By Frederick Ritchie Bechdolt in 1922

Back in the wild old days, you found one on the new town’s outskirts and one where the cattle trail came down to the ford, and one was at the summit of the pass. There was another on the mesa overlooking the water-hole where the wagon outfits halted after the long dry drive. The cowboys read the faded writing on the wooden headboards and, from the stories, made long ballads which they sang to the herds on the bedding grounds. The herds have long since vanished, the cowboys have ridden away over the skyline, the sad songs are slipping from the memories of a few old men, and we go riding by the places where those headboards stood, oblivious.

Of the frontier cemeteries whose dead came to their ends, shod in accordance with the grim phrase of their times, there remains one just outside the town of Tombstone to the north. Here, straggling mesquite bushes grow on the summit of the ridge; cacti and ocotillo sprawl over the sun-baked earth hiding between their thorny stems the headboards and the long narrow heaps of stones which no man could mistake. Some of these headboards still bear traces of black-lettered epitaphs which tell how death came to strong men in the full flush of youth. But the vast majority of the boulder heaps are marked by cedar slabs whose penciled legends the elements have long since washed away.

The sun shines hot here on the summit of the ridge. Across the wide mesquite flat, the granite ramparts of the Dragoons frown all the long day, and the bleak hill graveyard frowns back at them. Thus the men who came to this last resting place frowned back at Death.

There was a day when every mining camp and cowtown from the Rio Grande to the Yellowstone River owned its boot hill; a day when lone graves marked the trails and solitary headboards rotted slowly in the unpeopled wilderness. Many of these isolated wooden monuments fell before the long assaults of the elements; the low mounds vanished and the grass billowed in the wind hiding the last vestiges of the leveled sepulchers. Sometimes the spot was favorable, outfits rested there, and new headboards rose about the first one. The road was long and weary; the fords were perilous from quicksands; thirst lurked in the desert, and the Indians were always waiting. The camp became a settlement, and in the days of its infancy, when there was no law save that of might, the graveyard spread over a larger area. There came an era when a member of that stern straight-shooting breed who blazed the trails for the coming of the statutes wielded the powers of high justice, the middle, and the low. Outlaw and rustler opposed the dominion of this peace officer. Then the cemetery boomed like the young town. Finally, things settled down to jury trials and men let lawyers do most of the fighting with forensics instead of forty-fives. Churches were built and school-houses; a new graveyard was established; brush and weeds hid the old one’s leaning headboards. Time passed; a city grew, and the boot hill was forgotten.

This is a chronicle of men whose bones lie in some of those vanished boot hills. If one could stand aside on the day of judgment and watch them pass when the brazen notes of the last trump are growing fainter, he would witness a brave procession. But we at least can marshal the shadowy host from fast-waning memories and, looking upon some of their number, recall the deeds they did, the manner of their death.

Here then they come through the curtain of time’s mists, Indian fighter, town marshal, faro-dealer, and cowboy. There are a few among them upon whom it is not worthwhile to gaze, those whose lives and deaths were unfit for recording; there is a vast multitude whose heroic stories were never told and never will be, and there are some whose deeds as they have come down from the lips of the old-timers should never die.

Thus in the forefront pass lean forms clad for the most part in garments fringed with buckskin. You can see where some have torn off portions of the fringes to clean their rifles.

Old-fashioned long-barreled muzzle-loaders, these rifles, and powder-horns hang by the sides of the bearers. They are long-haired men, and their faces are deeply burned by sun and wind, 183 of them, and where they died, fighting to the last against 4,000 of Santa Ana’s soldiers, rose the first boot hill. That was in San Antonio, Texas, at the Alamo. In this day, when schoolboys who can describe Thermopylae in detail know nothing of that far finer stand, it will do no harm to dwell on a proud episode ignored by many textbook histories.

On March 5, 1836, San Antonio’s streets were resonant with the heavy tread of marching troops, the clank of arms, and the rumble of moving artillery. Four thousand Mexican soldiers were being concentrated on one point, a little mission chapel, and two long adobe buildings which formed a portion of a walled enclosure, the Alamo.

For nearly two weeks, General Santa Ana had been tightening the cavalry, infantry, and artillery cordon about the place. It housed 183 lank-haired frontiersmen, a portion of General Sam Houston’s band who declared Texan independence. The Mexicans had cut them off from water; their food ran low. On this day, the dark-skinned commander planned to take the square. His men had managed to plant a cannon 200 yards away. When they blew down the walls, the infantry would charge. It only remained for them to load the field piece. Bugles sounded; officers galloped through the sheltered streets where the foot soldiers were held in waiting. There came from the direction of the Alamo the steady rat-tat-tat of rifles. The hours went by, but the cannon remained silent.

A little group of lean-faced men was crouching on the flat roof of the large out-building. Though most of them were clad in fringed buckskin garments, here and there was one in a hickory shirt and home-spun jeans. Six of them, some bareheaded and some with hats whose wide rims dropped low over their foreheads, were clustered about old Davy Crockett, frontiersman and a member of Congress in his day. Always the six were busy, with ramrods, powder-horns, and bullets, loading the long-barreled eight-square Kentucky rifles. The grizzled marksman took the cocked weapons from their hands; one after another, he pressed each walnut stock to his shoulder, lined the sights, pulled the trigger, and laid the discharged piece down, to pick up its successor.

He crouched there on the flat roof facing the Mexican cannon. As fast as men came to load it, he fired. Sometimes a dozen soldiers rushed upon the muzzle of the field-piece surrounding it. At such moments Davy Crockett’s arms swept back and forth with smooth, unhurried swiftness, and his sinewy fingers relaxed from one walnut stock only to clutch another; his hands were never empty. Always a little red flame licked the smoke fog before him like the tongue of an angered snake. He was getting on in years, but in all his full life, his technique had never been so perfect, his artistry of death so flawless, as on this day which prefaced the closing of his chapter. The bodies of his enemies clogged the space about their cannon; the rivulets of red trickled from the heap across the roadway. The long hours passed. Darkness came. The field-piece remained silent.

Long before daylight the next morning, the 4,000 were marching in close ranks to gather for the final assault. The sun had not risen when they made the charge. The infantry came first; the cavalry closed in behind them driving them on with bared sabers. The Americans took such toll with their long-barreled rifles from behind the barricaded doors and windows that the foot-soldiers turned to face the naked swords rather than endure that fire. The officers reformed them under cover; they swept forward again and again fell back. Santa Ana directed the third charge in person. They swarmed to the courtyard wall and raised ladders to its summit. The men behind bore those before them onward and literally shoved them up the ladders. They overwhelmed the frontiersmen through sheer force of numbers. Colonel W. B. Travis fell fighting hand to hand here. The courtyard was filled with dark-skinned soldiers.

The Alamo was fallen. But there remained for the lean hard-bitten men of Texas, who had retired within the adobe buildings, the task of dying as fighting men should die. It was now ten o’clock, nearly six hours since the beginning of the first advance. It took the four thousand two hours more to finish the thing. For every room saw its separate stand, and every stand was to the bitter end.

There were 14 gaunt frontiersmen in the hospital, so weak with wounds that they could not drag themselves from their tattered blankets. They fought with rifles and pistols until 40 Mexicans lay heaped dead about the doorway. The artillery brought up a field piece; they loaded it with grape-shot and swept the room, and then, at last, they crossed the threshold.

Colonel James Bowie, who brought the knife that bears his name, was sick within another apartment. One can well imagine how that day’s noises of combat roused the old fire within his breast and how he lay there chafing against the weakness which would not let him raise his body. A dozen Mexican officers rushed into the place, firing as they came. Colonel Bowie waited until the first of them was within arm’s length. Then he reached forth, seized the man by the hair, and, dying, plunged the knife that bore his name hilt-deep into the heart of his enemy.

So they passed in stifling clouds of powder smoke with the reek of hot blood in their nostrils. The noon hour saw Davy Crockett and five or six companions standing in the corner of the shattered walls; the old frontiersman held a rifle in one hand, in the other a dripping knife, and his buckskin garments were sodden, crimson. That is the last of the picture.

“Thermopylae had its messenger of defeat. The Alamo had none.” So reads the inscription on the monument erected in later years by the State of Texas to commemorate that stand. The words are true. But the Alamo did leave a memory, and the tale of the little band who fought in the sublimity of their fierceness while death was slowing their pulses did much toward the development of a breed whose eyes were narrow, sometimes slightly slanting, from constant peering across rifle sights under a glaring sun.

The procession is passing; trapper and Indian fighter; teamsters with dust in the deep lines of their faces — dust from the long dry trail to old Santa Fe; stage-drivers who have been sleeping the long sleep under waving wheat-fields where alkali flats once stretched away toward the vague blue mountains; and riders of the Pony Express. A tall form emerges from the past’s dim background and comes on among them.

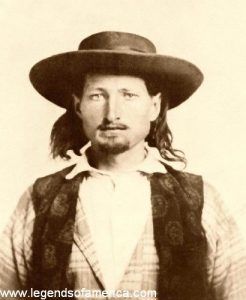

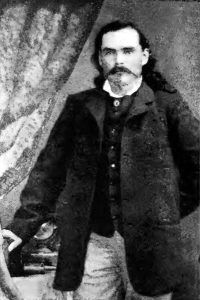

Six feet and an inch to spare, modeled as finely as an old Greek statue, with eyes of steel grey, sweeping mustache, and dark brown hair that hangs to his shoulders, he moves with catlike grace. Two forty-fives hang by his narrow hips; there is a hint of the cavalier in his dropping sombrero and his ornately patterned boots. This is Wild Bill Hickok; he was to have gone with Custer, but a coward’s bullet cheated him out of the chance to die fighting by the Little Big Horn, and they buried him in the Black Hills in the spring of 1876. James B. Hickok was the name by which men called him until one December day in the early sixties when the McCanles gang of outlaws tried to drive the horses off from the Rock Creek Station of the Overland Stage on the plains of southwestern Nebraska near the Kansas boundary.

There were ten of the desperadoes, and Hickok, who was scarcely more than a boy then, was alone in the little sod house, for Doc Brink, his partner, was off hunting that afternoon. He watched their approach from the lonely cubicle where he and Brink passed their days as station keepers. They rode up through the cottonwoods by the creek. David McCandless leaped from the saddle and swaggered to the corral bars.

“The first man lays a hand on those bars; I’ll shoot,” Hickok called. They answered his warning with a volley, and their leader laughed as he dragged the top railing from its place. Laughing he died.

Now the rifles of the others rained lead against the sod walls, and slugs buzzed like angry wasps through the window. He killed one more by the corral and a third who had crept up behind the wooden well-curb. The seven who were left retired to the cottonwoods to hold council. They determined to rush the building and batter down the door.

He got two more of them when they came back bearing a dead tree trunk between them. And then the timber crashed against the flimsy door; the rent boards flew across the room; the sod walls trembled to the shock. He dropped his rifle and drew his revolver as he leaped to meet them.

Jim McCanles and another pitched forward across the threshold with leveled shotguns at their shoulders. Young Hickok ducked under the muzzle of the nearest weapon, and its flame seared his long hair as he swung for the bearer’s mid-section with all the weight of his body behind the blow. Whirling with the swiftness of a fighting cat, he spurned the senseless outlaw with his boot and “threw down” on McCanles. Revolver and shotgun flamed in the same instant; McCanles fell dead; Hickok staggered back with eleven buckshot in his body. The other three were on him before he recovered his balance. He felt the searing of their bowie-knives against his ribs as they bore him down on the bed. Fingers closed in on his windpipe. He seized the arm in his two hands and twisted it as one would twist a stick until the bones snapped. He struggled to his feet, and the warm blood bathed his limbs as he hurled the two who were left across the room.

They came on crouching, and their knives gleamed through the thick smoke clouds. His bowie-knife was in his hand now, and he stabbed the foremost through the throat. The other fled. Hickok stumbled out through the door after him, and Doc Brink came riding back from his hunting expedition in time to lend his rifle to his partner, who insisted profanely that he was fit to finish what he had so well begun.

So young James Hickok shut his teeth against the weakness creeping over him and lined his sights on the last of his enemies; for the man whom he had felled with his fist and he with the broken arm had escaped sometime during the latter progress of the fight. That final shot was not so true as its predecessors; the outlaw did not die until several days later in Manhattan, Kansas.

When the eastbound stage pulled up that afternoon, the driver and passengers found the long-haired young station-keeper in a deep swoon, with 11 buckshot and 13 knife wounds in his body. They took him aboard and carried him to Manhattan, where he recovered six months later to find himself known as Wild Bill Hickok throughout the West.

How many men he killed is a mooted question. But it is universally acknowledged that he slew them all fairly. Owning that prestige whose possessor walks amid unseen dangers, he introduced the quick draw on his portion of frontier; and many who sought his life for the sake of the dark fame which the deed would bring them died with their weapons in their hands.

In Abilene, Kansas, where he was for several years town marshal, one of these caught him unawares as he was rounding a corner. Wild Bill complied with the order to throw up his hands and stood, rigid, expressionless, while the desperado, emulating the Plains Indians, tried to torture him by picturing the closeness of his end. He was in the midst of his description when Hickok’s eyes widened, and his voice was thick with seeming horror as he cried, “My God! Don’t kill him from behind!” The outlaw allowed his eyes to waver, and he fell with a bullet hole in his forehead.

As stage-driver, Indian fighter, and peace officer Wild Bill Hickok did a man’s work cleaning up the border. He was about to go and join the Custer expedition as a scout when one who thought the murder would give him renown shot him from behind as he was sitting in at a poker game in Deadwood, South Dakota. He died drawing his two guns, and the whole West mourned his passing. It had never known a braver spirit.

The silent ranks grow thicker: young men, sunburned and booted for the saddle; the restless souls who forsook tame Eastern farm-lands, lured by the West’s promise of adventure, and received the supreme fulfillment of that promise; the finest of the South’s manhood drawn toward the setting sun to seek new homes. They come from a hundred boot hills, from hundreds of solitary graves, from the banks of the Yellowstone, the Platte, the Arkansas, and the two forks of the Canadian Rivers.

There are so many who died exalted that the tongue would weary reciting the tales. This tattered group was with the 50 who drove off 1500 Cheyenne and Kiowa on Beecher Island. The Battle of the Arickaree was the name men gave the stand, and the sands of the north fork of the Republican River were red with the blood of the Indians slain by Forsythe and his half-hundred when night fell.

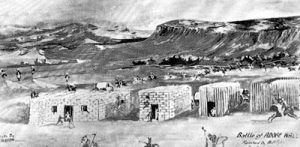

These three who follow in boots, jean breeches, and Oregon shirts are Billy Tyler and the Shadier brothers, members of that company of 28 buffalo hunters who made the big fight at Adobe Walls. The sun was just rising when Quanah Parker, Little Robe, and White Shield led more than eight hundred Comanche and Kiowa in the first charge upon the four buildings which stood at the edge of the Llano Estacado, 150 miles from the nearest settlement. The Shadier boys were slain in their wagon at that onslaught. Tyler was shot down at midday as he ventured forth from Myers & Leonard’s store. Before the afternoon was over, the Indians sickened of their losses and drew off beyond the range of the big-caliber Sharp’s rifles. They massacred 190 people during their three months’ raiding, but the handful behind the barricaded doors and windows was too much for them.

Private George W. Smith of the Sixth Cavalry is passing now. You would need to look a second time to notice that he was a soldier, for the rifle under his arm is a long-barreled Sharp’s single shot, and he has put aside much of the old blue uniform for the ordinary Western raiment. That was the way of scouting expeditions, and he, with his five companions, was on the road from McClellan’s Creek to Fort Supply when they met 200 Indians on that September morning of 1874.

Near the northeast corner of the Texas Panhandle, where the land rises to a divide between Gageby’s Creek and the Washita River, the five survivors dug his grave with butcher knives. They pulled down the banks of a buffalo wallow over his body in the darkness of the night, and they left him in this shallow grave, unmarked by stone or headboard. There, his bones lie to this day, and no man knows when he is passing over them.

The six of them had left General Miles’s command two days before. At dawn on September 13, they were riding northward up the long open slope: Billy Dixon and Amos Chapman, two buffalo hunters serving as scouts, and the four troopers, Sergeant Z. T. Woodhull, Privates Peter Rath, John Harrington, and George W. Smith. You could hardly tell the soldiers from the plainsmen had you seen them; a sombreroed group booted to the knees and in their shirt-sleeves; all bore the heavy, fifty-caliber Sharp’s single-shot rifles across their saddle-horns.

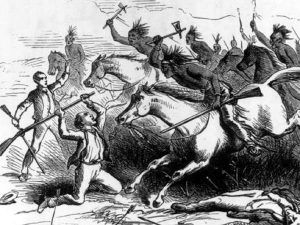

The bare land rolled away, dark velvet brown toward the flushing east. When they turned their horses up a little knoll, the sky was vivid crimson. They reached its summit just as the sun was rising. Here they drew rein. Two hundred Comanche and Kiowa were riding toward them at the bottom of the hill; the landscape had tricked them into an ambush.

There passed an instant during which astonishment held both parties motionless: the white men on the crest, unshaven, sunburned, their soiled sombreros drooping over their narrowed eyes, and at the slope’s foot, the ranks of half-naked braves all decked out in the warpath’s gaudy panoply. Their lean torsos gleamed under the rays of the rising sun like old copper; patches of ocher and vermilion stood out in vivid contrast against the dusky skins; feathered war-bonnets and dyed scalp locks fluttered, gay bits of color in the morning breeze. The instant passed; the white men flung themselves from their saddles; the red men deployed, forming a wide circle about them. An ululating yell, so fierce in its exultation that the cavalry horses pulled back upon their harnesses in a frenzy of fear, broke the silence. Then the booming of the long Sharp’s fifties on the summit mingled with the rattle of Springfields and needle-guns on the hill’s flank.

Now, while the bullets threw the dust from the dry sod into their faces, five of the six dropped on their bellies in a ring. And by the sergeant’s orders, Private George Smith took charge of the panic-stricken horses. Perhaps that task fell to him because he was the poorest shot; perhaps it was because he had the least experience, but it was a man’s job. He stood upright clinging to the tie-ropes, trying to soothe the plunging animals, and he became the target for a hundred of those rifles which were clattering along the hillside below him. For every warrior in the band knew that the first bullet that found its mark in his body would send the horses stampeding down the slope, and to put his foes afoot was the initial purpose of the plains Indian when he went into battle.

So Private Smith clenched his teeth and did his best while the deep-toned buffalo guns roared, and the rifles of the Indians answered in a never-ending volley all around him. The leaden slugs droned past his ears as thick as swarming bees; the plunging hoofs showed through the brown dust clouds, and his arms ached from the strain of the tie-ropes.

Billy Dixon had thrown away his wide-rimmed sombrero, and his long hair rippled in the wind. He had been through the battle at Adobe Walls, and men knew him for one of the best shots in the country south of the Arkansas River. He was taking it slowly, lining his sights with the coolness of an old hand on a target range. Now he raised his head.

“Here they come,” he shouted.

The circle drew inward where the land sloped up at the easiest angle. A hundred half-naked riders swung toward the summit, and the thud-thud of the ponies’ little hoofs was audible through the rattle of the rifles. The buffalo guns boomed in slow succession like the strokes of a tolling bell. Empty saddles began to show in the forefront. The charge swerved off, and as it passed at point-blank range, a curtain of powder smoke unrolled along the whole flank.

Private George Smith pitched forward on his face. His rifle flew far from him. He lay there motionless. A trooper binding his wounded thigh glanced around when the assault had become a swift retreat.

”Look!” he cried. “They’ve got Smith.”

”Set us afoot,” another growled and pointed after the stampeded horses.

Smith lay quite still as he had fallen. They thought him dead. A dozen whooping Comanche ran their ponies up the hill toward his limp form within the hour. To gain that scalp-lock under fire would be an exploit worth telling to their grandchildren in after years. And there was the long-barreled rifle as a bit of plunder. But the five white men, who had changed their position under a second charge, emptied four saddles before the warriors were within a hundred yards of the spot, and the eight survivors whipped their ponies down the slope again.

The sun was climbing high when Amos Chapman rolled over on his side and told Billy Dixon that his leg was broken. Dixon lifted his head and surveyed the situation. The Indians were gathering for another rush. Thus far, they had taken things as though they were so sure of the ultimate result that they did not see fit to run great chances. But this could not last. The next charge might be the final one. He saw a buffalo wallow on a little mesquite flat about 200 yards distant. He pointed to it.

“We got to make it,” he told the others, and they followed him as he ran for the shelter. But Amos Chapman crawled only a dozen paces or so before he had to give it up. The four fell to work with their butcher knives heaping up the sand at the summit of the low bank which surrounded the shallow circular depression. They dropped their knives and picked up their rifles, for the Indians were sweeping down upon them.

So they dug and fought and fought and dug for another hour, and then Billy Dixon was unable to stand the sight of his partner lying helpless on the summit of the knoll.

“I’m going to get Amos,” he announced and set forth amid a rain of bullets. Those who saw him after the fight—and General Miles was among them —said that his shirt was ripped in twenty places by flying lead. He halted on the hilltop and took up Chapman pick-a-back, then bore him slowly down the slope to the little shelter.

Noon came on. The sun shone hot. Dixon had got a bullet in the calf of his leg when he was bearing his companion on his back. Private Rath was the only man who was not wounded. They all thirsted as only men can thirst who have been keyed up to the high pitch of endeavor for hours. The Indians charged thrice more, and when they came, numbers of them always deployed toward the top of the knoll where Private Smith lay dying: dead, his companions thought, but they were grim in their determination that the red men should never get the scalp which they coveted so sorely. The big Sharps boomed; the saddles emptied to their booming. Private Smith wakened from one swoon only to fall into another. Sometimes he awakened to the thudding of hoofs and saw the Indians sweeping toward him on their ponies.

Near mid-afternoon, the warriors formed for a charge, and it was evident from the manner of their massing that they were going to ride down on the buffalo wallow in one solid body. But while their ranks were gathering, there came up one of those sudden thunderstorms for which the Staked Plains were famous. The rain fell in sheets; the lightning blazed with scarcely an intermission between flashes. And the charge was given up for the time being. The braves drew off beyond rifle shot and huddled up within their blankets. Morris Rath seized the respite to go for ammunition. For Smith’s cartridge belts were full. He came back from the knoll breathless.

“Smith’s living,” he cried.

“Come on,” Billy Dixon bade him, and the two went back to the summit.

“I can walk if you two hold me up,” Private George Smith whispered. A bullet had passed through his lungs, and when he breathed, the air whistled from a hole beneath his shoulder blade. They supported him on either side and half-carried him to the buffalo wallow.

The thunder-shower had passed. Another was coming fast. The Indians were gathering to take advantage of the brief interval. The agony that had come from rough motion kept Smith from swooning now. He saw his companions preparing to stand off the assault. Amos Chapman was holding himself upright by bracing his body against the side of the wallow. Private Smith whispered to the others,

“Set me up like Chapman. They’ll think there’s more of us fit to shoot that way.” And they did as he had asked them.

So he held his body erect while the life was ebbing from it, and the rain came down again in sheets. The Indians fell back before the charge was well begun. It was their last attempt.

The wind rose, biting raw. The Indians melted away as dusk drew down over the brown land. Someone looked at Smith. His head was sunk, and he was moaning with pain. They found a willow switch and tamped a handkerchief into the wound. And then they laid him down in the rainwater which had gathered in the wallow. His blood and the blood of the others turned that water a dull red.

Sometime near midnight, he died. And several days later, when General Miles’s troops came to rescue them, the five others buried his body. It was nighttime. The fires of the troopers glowed down at the foot of the slope. They made the grave with their butcher knives by pulling the sand from the wallow’s side upon the body. And then they went to the campfires of the soldiers.

They are passing from bleak graveyards on the alkali flats and in the northern mountains where the sage-brush meets the pines: gaunt men in laced boots and faded blue overalls who traveled once too often through the desert’s mirage searching for the golden ledges; big-boned hard rock men who died in underground passages where the steel was battering the living granite; men with soft hands and cold eyes who fattened on the fruits of robbery and murder.

This swarthy black-haired one in the soft silk shirt and spotless raiment of the gambler is Cherokee Bob, who killed and plundered unchallenged throughout eastern Washington and Idaho during the early 1860s; until the camp of Florence, Idaho celebrated its third New Year’s Eve with a ball in which respectability held sway, and he took his consort there to mingle with the wives of others. Then he kindled a flame of resentment which his blackest murders had failed to rouse. The next morning the entire camp turned out to drive him away together with Bill Willoughby, his partner. The two retreated slowly, from building to building, facing the mob. Shotguns bellowed; rifle-bullets sang about their ears, and they answered with their revolvers until death left their trigger fingers limp.