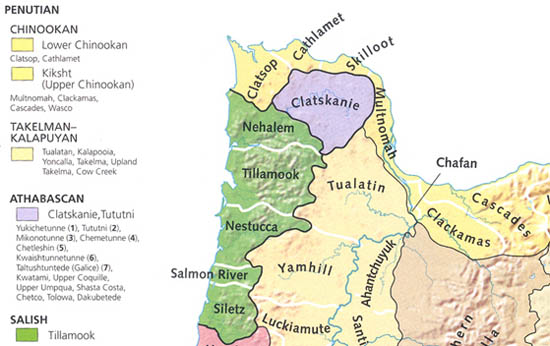

The Chinookan peoples include several groups of Native Americans of the Pacific Northwest who shared closely related Chinookan languages and traditionally lived in Washington and Oregon, from the mouth of the Columbia River to The Dalles.

The Chinookan people were relatively settled, living in villages along the banks of the Columbia River and near the mouths of its tributaries. Their villages varied in size, sometimes with only a few houses. In each village, there was always a headman or chief, who sometimes extended his influence over several neighboring villages, but in general, each settlement was independent.

Here, they hunted elk, deer, and bear and fished, with salmon as the mainstay of their diet. The women gathered and processed many nuts, seeds, roots, berries, and other foods. However, they did move around in the summer for additional hunting and fishing expeditions. The falls and Cascades of the Columbia and the falls of the Willamette River were the chief points of gathering in the salmon season.

They resided in longhouses where as many as 50 people or more, related through extended kinship, lived together. These longhouses were made of red cedar tree planks, measuring 20-60 feet wide and 50-150 feet long. Inside, they slept on reed mats over raised boards.

Owing partly to their settled living patterns, the Chinook and other coastal tribes had relatively little conflict over land. They did not migrate through each other’s territories and had rich natural resources.

The Chinooks were superb canoe builders, navigators, masterful traders, skillful fishermen, and planters. They were famous as traders, with connections stretching as far as the Great Plains, where they traded dried fish, slaves, canoes, shells, hair and clothing ornaments, and more. An annual trade fair at The Dalles was the largest in Western North America, and any movement of materials between the coast and the fair passed through Chinookan territory. Their canoes were hollowed out of single logs, often of great size and well-made.

Social classes marked the tribes’ societies. The upper classes, a minority of the community, included shamans, warriors, and successful traders. These people practiced social discrimination, limiting contact with commoners and forbidding play between children of different social groups. The elite of some Chinookan tribes practiced head binding — flattening their children’s forehead and the top of the skull as a mark of social status. This was affected by binding an infant’s head under pressure between boards when it was about three months old and continued until the child was about one year of age. Flat-headed community members had a rank above those with round heads and refused to enslave other persons who were similarly marked. They were later called “Flathead Indians” by early white explorers.

Slaves were usually obtained by barter from surrounding tribes, though occasionally were gained in successful raids made for that purpose. Some historians have estimated that as many as 25% of the area’s population were slaves. Free people were divided into a relatively powerful elite and commoners who were household members but exercised little or no power.

Traditional Chinook religion focused on the first-salmon rite, a ritual where each group welcomed the annual salmon run. Another important ritual was the individual vision quest, an ordeal undertaken by all male and some female adolescents to acquire a guardian spirit that would give them hunting, curing, or other powers, bring them good luck, or teach them songs and dances. Singing ceremonies were public demonstrations of these gifts.

In disposition, they are described as treacherous and deceitful, especially when their greed was aroused. The making of portages at the Cascades and The Dalles by the early traders and settlers was often accompanied by much trouble and danger.

By the late 1700s, Spanish, American, and British voyagers often encountered the Chinook tribes.

The Chinook were documented when they were encountered by American explorers Lewis and Clark in 1805 and again on their return up the river in 1806.

In the fall of 1805, as the Corps of Discovery began to make its way down the Columbia River after crossing the Rocky Mountains, they were told by the Nez Perce that the Chinook living down the river had a different culture and language than anything the Corps had encountered. The Nez Perce chiefs also warned the captains of a rumor that the Chinook intended to kill the Americans when the expedition arrived. However, the expedition continued.

The Chinook were accustomed to European goods and white traders; their first encounters with the expedition were peaceful. On October 26, 1805, two Chinook chiefs and several men came to the expedition’s camp to offer gifts of deer meat and root bread cakes. The captains responded by presenting the chiefs with medals and the men with trinkets.

“All go lightly dressed wearing nothing below the waist in the coldest weather, a piece of fur around their bodies and a short robe compose the sum total of their dress, except a few hats and beads about their necks, arms, and legs.”

— William Clark

Lewis and Clark received similar receptions as they approached the Pacific Ocean along the Columbia River. However, the expedition suffered from the theft of supplies. This became such a problem that the captains had to restrain some men from instigating fights with the Indians.

Because of these issues, the Corps decided to spend the winter on the south side of the river, where the Clatsop lived, rather than on the north bank among the lower Chinookan bands. During their stay at Fort Clatsop, visits by the Chinooks were limited, and the Indians were not allowed to stay in the fort overnight. Both captains’ journals noted low opinions of the Chinookan customs and appearance.

When Meriwether Lewis met with one of the Chinook chiefs, the Indian blamed the trouble on a select few and reassured Lewis that the captain of his village wished for peace.

“I hope that the friendly interposition of this chief may prevent our being compelled to use some violence with these people; our men seem well disposed to kill a few of them.”

— Meriwether Lewis documented after he met with the Chinook chiefs

Tensions were eased only temporarily until another theft occurred. However, the expedition continued passed the falls of The Dalles and returned to Nez Perce country without having fired at a native.

By this time, the estimated population of the Chinook in the valley was as high as 10,000 in the spring and summer. But their population would decline in the following decades as more and more Americans pushed westward.

In 1824-25, epidemics such as smallpox and malaria struck the Northwest Coast Native peoples. By 1830, villages near Fort Vancouver were nearly abandoned, and Chinook Chief Comcomly died that year when a fever epidemic struck his tribe.

That decade saw several missionaries enter the territory who established missions amongst the Chinook of the Lower Columbia. More missionaries followed, and in 1844, another epidemic hit the Northwest — dysentery. By the following year, missionaries and traders began to outnumber the area’s indigenous populations as immigration continued and Native populations were decimated by disease. By 1850, it is estimated that only about 4,000 Chinook had survived.

Treaties with the Chinook and other tribes began in 1851, even though Congress had acknowledged Indian title to their lands in the 1848 Organic Act. Though the tribes signed the treaties in good faith, Congress never ratified them. As a result, the land on the coast that was taken from them and opened to settlement was illegally obtained.

Though Congress did ratify several treaties between 1853 and 1855, the treaties did not include traditional rights, such as hunting and fishing in accustomed places. Instead, they reserved for the tribes only small remnants of their traditional homelands. They provided for payment of only a few pennies per acre for the land taken, which was paid in annuities over 20 years.

As a result, Indian-white relations became especially tense, particularly in those areas where strikes of gold were attracting miners. Violence broke out sporadically, perpetrated mainly by whites against Indians as miners and settlers organized themselves into militias who committed atrocities such as sacking non-combatant villages; killing old men, women, and children; and burning houses to the ground.

In the subsequent decades, the tribes were pushed onto reservations. The Chinook hired its first lawyers to fight for land rights in 1899, as the U.S. Government never compensated the tribes for the lands they took. Their legal battles continue in various forms today as the Chinook push the U.S. Government to honor their promises.

In 1911, the Chinook received allotments, and the reservations were broken up. By this time, there were only about 1,000 Chinook remaining.

Today, some Chinookan-speaking people are part of federally recognized tribes, including the Yakama Nation, the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation, the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community, and the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians Indians. However, the Chinook Indian Nation, consisting of the five westernmost Tribes of Chinookan peoples, including the Lower Chinook, Clatsop, Willapa, Wahkiakum, and Cathlamet, are still working to obtain federal recognition.

Under President Bill Clinton, the Chinook Nation gained Federal Recognition in 2001 from the Department of Interior. However, after President George W. Bush was elected, his political appointees reviewed the case and, in a highly unusual action, revoked the recognition in 2002. In 2008 and 2009, the Chinook Nation sought Congressional support for recognition by the legislature, and Bills were introduced, which unfortunately died in Congress.

The Chinook Indian Nation continues to engage in a continuing effort to secure formal recognition, conducting research and developing documentation to demonstrate its history. Without federal status, the Chinook People do not have the resources to help their citizens, such as Eldercare, health care, housing, or education benefits. Their population is estimated to be about 3,000 Chinook descendants.

Despite these obstacles, they continue the campaign to correct their federal status and have offices in Bay Center, Washington.

The tribe holds an Annual Winter Gathering at the plank house in Ridgefield, Washington, and an Annual First Salmon Ceremony at Chinook Point (Fort Columbia) on the North Shore of the Columbia River.

More Information:

Chinook Nation

3 E. Park Street

P.O. Box 368

Bay Center, WA 98527

360-875-6670

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2023.

Also See:

Native American Photo Galleries

Native Americans – First Owners of America

Sources:

Encyclopedia Britannica

Department of History at Portland State University

Hodge, Frederick Webb, Compiler. The Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico. Bureau of American Ethnology, Government Printing Office. 1906.

Oregon History Project

Public Broadcasting System

Wikipedia