Ruby, Arizona, is one of the best-preserved ghost towns in the state, filled with history, including lawlessness, murder, and mayhem, not to mention dozens of great photographic opportunities.

In 2007, on our roundabout journey from Phoenix to Nogales, we took the road less traveled, exiting off of I-19 and eventually onto a dirt road adventure. Nestled below Montana Peak, rich minerals were discovered here by the Spaniards who came through in the 1700s. However, they were not rich enough for their tastes, so they performed only limited placer mining before moving on. The area remained undisturbed for nearly a century until two mining engineers, Charles Poston and Henry Ehrenberg, revived the old Spanish placers in Montana Gulch in 1854. Other prospectors followed, discovering rich veins of gold and silver, but mining remained limited primarily due to the hostile Apache inhabiting the area.

However, by the 1870s, new prospectors made several additional claims, and the fledgling settlement formed at the mountain base was called “Montana Camp.” Lead, copper, and zinc veins were also found in the immediate vicinity, beckoning more miners to the fledgling settlement.

The Ruby Mercantile was first opened in the late 1880s by George Cheney. In 1891, a large body of high-grade ore was discovered in the “Montana Mine” by J. W. Bogan and company, who pronounced the Montana Mine a veritable “bonanza.” Prospectors began to flood the region when samples were assayed at eighty to ninety ounces of silver per ton.

In 1897, the Ruby Mercantile was purchased by Julias Andrews. More than a decade later, Andrews applied for a post office, which opened in the store in April 1912. He named the post office, and effectively, the town — Ruby, for his wife, Lillie B. Ruby Andrews.

During Ruby’s early days, camp life was unglamorous, and most miners lived in tents or adobe huts. There were no businesses other than the general store, which was the only lifeline for the miners. Most men relied on hunting to provide food for their families, but others would turn to cattle rustling.

In 1914, Andrews sold the store to Philip C. Clarke, who built a bigger and better one just up the hill, the remains of which still stand today.

Like most other early mining camps, Ruby had its share of lawlessness. However, for this camp, so near the Mexican border, attacks by the town’s hostile neighbors were widespread, so much so that store owner Philip Clarke and his wife, Gypsy, kept weapons in every room of their house and store. Mr. Clarke felt that the town was so dangerous he insisted that his wife travel to California to give birth to their son, Dan.

In the beginning, Ruby grew slowly due to its dangerous location and high cost of ore processing, hampered by poor extraction methods and inadequate water. A dam was built to collect water runoff, and several small operators worked the ore, but it would be more than a decade before the rich minerals were worked in large quantities.

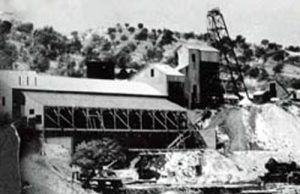

In 1915, the Montana Mine was leased by the Goldfield Consolidated Mines Company, which began the first large-scale operation. Soon, the Montana Mine grew to be a leading producer of lead.

Though Ruby was growing, it was still a lawless place, and finally, Philip Clarke became so concerned for his family’s safety that he moved them away to nearby Oro Blanco. However, he continued to work at the Ruby Mercantile and amassed large amounts of land and cattle until 1920, when he sold the store to brothers John and Alexander Fraser.

Clarke warned them of the Mexican bandits that were prone to terrorizing the area, telling them always to be well-armed. But, for the Fraser brothers, the warning was not enough. Less than two months later, on February 27, 1920, they were found shot in the store. Authorities were immediately called, and when they arrived, they found Alexander Frazer lying dead near the cash register, with a bullet in his back and another in his head. Amazingly, his brother John was still alive with a shot through his left eye. However, he would die five hours later without ever regaining consciousness.

The Nogales’ Weekly Oasis stated in part,

“…tragedy is nothing new over there. In the wild and rugged region south from the Atascosa Mountains and the Bear Valley region, there has always been a harbor for a bunch of desperate characters, whose depredations have been felt by American cattlemen and ranchers through many years.”

Upon investigating, the authorities found that the telephone, the only one in Ruby, had been torn off the wall and its wires cut. The store and its post office had been robbed. Upon questioning neighbors, it was found that two unknown Mexicans had been seen in the area, and two sets of footprints were found in the dust around the mercantile. That same night, a prominent rancher in the area reported that two of his best saddle horses and eight head of cattle had been stolen. Believing that the two incidents might be connected, lawmen followed the cattle trail, searching in vain for the rustlers. Several suspects were rounded up in the following months, but no charges were made.

One investigator was told by an old-time local that there was a curse on the building. Explaining further, the local said: “Old Tio Pedro died years ago. He predicted evil for the occupants of the post office ’cause it was built over an old padre’s grave.” The investigator confirmed the superstition with the local peace officer, who informed the investigator that the legend was common among the Mexicans in the area.

Perhaps there was something to the superstition, as murder and mayhem were not yet over at the Ruby Mercantile.

The Fraser heirs were approached by Frank Pearson shortly after, who was interested in buying the Ruby Mercantile. Though Pearson was vehemently warned of the potential danger, he brushed aside the advice, insisting that another attack was unlikely. The deal was closed, and Pearson, his wife, Myrtle, and four-year-old daughter, Margaret, moved in and reopened the store. Less than a year later, Mr. and Mrs. Pearson would also die.

By this time, the town of Ruby was virtually deserted, other than the mercantile and post office. Their closest neighbor was eight miles away. They soon sent for Myrtle’s younger sister, Elizabeth Purcell, and her husband’s sister, Irene, to keep them company and help with the store.

On the morning of August 26, 1921, Mr. and Mrs. Pearson took a horseback ride in the surrounding hills, leaving their young daughter, Margaret, in the capable hands of their sisters. While they were away, they spied several vaqueros galloping toward Ruby, and believing they might be needed at the store, they quickly returned.

When the seven Mexican cowboys strode into the store, they immediately demanded tobacco. But as Pearson turned to get it, shots roared from behind him. Grabbing his gun from under the counter, he fired three wild shots at the bandits, but he was mortally injured and fell to the floor dead.

Screaming, Irene Pearson ran to the rear of the building as one of the desperadoes pursued her, waving his pistol wildly. When she stumbled, the vaquero grabbed her by the hair and dragged her across the room. When Myrtle also began to scream, running toward Irene, the bandit threw Irene aside. Having spied five gold-crowned teeth in Myrtle’s open screaming mouth, he brought his gun down hard on her head. He then shot her in the neck, pried open her mouth, and knocked out the gold crowns with the butt of his gun.

While this terrible mutilation occurred, little four-year-old Margaret appeared in the doorway, her eyes wide with terror. Irene grabbed her, and the two hid under a couch. In the meantime, Elizabeth crawled behind the counter, where she grabbed Pearson’s shotgun, but one of the bandits was quicker. Another shot rang out, and Elizabeth slumped behind the counter.

Amazingly, Myrtle was still alive on the floor. Noticing her twitching body, another bullet was soon sent into her mutilated form, and she was dead.

Ignoring the three young girls, the bandits shot open the safe, pocketing anything of value before helping themselves to items they wanted from the store. They then tore the phone from the wall as they left on fast horses, screaming like banshees and shooting their pistols in the air.

Irene and Margaret warily crawled from the hiding place and revived Elizabeth, who had fainted and, luckily, had suffered no more than a graze to the arm by the bullet sent in her direction. Traumatized, they eventually made their way to the nearest neighbor eight miles away.

By the time authorities arrived at the scene, it was evening. They found Pearson behind the counter with two bullets in his back. His wife had a fractured skull, a shot through her neck, a bullet hole through her head, a broken jaw, and missing teeth. Even the crime-hardened authorities were appalled by the brutality.

Immediately, they suspected that those very same bandits had killed the Fraser brothers. Pearson was shot in the back just like Alexander Fraser; the safe had been robbed once again, and the telephone torn from the wall as before. The girls’ descriptions of two killers matched those reported a year earlier when the Frasers were killed.

The news of the brutal murders spread rapidly, and ranchers joined a posse to search for the killers. In the meantime, the superstitious Mexican locals crossed themselves as they spoke in hushed whispers about the old Tio Pedro legend. As the lawmen combed the desert hills, an airplane was chartered from the army post at Nogales to fly over the area in a more comprehensive hunt for the vicious criminals. It was the first airplane ever used in Arizona for a manhunt.

A $5,000 dead or alive reward was soon posted for each of the seven outlaws. Mexican authorities agreed to cooperate with the Arizona lawmen in the capture of the vaqueros. During the following months, reports showed that two Mexican men, drinking in a Senora saloon, had boasted of robbing the Ruby post office. Though Arizona authorities followed up, they still could not find the men.

By April 1922, they had almost given up when an Arizona deputy was in a Sasabe, Sonora cantina some thirty-five miles southwest of Ruby. Standing at the bar, he overheard the bartender trying to sell something to a customer. As he glanced over, he saw five gold teeth in the bartender’s hand. Immediately questioning him, he found that the bartender had bought them from another customer named Manuel Martinez. Sure, they were those of Myrtle Pearson, the deputy bought the teeth and returned them to the Arizona authorities. Familiar with Martinez, the officials knew he was often in the company of one Placido Silvas, who lived in a shack in the Oro Blanco district. Silvas was soon questioned and identified by witnesses as one of the vaqueros who had been at the Ruby Store the day of the brutal killings. He was quickly charged with the murder of Frank Pearson. On May 10, 1922, Placido Silvas went on trial for his life.

In the meantime, a search for Manuel Martinez was underway. Before long, he was tracked down in the mountains, who threatened to lynch him as a ploy to get him to confess. In no time, Martinez spilled his guts. He was brought in just as the jury was out on Silvas’ verdict. Martinez was immediately booked for murder, and Silvas’ jury was dismissed, pending further evidence from Martinez.

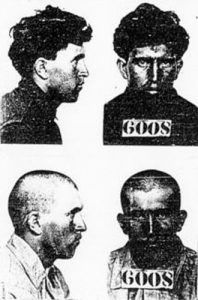

Despite his confession, Martinez pleaded not guilty in the Santa Cruz County Superior Court on May 16, 1922. However, two days later, it took 12 jurors only 40 minutes to find him guilty of first-degree murder.

The very next day, Silvas’ trial began once again in earnest. The jury was hung despite the evidence, and a new trial was ordered.

A third trial was ordered for Silvas, which lasted 21 days, going on record as the longest criminal trial ever held in Santa Cruz County. After hours of debate, the jury finally found Silvas guilty of murder.

On July 12, the two men appeared for sentencing. Martinez was sentenced to be hanged on August 18, 1922, while Silvas was sentenced to life imprisonment in the Arizona State Penitentiary. Judge W.A. O’Connor said of the crime: “The crimes of which you have been convicted are perhaps the cruelest ever committed in Arizona. Let the punishment that awaits you serve as a warning to others who may contemplate the commission of similar crimes.”

But the drama was not yet over. The next night, Santa Cruz County Sheriff George White and Deputy L. A. Smith loaded the prisoners into a car to take them to the state prison at Florence. But, before they reached their destination, Pima County Sheriff Ben Daniels received a disturbing phone call. The prisoner’s car had been found rolled over in a ditch near Continental, Arizona. Near the car, the bodies of White and Smith were sprawled on the ground with their skulls caved in. White was already dead, but Smith was still breathing and was rushed to the hospital.

Authorities immediately began an investigation, finding a place about 200 feet from the wreck where it appeared the prisoners had jumped from the moving car. Nearby was a blood-stained wrench used to bludgeon Officers White and Smith.

Lawmen, using dogs, immediately began to pursue the outlaws. But it was raining, and the dogs quickly lost the scent. The pursuit was given up for the night but immediately resumed the following day. Following their trail over the Santa Rita Mountains, they lost it near Ruby.

In the meantime, Deputy Smith died without ever regaining consciousness. As the news spread of a third double murder, area citizens were enraged, and volunteer posses poured in from Pinal, Pima, Cochise, and Santa Cruz counties, who were sent out to scout the desert and guard the roads.

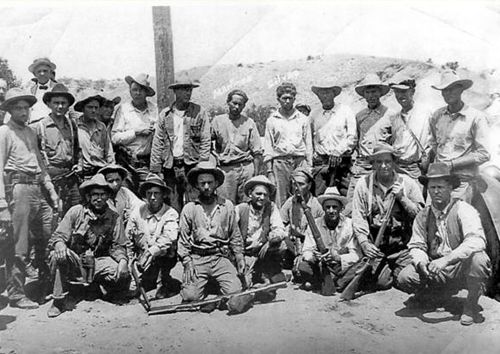

Posse and Prisoners. Over 200 men pursued Pearson’s murderers after they escaped during transport to the prison in Florence. Silvas and Martinez are in the middle of the back row. Photo courtesy Nogales Herald, July 20, 1922.

The dogs were brought in once again but were of no help. Five days after the convicts’ escape, some 700 men were combing the area in the most extensive manhunt in the history of the entire Southwest.

Finally, on the sixth day, a blood-stained file was found that authorities believed the convicts had used to cut off their handcuffs. Immediately, the lawmen were on the trail again, finally catching up with the pair hiding underbrush in the Tumacacori Mountains. Having run over 70 miles of broken country, they raved with thirst and exhaustion. Arrested again, they were taken to Nogales before being whisked off again to the penitentiary. This time, there would be no escape for the two men.

On his execution date, Martinez was granted a last-minute stay of execution. As his appeals dragged on, they were finally exhausted, and he was sentenced to die again on May 23, 1923.

In another desperate attempt, the Mexican Consul obtained a writ that again delayed Martinez’s execution. However, the Supreme Court intervened, quashed the writ, and sentenced the killer to die for the last time. On August 10, 1923, Martinez was hanged.

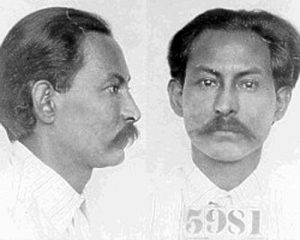

Placido Silvas escaped from prison and was never seen again. Photo courtesy Arizona Department of Corrections.

Placido Silvas was sent to prison for life. However, on December 3, 1928, he escaped from a State Penitentiary work ranch and was never seen again.

In the meantime, the town of Ruby, so drenched in blood, petitioned the U.S. War Department for protection, which stamped out the threat of bandit raids. Ruby lived on, albeit quietly, for the next couple of years. Unbelievably, the store sold again and was run by a man named Worthington, who operated it for a couple of years.

In 1926, Ruby was to see excitement again when the Eagle-Picher Lead Company bought the mine. Leading to Ruby’s most prosperous period, the Eagle-Picher Lead Company brought in much-improved technology, hired 300 men, built several dams to obtain water, and the town boomed.

When the dams still did not provide enough water, the company built a 15-mile-long pipe extending to the Santa Cruz Valley that lifted water 1,500 feet in two storage tanks. Before long, the town had electricity provided by the company’s diesel engines, a doctor, an infirmary, company stores, a school with three teachers instructing eight grades, the ever-present saloon, and some 2,000 residents. The mine ran 24 hours daily, only closing on Christmas and July 4.

From 1934 to 1937, the Montana Mine was the leading producer of lead and zinc in the state and the third-largest in silver production. However, the ore finally played out in 1940, and the town became a ghost. The mill operation was moved to Sahuarita. The post office closed forever on May 31, 1941. Though no records exist on the dollar amount taken from the Montana Mine, one estimate puts the total for the Oro Blanco district at more than $10 million between 1909 and 1949.

The Ruby Mercantile remained intact until 1970 until it finally collapsed. For decades, the area remained private. Because no access was allowed to anyone other than owners, Ruby has suffered a few indignities of vandalism and theft often found in other ghost towns.

Today, Ruby remains private, owned by a couple of families working to preserve the town and make it a recreational area. The good news is they now allow visitors. The old settlement continues to boast more than two dozen buildings. Only Vulture City rivals it in the number of remaining structures in a ghost town mining camp.

Today’s more interesting structures include the school, which continues to display its chalkboards and some furnishings; the jail, mine offices, warehouse, head frame, the infirmary, and several homes.

Two small lakes created by the dam remain shining blue against the mountains and are surrounded by shifting sands created from the many tailings of the area. It’s a beach oasis in the middle of the desert. Across the sand dunes is an old cemetery.

The hill behind the warehouse is unsafe for hiking, filled with collapsing mining shafts below the ground. The main shaft extended some 700 feet during the mining heyday, with lateral bores heading out some 2,000 feet at various depths. Over the years, water erosion has added to the instability, and large cave-ins have occurred across the mountainside.

During our visit in 2007, work continues in the town of Ruby to stabilize its remaining buildings, which would continue far into the future. A perimeter fence erected around the site has resulted in a noticeable improvement in the water quality of Ruby’s two small lakes, as cattle are prevented from entering the site. Though the lake has never been stocked, it does provide some fishing opportunities, as visitors have pulled out bluegill, catfish, and largemouth bass.

A Colony of Mexican free-tail bats, numbering an estimated 1.5 million, makes their home in Ruby’s abandoned mine shafts from May to September. It is a sight to see during the summer as they emerge en masse at sundown from the mine.

Ruby, Arizona, is about 30 miles west of Nogales and four miles north of the Mexican border. To get there from Nogales, take I-19 north to Ruby Road/AZ-289 West, exit 12. Follow 289 for some 10 miles before arriving at the townsite. Much of the road is unpaved, winding, and can be treacherous. A high-clearance vehicle is recommended.

For information on fees, camping, fishing, and more, see Ruby’s official website.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2023.

See our Ruby Photo Gallery

Also See:

Phoenix to Nogales (Travel Blog)

Arizona Ghost Towns and Mining Camps

Arizona Ghost Town Photo Galleries

Arizona – The Grand Canyon State

Is Ruby Haunted?

With its bloody history, it would come as no surprise if this old ghost town is haunted. But, search as I might, I could find no stories or tales of any spiritual goings-on there. Well, one old legend tells of the mercantile having been built over an old padre’s grave. After the first double murder, while a police officer was investigating, he was told by an old-time local that there was a curse on the building. The old-timer explained further: “Old Tio Pedro died years ago. He predicted evil for the occupants of the post office ’cause it was built over an old padre’s grave.” The investigator confirmed the superstition with the local peace officer, who informed the investigator that the legend was common among the Mexicans in the area.

Perhaps there was something to the superstition, as murder and mayhem were not yet over at the Ruby Mercantile. The store was sold, and the next occupants of the building were also killed a year and a half later.

While I don’t consider myself a ghost hunter, it seems that I frequently “run into” them, whether it’s a story or tale I read or hear about or, on a rare occasion, a “glimpse” of one. In any event, we had roamed the Ruby buildings for about an hour, and as we made our way back out, we stopped at the old Ruby school along the way.

A fascinating building that still holds its historic chalkboards, as well as some furnishings, I was immediately hit “in the chest with a feeling of a presence. When I do “glimpse” a ghost, this is usually the way it first portrays itself – with an extremely heavy feeling in the chest. I walk into the next classroom, where Dave snaps photos when we hear footsteps in the other room. But, when we quickly return, there is no one there. Suddenly, the footsteps and sounds begin again in the room we just left. Again, no one was there.

Because my focus is not on the ghosts but rather on the ghost town, I would ordinarily let this drop. However, the feeling is so intense I insist on going back and talking to the caretaker. Have they heard of a ghost in the schoolhouse? Dave argues, “They’re going to think you’re crazy.” Oh, well. I forge forward. No stories of ghosts in the schoolhouse. In fact, the only thing that has been heard is a story of a long-dead old miner that has made himself known.

But, I am sure that something unnatural was in that schoolhouse, which happens to be close to the old Ruby Mercantile. The presence, however, didn’t feel “malevolent,” just there.

In any case, it was interesting, and I’m now wondering if anyone else has any tales of Ruby ghosts.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2023.

Also See: