher Island Memorial, Colorado

About the Author: Excerpted from the book, History and Stories of Nebraska by Addison Erwin Sheldon, 1913. Addison Erwin Sheldon (1861-1943) was director of the Nebraska Historical Society and wrote numerous books devoted to the history of Nebraska. Sheldon also took and drew many of the photographs and illustrations in his many texts. The text here, however, is not verbatim, as it has been heavily edited and additional information added.