In 1927, America was shocked and horrified by the deaths and injuries of dozens of children and adults in the Bath School disaster. Also known as the Bath School Massacre, as of today, it remains the deadliest attack on a school in U.S. History.

About ten miles northeast of Lansing, Bath Township, which contains the unincorporated village of Bath, was your typical Michigan agriculture community in the early 1920s. Until then, there were many one-room schools with students in various grades sharing the same teacher, but in 1922, the Township voted to create a consolidated school district, building a new school funded by increased property taxes. When the Bath Consolidated School opened that November, there were 236 students. The endeavor was expensive in terms of a small community. The district purchased five acres for an athletic field in 1923, bought and paid for two lighting plants, and paid interest on eight thousand dollars on the principal, leaving the township bonded for $35,000 on the school. Resident’s school taxes started at $12.26 per thousand valuation but had gone up to $19.80 per thousand by 1926.

The Murderer

Andrew Kehoe, the perpetrator of the Bath School disaster circa 1920, reprinted in M.J. Ellsworth, The Bath School Disaster (1928).

Described as the “world’s worst demon,” Andrew P. Kehoe was born on a farm in Michigan near Tecumseh in 1872. Studying electrical engineering at Michigan State College in East Lansing, Kehoe set off on his new career in St. Louis, Missouri. However, he returned to his father’s farm after a few years. In September 1911, his stepmother was killed in an oil stove explosion. Kehoe had tried to extinguish the flames on her with a bucket of water, which only spread the flames more rapidly over her body. Some neighbors at the time believed he had caused the explosion.

In 1912 he married Nellie Price, whom he had met while in college. Early on, there were examples of Kehoe’s ‘disgust’ at paying for something through taxes or assessments. After a new one was built, he removed himself and his wife from a Roman Catholic Church and was assessed $400. When the priest asked why he no longer came to church or made an effort to pay the assessment, Kehoe ordered him off his property.

In 1919 the couple moved to the farm outside of Bath, with 185 acres. At first, he was social, doing favors and volunteer work for his neighbors, but many described him as always wanting his way and having nothing to do with others who disagreed. Some added that he was “severe” with his stock, especially horses. He didn’t farm like his neighbors, always trying new methods and tinkering so much with the tractor that he wasn’t very prosperous. Other troublesome behavior included shooting his neighbor’s dog because it was a “damn nuisance,” although the dog had never come onto Kehoe’s property.

In 1923, Kehoe was enraged over a raise in taxes for the consolidated school, which resulted in a $10,000 tax bill on his remaining 80 acres of land and buildings. That’s when he found his way onto the school board in July of 1924 and was appointed treasurer. Being insistent on getting his way, he often clashed with other board members and would make a motion to adjourn if they disagreed with him. He had a special disgust at the School Superintendent, Mr. E.E. Huyck, who at one time Kehoe told him he would have to leave the board meetings as he had no business to sit with them. It took some convincing from the others that Huyck was required to be there.

In 1925 Kehoe was appointed township clerk to fill the vacancy left by the death of the previous clerk. He ran for the position in the 1926 election but was defeated due to his reputation on the school board. Around this time, he tried to convince the township to cut the valuation on his farm and even convince the mortgage holder he had paid too much, but no one would agree.

During the school summer vacation in 1926, Kehoe volunteered to do electrical and repair work at the school, giving him free access to the entire building. It’s thought, by at least one resident, this was when his plan to exact vengeance on the community was set in motion. On May 5, 1927, Kehoe attended his last board meeting, seemingly amicable toward all the board’s business, smiling with approval throughout.

One witness, Monty J. Ellsworth, a neighbor, and friend of Kehoe, would later write that on Monday, May 16, two days before the attack, fifth-grade teacher Blanche Harte contacted Kehoe about having a school picnic on his property that Thursday. After agreeing, Kehoe called her back, asking her to move it up to Tuesday, saying it may rain on Thursday. Ellsworth wrote, “I suppose he wanted the children to have a little fun before he killed them.”

The Massacre

On the morning of May 18, 1927, Andrew Kehoe began his attack on his own farm. He began by putting all the railings and lumber around his buildings into his tool shed. He had cut the wire fences on the farm and put dynamite on his tractor in the shed. The only animals left on the farm, two horses, were tied in the barn, feet bound by wire so that rescuing them would be impossible. At some point, he killed his wife Ellen (also known as “Nellie”), who was chronically ill with what is thought to have been tuberculosis. Her medical bills may have been why he had ceased making mortgage and homeowner insurance payments months earlier. She was released from the hospital that Monday, so it is unclear when he killed her.

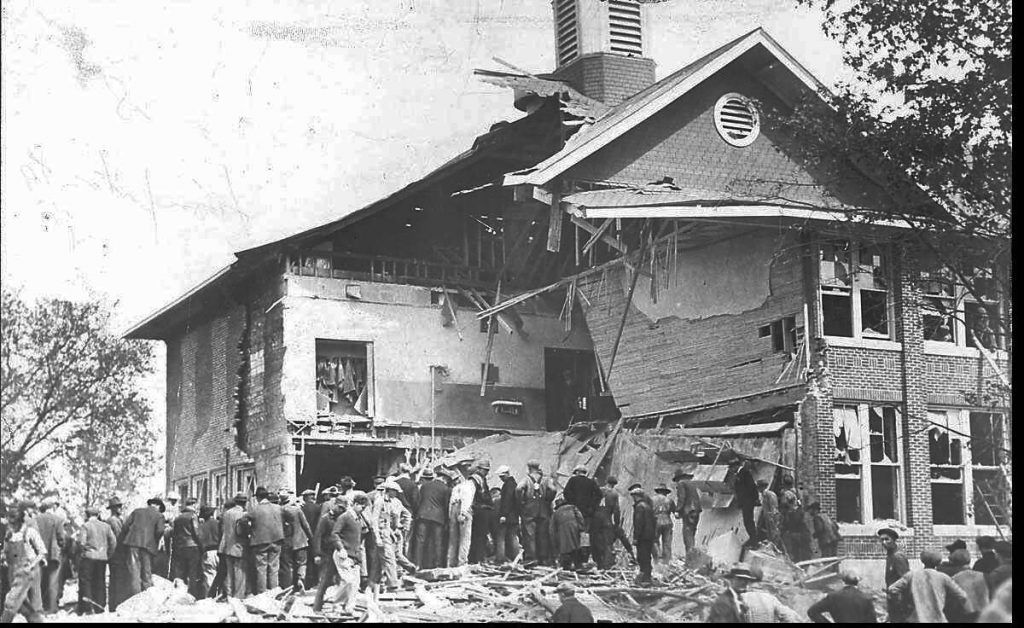

Around 8:45 a.m., witnesses saw the Kehoe farm go up in flames. Neighbors began to rush to his farm when the north wing of the school exploded about the same time. Kehoe had hidden an alarm clock that detonated the dynamite and pyrotol. 38, mostly children, died in the initial blast. First-grade teacher Benice Sterling, in an interview with the Associated Press, said

“It seemed as though the floor went up several feet. After the first shock, I thought for a moment I was blind. When it came, the air seemed to be full of children and flying desks and books. Children were tossed high in the air; some were catapulted out of the building.”

Residents pitch in to find survivors after school board member Andrew Kehoe dynamited the Bath Michigan Consolidated School on May 18, 1927. A.P. Photo (Detroit News)

According to accounts from “The Bath School Disaster,” a book by Ellsworth, two neighbors arrived at the farm as Kehoe was pulling out with his Ford pickup. Kehoe told them, “You are friends of mine, don’t go in there; go down to the school.” Then he leisurely drove toward Bath. He passed Ellsworth, who was on his way back to his farm to get a heavy rope to pull out victims of the blast. Ellsworth said as they met on the road; Kehoe grinned and waved. Ellsworth surmises that Kehoe was disappointed when he got to the school about half an hour later and saw that not all the planted dynamite had exploded.

It was complete chaos as parents and volunteers rushed to assist. Kehoe pulled up, motioned Superintendent Huyck over, and detonated dynamite in his pickup shortly after killing himself, the Superintendent, and three others, including an 8-year-old boy who had survived the first blast.

Hundreds of people worked through the wreckage into the night to find survivors. When they discovered an additional 500 pounds of dynamite in the south wing, the search was halted so that Michigan State Police could disarm them. Another alarm clock was found with the same “8:45 a.m.” setting, but investigators say the north wing blast must have caused a short circuit in the second set of bombs, preventing their detonation.

The attack had taken the lives of 44 and injured another 58. Despite competing with Charles Lindbergh’s historic transatlantic crossing, national coverage brought a worldwide outpouring of grief in the following days. It was reported that over 100,000 vehicles passed through that Saturday, with burials beginning that Friday.

Andrew Kehoe was buried in an unmarked grave in the poor section of Mount Rest Cemetery in St. Johns, Michigan. His wife Nellie was buried in Lansing’s Mount Hope Cemetery under her maiden name.

The Victims

Nellie Kehoe – 52

Arnold V. Bauerle, age 8, 3rd grade

Henry Bergan, age 14, 6th grade

Herman Bergan, age 11, 4th grade

Emilie M. Bromundt, age 11, 5th grade

Robert F. Bromundt, age 12, 5th grade

Floyd E. Burnett, age 12, 6th grade

Russell J. Chapman, age 8, 4th grade

F. Robert Cochran, age 8, 3rd grade

Ralph A. Cushman, age 7, 3rd grade

Earl E. Ewing, age 11, 6th grade

Katherine O. Foote, age 10, 6th grade

Marjorie Fritz, age 9, 4th grade

Carlyle W. Geisenhaver, age 9, 4th grade

George P. Hall, Jr., age 8, 3rd grade

Willa M. Hall, age 11, 5th grade

Iola I. Hart, age 12, 6th grade

Percy E. Hart, age 11, 3rd grade

Vivian O. Hart, age 8, 3rd grade

Blanche E. Harte, age 30, teacher

Gailand L. Harte, age 12, 6th grade

LaVere R. Harte, age 9, 4th grade

Stanley H. Harte, age 12, 6th grade

Francis O. Hoeppner, age 13, 6th grade

Cecial L. Hunter, age 13, 6th grade

Doris E. Johns, age 8, 3rd grade

Thelma I. MacDonald, age 8, 3rd grade

Clarence W. McFarren, age 13, 6th grade

J. Emerson Medcoff, age 8, 4th grade

Emma A. Nickols, age 13, 6th grade

Richard D. Richardson, age 12, 6th grade

Elsie M. Robb, age 12, 6th grade

Pauline M. Shirts, age 10, 5th grade

Hazel I. Weatherby, age 21, teacher

Elizabeth J. Witchell, age 10, 5th grade

Lucile J. Witchell, age 9, 5th grade

Harold L. Woodman, age 8, 3rd grade

George O. Zimmerman, age 10, 3rd grade

Lloyd Zimmerman, age 12, 5th grade

Killed by the truck bombing

G. Cleo Clayton, age 8, 2nd grade

Emory E. Huyck, age 33, superintendent

Andrew P. Kehoe, age 55, perpetrator

Nelson McFarren, age 74, retired farmer

Glenn O. Smith, age 33, postmaster

Died later of injuries

Beatrice P. Gibbs, age 10, 4th grade

©Dave Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2023.

Also See:

Michigan – The Great Lakes State

Sources:

“The Bath School Disaster“, Monty J. Ellsworth, 1928

Wikipedia