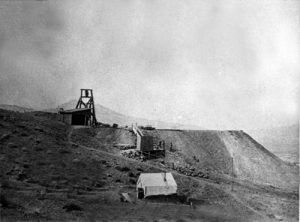

A scene of Greenwater shortly before the townsite merger. The buildings were soon moved to Ramsey’s mining camp, which was renamed Greenwater — often called “New Greenwater.”

Despite the boom fever, several firms besides the Engineering & Mining Journal managed to resist the excitement of the rush. William Clark, president of the Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad, for example, resisted the heavy local pressure to begin immediate construction of a branch line into Greenwater, and instead, more reasonably announced that the branch road would be built “just as soon as we are fully assured of the camps’ permanency.” The pressure on Clark was tremendous, for if Greenwater did turn into a productive camp, the first railroad into the district would reap enormous profits. Also, the Greenwater fever had invaded the Clark family itself, for J. Ross Clark, William’s brother, had invested in the district and incorporated the Clark Copper Company.

By the middle of November, no less than 100 people were arriving in the district every day, and still, the demand for labor far exceeded the supply. But, the district still had several rather insurmountable problems, and that same month, one of them was graphically highlighted when one of the water wagons serving the holdings tanks of the town broke down. Immediate panic ensued, and water prices shot up to $20 per barrel before the wagon could be repaired. It was a reminder that Greenwater would never become a producing district until the water and transportation problems were solved if any need be had.

By the end of November, the Greenwater stampede was of such proportions that although the district had yet to ship a single sack of ore, it was getting almost weekly coverage by the national mining journals. As one single example of the continuing boom, Thomas W. Lawson of Boston, a noted copper operator, and millionaire, purchased the Greenwater Red Boy and Greenwater Saratoga Mining Companies in late November for a reported $2,000,000 in hard cash and immediately announced plans to erect a copper smelter.

By then, the Greenwater boom was so great that the competition between the Kunze and Ramsey townsites became impractical. Kunze’s site, due to its location nearer the larger mines, and its success in obtaining a post office, a newspaper and several leading business houses, was clearly leading in the townsite race over Ramsey’s camp, but there were problems involved in Kunze’s physical location. His camp was perched up in the Greenwater Hills, practically on the end line of the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company mines, and only a wooden fence kept drunken miners from walking off the end of one of Kunze’s streets into one of the mines’ shafts.

Also, the district’s leading mine owners realized that a railroad was an absolute necessity for the future prosperity of Greenwater, and building a railroad into Kunze’s town would be difficult due to its location in the hills overlooking Greenwater Valley. Nor were the railroad interests very anxious to build directly into the heart of the mining district, for they had painfully learned at Tonopah how expensive it was to lay tracks overactive and conflicting mining claims. Thus the railroad companies, both for ease of construction and avoidance of involvement in expensive land battles, preferred to build their railheads at spots away from the actual mines. Charles Schwab, in turn, was growing uneasy at the prospect of a large town night on top of his mining claims, since that would lead to difficulties in opening up new ground when the time came. For a combination of these reasons, the district’s leading promoters decided in late November to move Kunze’s camp of Greenwater away from its present location and down into the Greenwater Valley below, where railroad construction and acquisition would be much easier and less expensive. After all, the planners at this time were expecting Greenwater to blossom into a city of thousands, rivaling the other great copper towns of the United States, such as Butte, Montana, and there simply was not enough room at Kunze’s site for such an expansion.

As a result, Harry Ramsey’s camp of Copperfield, which had never enjoyed the prosperity of Kunze’s, suddenly found itself saved. A new Greenwater Townsite company was incorporated, which bought out the interest of both Ramsey and Kunze in their old townsites, and backed by the capital of the leading mining promoters, announced that the entire Kunze townsite would be moved down into the valley, near Ramsey’s old site. Owners of lots in both Kunze’s and Ramsey’s old townsite would be given lots of equal value and location in the new town, and the new combined townsite would carry the name of Greenwater.

After the townsite consolidation announcement, the Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad reported that it would build a spur into the new site, and John Brock announced that he would soon start construction on a $60,000 hotel. However, all was not well for with the coming of winter; although mild snowfalls helped alleviate the water shortage, the cold weather immediately pointed out another serious supply problem in the district. Wood was almost unavailable as fuel to warm the district’s tents and buildings, and Greenwater residents began to experience a “lively skirmish to get enough greasewood to keep warm.”

Then, just to keep the townsite situation from becoming too calm, Patsy Clark decided to promote his townsite of Furnace, and ads began running in the Rhyolite newspapers. Lots were on sale, according to the ads, for $250 to $750 apiece, and over $30,000 worth of lots had already been sold. The ad also proclaimed, “Furnace Will Be the Metropolis of The Greenwater District.”

But, wherever they were located, and whatever they were called, all the towns of the district continued to expand. The Southern Nevada Telegraph and Telephone Company completed the extension of its telegraph lines into the district in mid-December and promised that the telephone lines would soon be finished as well. Several hopeful individuals were sinking wells, and water was struck in one, eighteen miles from town. The Greenwater Townsite Company began laying pipe from Greenwater Springs to the townsite, although the flow of that spring was nowhere near enough to accommodate the demand.

By the end of 1906, with the district’s population pushing 1,500, the boom was finally slowing down. However, everyone blamed the unprecedented cold weather rather than any abatement of the Greenwater fever. Several snowstorms in late December caused much suffering, and the price of greasewood, which became increasingly scarce, rose to $15 a wagon load. Twenty loads, it was reported, were necessary to equal the burning power of a normal cord of wood.

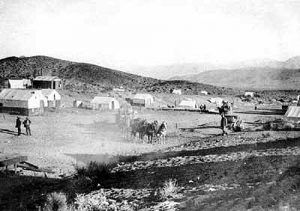

The cold weather stopped work on most of the mines, for only those whose shafts were deep enough to escape the effects of the weather were able to continue work. Still, nine more mining companies were incorporated in the district in December, bringing the total to 50, and everyone sat back, waiting for a break in the weather so that Greenwater’s unprecedented stampede could continue. During the lull in the action, the townsite move began, and New Greenwater, “The Greatest Copper Camp on Earth,” was born.

Hard on the heels of the townsite consolidation came the news of another large merger, which set even the feverish minds of Greenwater agog. Several of the leading mine owners, realizing that the district needed a smelter to become a producer, announced the formation of a giant merger towards that purpose. On December 15th, Charles Schwab, John Brock, and some Philadelphia financiers formed the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Mines & Smelting Company. By pooling their resources, Schwab and his partners hoped to cut costs and erect a large smelting plant for the reduction of the ores from each of the mines. Although no specific site was announced, Ash Meadows immediately became the leading contender for the smelter site, due to its proximity to a plentiful water supply and the railroads.

The new company announced that it would build its own branch railroad from the mines to the smelter area, 30 miles away, and that work would immediately begin on the railroad spur, the water development at the smelter site, and construction of the smelter itself. In the meantime, although the mines involved in the merger came under the umbrella supervision of the new corporation, each would retain its separate identity and would continue to pursue its own development independently.

Spurred by this news, developments at Greenwater continued at a hectic pace. The townsite merger was being carried out, and also, Patsy Clark, who stayed outside of both the townsite and mining mergers, continued to plug his town of Furnace. By January 1, 1907, that site was described as containing stores, business houses, and a hotel. A separate stage line connected it with Amargosa, and a post office had been requested.

The new townsite of Greenwater was likewise experiencing growth, in addition to the confusion of consolidation. A second weekly newspaper, the Greenwater Miner, was started by an editor attracted to the booming district from Nome, Alaska, and several more assaying, surveying, and brokerage offices opened. January 1907 saw yet another young publication start-up, which turned out to be one of Greenwater’s unique claims to fame. On January 1st, the Death Valley Chuck-Walla’s first issue hit the streets, published by C. E. Kunze and C. B. Glasscock.

As its advertisements read, it was “A Magazine for MEN.” It was “written in a vein to please. It is entertaining as well as valuable. It exposes the crooks, the wildcats, and the frauds, and roasts the knockers.” And, as the cover declared, it was “Published on the desert at the brink of Death Valley. Mixing the dope, cool from the mountains, and hot from the desert, and putting out a concoction with which you can do as you damn well please as soon as you have paid for it. PRICE, TEN CENTS.”

The first issue of the Death Valley Chuck-Walla was especially unique, for it vividly described the total confusion inherent in the townsite move which was currently taking place. In an article aptly titled “A Town on Wheels,” the movement was portrayed: “… . . pandemonium reigns. Saloons and boarding houses, stores, and brokerage firms are doing business on the run and trying to be on both sides of the mountain at one time. A barkeep puts down his case of bottles on a knoll en route from the old camp to the new and serves the passing throng laden with bedding and store fixtures… The butcher kills a cow en route and deals out steaks and roasts to the hungry multitude hurrying back to the old camp to get the necessities for the new. Those who remain in the old camp are walking two miles to the new to get the eggs for breakfast. Those who have journeyed to the new are walking two miles to the old to get their mail and a pair of socks. Through it all, Jack Salsbury, Harry Ramsey, and the Townsite Company smile…”

The Chuck-Walla had other aspects as well. Although the editors were totally committed to boosting the Greenwater District, they also realized that the proliferation of fraudulent mining schemes would hurt the district in the long run and made it their pet project to uncover mining companies who were bilking the public. The first issue carried a long article damning the Boston-Greenwater Copper Company’s manipulations, promoted by J. Grant Lyman and his Union Securities company. Lyman had earlier been arrested in Boston for pushing stock sales for non-existent mines around the Bullfrog area, and he was doing the same at Greenwater.

By January 4th, the Rhyolite Herald was able to report that the townsite consolidation was complete. Although the district and its towns total population was not easy to estimate, since so many men were constantly thronging through the hills, the Herald estimated it at between 1,500 and 2,000. More important, however, for the development of the mining district, was the report from the Fairbanks-Morse Company that it had received orders for at least twenty hoists of various sizes for the district, which indicated that more and more companies were beginning the transition from exploration to the development stage of mining. All the district needed in order to pass from a boom camp into a permanent mining town was for one big mine to make the next step, from development into production.

New Greenwater, meanwhile, reported thriving business. The townsite company surveyed 2,200 lots in over 130 blocks at the new site and reported brisk sales. Lots on Main Street sold from $500 to $5,000 apiece, and the county supervisors of Inyo county approved the townsite plat. The continuing cold weather, however, put a damper on business, as one miner reported that it was “fiercely damnable, and we put two-thirds of the time trying to rustle greasewood enough to keep from freezing.” Despite the snowfall, water was still in short supply and was selling for $10 per barrel.

The Engineering & Mining Journal was not the only publication to wonder at the immense rush into Greenwater. The Mining World, in late January, noted that “It is too early to predict the possibilities of this district. Its remoteness from transportation facilities and water has retarded its development, but very active work is being prosecuted on about 50 different properties, notwithstanding the many difficulties encountered. During the next six months, exploratory work will have probably progressed sufficiently to determine the persistence of the ore deposits.” That was the crux: why was so much money being poured into the district, when the very existence of the ore deposits below the surface level had not yet been proven? Apparently, the boom spirit, which had been ravaging throughout Nevada and eastern California since the bonanza discoveries at Tonopah and Goldfield, reached its height at Greenwater. In addition, since copper deposits at other camps such as Bisbee and Butte had always improved with depth, everyone assumed that the same would hold true for Greenwater. Since the surface richness at Greenwater far surpassed that of any copper camp ever, who could fail to think that Greenwater could indeed become the Greatest Copper Camp on Earth?

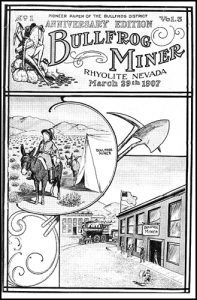

One paper, at least, did think exactly that. In late January the Goldfield Gossip printed its own assessment of the Greenwater District, and it was one which flew directly in the face of all the local predictions. “We have dissected reports from as many sources as possible regarding the future of Greenwater,” wrote the Gossip, “and all these agree that the camp would never make a production of copper to amount to anything.” As might be expected, that report caused an immediate and extreme reaction from the Greenwater papers, particularly the Death Valley Chuck-Walla, which more than adequately fulfilled its promise to “roast the knockers.” The Bullfrog Miner also scorned the Goldfield Gossip’s assessment and printed its own: “… there can be, but one future for Greenwater and that will be expressed by the six words ‘Greatest Copper Camp in the World.’”

In the end, however, no one would know for sure whether Greenwater would turn into a producer or not until the actual time arrived, and meanwhile the Greenwater District enjoyed its booming prosperity. In addition, a town government committee was organized to supervise sanitary and police measures, and Inyo County appointed a Justice of the Peace and a constable for the district.

By mid-February, the Rhyolite Herald reported that it was confident that the Tonopah & Tidewater would build a branch into the Greenwater District, and even speculated that the road would be finished by June 1st. The Death Valley Chuck-Walla in its mid-February issue, put the population of the district at 2,000, including 500 in the town of Furnace, which was beginning to emerge as a real rival to the new Greenwater townsite.

The Chuck-Walla also carried a large ad for the Greenwater Townsite Company, which optimistically forecast that Greenwater would soon be the center of three railroads. According to the ad, the district’s population was over 2,000, and two telephone and telegraph lines were doing business. “Since the first of December, lots have doubled in value. This is because there is no question whatever about the permanency and future of the place. Greenwater is destined to be the richest mineral-producing city on the whole globe.” Also, the magazine carried ads for several new Greenwater businesses.

But, as February drew to a close, there was a decided slackening in the great Greenwater boom. The district had now been opened for well over a year and had been in a boom stage for more than half that time, and as of yet, none of the companies which were sinking their shafts had found any ore under the surface which could compare with the rich surface streaks that had started the boom. While slow to dawn upon the district itself, this fact was beginning to become apparent in the national stock market.

The Bullfrog Miner noted the slight slackening of the Greenwater boom and reported that while “there is somewhat of a dullness pervading the camp, as far as the influx of people and industries is concerned, the properties are looking mighty fine.”

But, at the time, no one could have hoped to persuade a Greenwater citizen that the bloom was beginning to fade. On March 1st, the papers reported that the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Mines & Smelting Company was beginning to work on the smelter site at Ash Meadows. More immediate encouragement came from the news that Mr. Lemle was opening a sub-agency for Budweiser at Greenwater, and was arranging for daily ice delivery. During the same week, the Greenwater Meat Company was organized and advertised that it would drive cattle across two mountain ranges from Owens Valley, California, to Greenwater, to furnish a constant supply of fresh meat daily to Greenwater inhabitants. The Furnace Townsite Company also stepped up its advertisements, and the Greenwater Townsite Company countered by running its own ads, plugging the unique and desirable aspects of its camp.

Still, qualms of uneasiness were beginning to be felt around the district. The Bullfrog Miner was the first local paper to admit such, noting that “As yet there are no real mines in Greenwater, as mining men understand the term.” The paper went on to qualify that statement, adding that the working shafts are down several hundred feet. The ore bodies are well enough defined so that the owners know that they have immense quantities of very valuable rock. Still, the workings so far have been confined to these shafts and no effort has yet been made to take out ore except such as was necessary for sinking the shafts.” Privately, many Bullfrog operators were glad to see that the Greenwater boom was abating, for, at the height of the rush, the drain of investment money towards Greenwater had decidedly hampered the operation of the mines around the Bullfrog District.

By the end of March, the Bullfrog Miner put the district’s population at 2,000, which indicated that it had not grown for the first month since the district had been discovered. However, both Greenwater and Furnace were described as being alive and bustling, and both townsites had hotels, lodging houses, saloons, feed corrals, freight companies, meat markets, auto lines, brokerage houses, attorneys, newspapers, boarding houses, etc. Three railroad lines had been surveyed into the district. The Ash Meadows water company was working on getting water piped into the district, and an electric light system was projected for the towns.

By the end of March, the Bullfrog Miner put the district’s population at 2,000, which indicated that it had not grown for the first month since the district had been discovered. However, both Greenwater and Furnace were described as being alive and bustling, and both townsites had hotels, lodging houses, saloons, feed corrals, freight companies, meat markets, auto lines, brokerage houses, attorneys, newspapers, boarding houses, etc. Three railroad lines had been surveyed into the district. The Ash Meadows water company was working on getting water piped into the district, and an electric light system was projected for the towns.

But, the boom had definitely slowed, as evidenced by the incorporation of far fewer companies. The Greenwater District’s exploration stage had finally drawn to a close, after a short but extremely violent boom, and the future of the district now depended upon what ore bodies were found under the ground during the subsequent development phase.

By the first of May, although 26 companies were still actively engaging in development work, it was becoming very apparent that unless someone found a large profitable copper lode soon, the district would be in trouble. The investing public, which by now expected great things from the district which had boomed so brilliantly, was becoming impatient, and as another month passed without any big ore strikes being made, stock prices began to slip.

The Death Valley Chuck-Walla noted the stock slump but blamed it on the eastern Wall Street stock manipulators. In reality, the Greenwater boom had led to too great expectations from the investing public, and suspicions of a gigantic fraud were now beginning to form among the ranks of far-off investors. Nor did it help the Greenwater District that the first effects of the Panic of 1907 were beginning to be felt on the eastern stock markets. Naturally, shares of mining companies that were still in the initial development stages were among the first to be unloaded by cash-hungry investors. Still, no one was ready to give up.

On June 1st, the Death Valley Chuck-Walla could still point to 25 companies at work, and although no sizeable ore bodies had yet been found, no one seemed quite willing to give up. Articles from the district’s two other papers, the Greenwater Times and the Greenwater Miner, also contained the same hopeful spirit. The Engineering & Mining Journal noted that 15 gas hoists were at work throughout the district more miners were at work than ever before. For once, the labor problem seemed to be solved, for the buying and selling of claims had ceased with the coming of harder times, and more and more miners were willing to give up their dreams of instant wealth and settle down to earning a steady wage.

Then, on June 22nd, the inevitable fire swept through part of Greenwater. Although the relative damage was rather light, considering the destructive potential for fires in mining camps built of canvas and wood, one saloon and the offices and presses of both the Greenwater Miner and the Death Valley Chuck-Walla were consumed. The eChuck-Walla editorshad only recently bought out the Greenwater Miner and tmmediately announced plans to secure new printing equipment and continue both publications. But, having financial difficulties after several weeks of trying to get their paper printed at the Bullfrog Miner office, the editors gave up and left the county.

The fire seemed to be an omen, for with the passing of the Death Valley Chuck-Walla, Greenwater’s loudest and brassiest booster, the fire seemed to go out of the district. The Ash Meadows Water Company, for example, had promised on June 29th that water would be connected into Greenwater by the 1st of August, but by July 13th, revised that date to September 15th, and added that pipe would be laid into Lee before Greenwater–indicating that the prospects of the Lee District now looked better to that company than did those at Greenwater.