~~

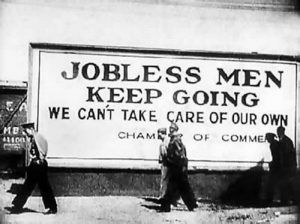

Seeking to halt the “invasion” of Dust Bowl Depression refugees in February, 1936, Los Angeles, California Police Chief James E. Davis declared a “Bum Blockade” to stop the mass emigration of poverty stricken families fleeing from the dust-torn states of the Midwest

In 1931, a severe drought hit the Southern and Midwestern plains. As crops died and winds picked up, dust storms began, literally blowing away the crops in “black blizzards” caused by years of poor farming practices and over-cultivation combined with the lack of rain. By 1934, 75% of the United States was severely affected by this terrible drought. The region most affected – the Great Plains, included more than 100 million acres, centered in Oklahoma, the Texas Panhandle, Kansas, and parts of Colorado and New Mexico. These millions of acres of farmland became useless and soon, hundreds of thousands of people were forced to leave their homes.

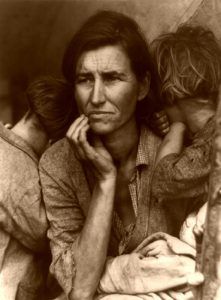

Many of these destitute families packed up their belongings and migrated west, hoping to find work and a better life, about 200,000 of which were California bound. Instead of finding the promised land of their dreams; however, they found that the available labor pool was vastly disproportionate to the number of job openings that could be filled.

Migrants who found employment soon learned that this surplus of workers caused a significant reduction in the going wage rate, and even when the entire family worked, they were unable to support themselves. Many set up “ditchbank” camps along irrigation canals in the farmers’ fields, which fostered poor sanitary conditions and created a public health problem. And, of those who could find work in agriculture, it did not put an end to their travels. Instead, their lives were characterized by transience if they wanted to maintain a steady income, which required them to follow the various harvests around the state.

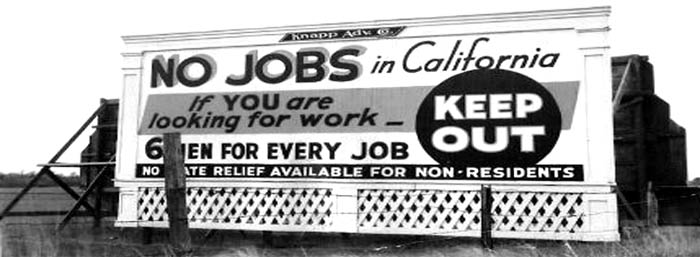

In the meantime, the Golden State was overwhelmed, trying to figure out how to absorb as many as 6,000 migrants crossing its borders daily. Also feeling the effects of the Depression, California infrastructures were already overburdened, and the steady stream of newly arriving migrants was more than the system could bear.

Though these refugees came from a number of states, Californians often lumped them together as “Okies” or “Arkies,” who became the butt of derogatory jokes and the focus of political campaigns in which candidates made them the scapegoat for a shattered economy. They were accused of many crimes, as well as shiftlessness, lack of ambition, school overcrowding and stealing jobs from native Californians.

Stay Away From California Warning To Transient Hordes

San Francisco, August 24 — Indigent transients heading for California today were warned by H. A. Carleton, director of the Federal Transient Service, “to stay away from California.”

Carleton declared they would be sent back to their home States on arrival here due to closing of transient relief shelters and barring of Works Progress Administration work relief in the State to all transients registered after August 1.

“California is carrying approximately 7 percent of the entire national relief load, one of the heaviest of any State in the Union,” said Carleton. “A large part of this load was occasioned by thousands of penniless families from other States who have literally overrun California.”

Carleton estimated the transient influx at 1,000 a day.

A program to construct camps for these many migrants streaming into California was begun and abandoned by the state government in 1935, but, was quickly taken over by the Resettlement Administration.

Even with the assistance of the Federal Government, Californians feared the additional expenses for welfare relief and public education. As a result, Los Angeles “declared war” on these many emigrants by implementing the “Bum Blockade” in February 1936. Usurping California’s state powers, Police Chief James E. “Two-Gun” Davis, with the support of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, many public officials, the railroads, and hard-pressed state relief agencies, dispatched 136 police officers to 16 major points of entry on the Arizona, Nevada, and Oregon, with orders to turn back migrants with “no visible means of support.”

Loosely interpreting California’s Indigent Act, passed in 1933, which made it a crime to bring indigent persons into the state, Davis contended that his men needed no special approval because “any officer has the authority to enforce the state law.”

Asking border-county sheriffs to deputize his officers, most complied. However, some refused, including Modoc County, who forced 14 LAPD officers to leave after they turned away local residents trying to return home.

Promising that $1.5 million would be saved on “thieves and thugs” and another $3 million in welfare payments, most newspapers of the time backed Davis and his blockade, including The Los Angeles Times, which compared Chief Davis to England’s 16th-century Queen Elizabeth, who “launched the first war on bums.” However, there was one newspaper – the now-defunct Los Angeles Evening News, which editorialized that the blockade “violates every principle that Americans hold dear … the right of any citizen to go wherever he pleased.”

Despite some protests, the officers turned back hundreds of railroad-fare evaders, hitchhikers, families in loaded down trucks and cars, and in the words of the Los Angeles Times, “all other persons who have no definite purpose in coming into the state.” The railroads obligingly halted freight trains near police outposts and the “captured” migrants were offered a choice of leaving California or serving a 180-day jail term with hard labor.

In answer to charges that the blockade was an outrage, the Los Angeles Times editorialized: “Let’s Have More Outrages” and continued to praise the effort as an answer to the waste of taxpayers’ “hard-got tax money” and a way to keep out “imported criminals … radicals and troublemakers.”

When California’s Deputy Attorney General, Jess Hession declared that Davis’ methods were illegal, he was overridden by the governor, Frank Merriam, who said it was “up to them [Los Angeles officials] if they can get away with it.”

After a couple of months, Davis’ blockade was finally withdrawn when the use of city funds for this project was questioned and a number of lawsuits were threatened. In early April, he called his officers home, but claimed his blockade a success, saying that the 11,000 people who had been turned away caused an “absence of a seasonal crime wave in Los Angeles.”

In 1937, the Resettlement Administration program was passed on to the newly created Farm Security Administration, who would build 13 migrant camps to temporarily house many of the indigents entering the state.

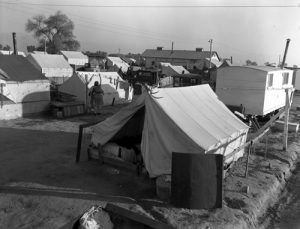

Each camp would temporarily house 300 families in tents built on wooden platforms. Designed to foster a sense of self-respect, the camps were self-governing communities, and families had to work for their room and board.

However, it wasn’t enough, and even when many of those, who arrived impoverished, could find jobs, their wages forced them to live in filth and squalor in tents and shanty towns, dubbed Hoovervilles because residents blamed President Herbert Hoover for their plight. These shantytowns sprouted up all over in areas such as the Arroyo Seco, San Gabriel Canyon and Terminal Island.

Though the “Bum Blockade” was over, border control efforts continued. In 1939, the district attorneys of several of the counties most affected by the Dust Bowl influx began using California’s Indigent Act of 1933, to stop the flow of the poor into their state. Enforcing the Indigent Act, which made it a crime to bring indigent persons into the state, they indicted, tried and convicted more than two dozen people who helped their relatives move into California from the Midwest.

However, the prosecutions were challenged by the American Civil Liberties Union, which pushed the issue all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, who issued a ruling in 1941 that states had no right to restrict interstate migration by poor people or any other Americans.

The Farm Security Administration continued the temporary housing program through World War II, when the problem was one of “mobilizing” sufficient farm labor. In 1942, the Farm Security Administration operated ninety-five camps with housing for seventy-five thousand people.

However, as the war went forward, the state of the economy, both in California and across the nation, improved dramatically as the defense industry geared up to meet the needs of the war effort. Many of the migrants went off to fight in the war. Those who were left behind took advantage of the job opportunities that had become available in West Coast shipyards and defense plants. As a result of this more stable lifestyle, numerous Dust Bowl refugees put down new roots in California soil, where their descendants reside to this day.

© Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated September 2021.