~~~~

Perched high atop Cleopatra Hill overlooking the Verde Valley is the historic mining camp of Jerome, Arizona. Once a thriving copper mining town, Jerome has survived by becoming a mecca for artists and tourists.

Like most places in Arizona, the area was first inhabited by Native Americans, as far back as 1100 A.D. There were several groups of ancient Indians that thrived in the Verde Valley, including the Hohokam tribe and later the Sinagua at Tuzigoot. The Mogollon and Saluda occupied nearby regions of Arizona during much of the same time. By the early 1400s, the Sinagua Indians had abandoned the valley, but no one knows exactly why. By the time the Spanish explorers came to the region in 1582, the Yavapai Indians were settled there.

Always on the lookout for precious metals, the Spanish enticed the Yavapai to lead them to their mine, which was little more than a 16-foot cave-like pit in the area that is now Jerome. The Yavapai used the copper metal for die to paint their faces, clothes, and blankets. But, the Spanish weren’t interested in copper. In their quest for gold and silver, they soon abandoned the Indians. Through the years, a few lone prospectors worked in the area, but the Indians were left relatively alone until the 1850s. After the Mexican-American war ended in 1848 and the region became part of the United States, more and more Anglo-Americans began to settle the area. In came ranchers, homesteaders, and more prospectors. In 1863, gold was discovered near Prescott and thousands of miners flooded the region.

In an attempt to protect themselves from the encroaching white settlers, the Yavapai, who had previously been peaceful, began to band together in an attempt to safeguard their land and food supplies. Hostilities broke out between the Indians and the settlers. After the Civil War, the U.S. Cavalry was sent in to subdue the Indians until the Yavapai were completely defeated by General George Crook in the fall and winter of 1872-1873. What was left of the tribe was sent to the Camp Verde Reservation and later to the San Carlos Reservation.

By the 1880s investors began to see the potential in copper and a number of mines were established, including the United Verde Copper Company in 1882. Owned by Territorial Governor, Frederick Tritle, the governor obtained financing from New York investors, James McDonald and Eugene Jerome, for whom the town was named. The town boomed for the next year until the price of copper plummeted and the mine was forced to close. Though it caused a number of people to leave, the town hung on and continued to grow slowly. By September 1883, a post office was established, which has never closed.

In 1888, William A. Clark, who had long owned several claims in the area, bought the United Verde Copper Company for $80,000.00. The ingenious entrepreneur began to make a number of improvements, including bringing in a narrow-gauge railroad from Jerome Junction, that connected with Ash Fork, and eventually the Santa Fe, Prescott, & Phoenix Railroad. The narrow-gauge line operated from 1895 to 1920, making its way through 187 curves and 28 bridges on its 27-mile run.

Over the years, Clark expanded his operation with a surface plant in Jerome, a tunnel transfer system known as the “Hopewell Tunnel,” new loading facilities at Hope, and more standard gauge railroads. Within seven years of purchasing the United Verde Copper Company, Clark was netting some $1 million per month in revenue.

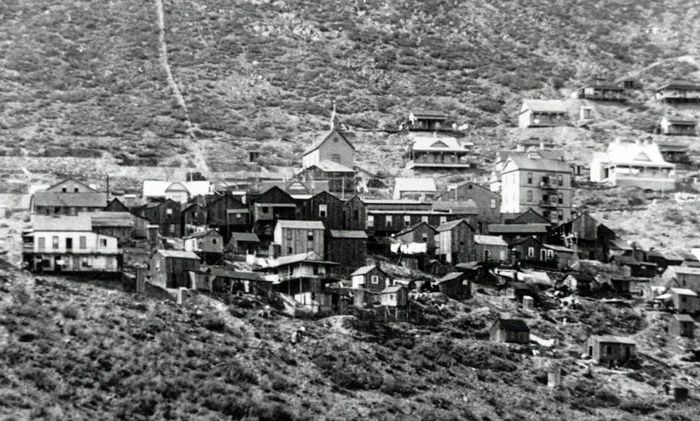

In the meantime, the town of Jerome was bustling and by 1899 had become the fifth-largest city in the territory. The same year, the town was incorporated, with one of its primary focuses being to specify building codes.

Requiring brick or masonry construction, the laws were instituted to end the frequent fires that plagued Jerome previously. Filled with wooden buildings, two blocks of the commercial district burned in 1894 and more fires blazed businesses in 1897, 1898 and 1899. One interesting tale of the 1897 fire was when a madam of one of the local brothels ran into the street in a panic, offering free “business” to the entire fire department from then on if they would save her house. Not surprisingly, the house was saved.

Typical of many bustling mining camps, Jerome quickly gained a reputation of a rough and rowdy town, with its many saloons, gambling dens, and brothels, so much so that on February 5, 1903, the New York Sun proclaimed Jerome to be “the wickedest town in the West.”

Though incorporating the town brought official organization, a fire department, and a police force, it didn’t slow its vices and wicked reputation. In fact, the chaos increased with even more prostitution, alcohol, gambling, drug abuse, and gunfights in the streets as the population continued to grow.

Continuing to expand and improve his mining operations, Clark began building another railroad in 1911, which connected the Verde Valley to Drake, Arizona. Spending some $1.3 million dollars to build the 38-mile Verde Valley Railroad, the line, operated by the Santa Fe, Prescott & Phoenix Railroad was built in just one year.

A miracle of engineering, it took 250 men, 200 mules, and hundreds of pounds of explosives to lay the rails. Still operating today, the Verde Canyon Railroad provides a four-hour scenic train ride through the towering red rock pinnacles of Verde Canyon, through two national forests, passes by Indian ruins, and through a 680-foot man-made tunnel.

When World War I began, the price of copper soared and it was then that the town really boomed, boasting some 15,000 people. From all over the world, immigrants came to the copper mines that were operating 24 hours a day. A number of hotels were built for the sole purpose of housing the miners, who often rented them in eight-hour shifts. Many of the town’s businesses also operated around the clock – especially those of the more “shady” variety – including eight brothels, 21 saloons, and numerous and opium dens. However, the more “civilized” folk also built three movie theaters, schools, swimming pools, bowling alleys, restaurants, churches, and an opera house.

Though the town was thriving, a cauldron of dissatisfaction was also boiling. The miners were getting extremely unhappy about pay and working conditions in the mines. Union organizers were active, especially that of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), most often called the “Wobblies.” This group, who had been widely loathed by middle-class America, became much feared and hated at the outbreak of the war because many of their members were foreign and they posted a threat to the social and industrial order. They were also found to be “suspicious” simply because they were “Easterners.”

Though the non-miners may have been suspicious, the miners joined the union in waves and by May 1917, strikes were in full force in all of the mines in the Jerome area, and a month later, they had spread statewide. But the mine owners in Jerome were having none of it. On July 12th, armed agents of the mine owners roughly rounded up some 67 labor union organizers and unionized miners on a railroad cattle car and shipped them to Kingman, Arizona, warning them not to return if they valued their lives, an event that became known as the Jerome Deportation.

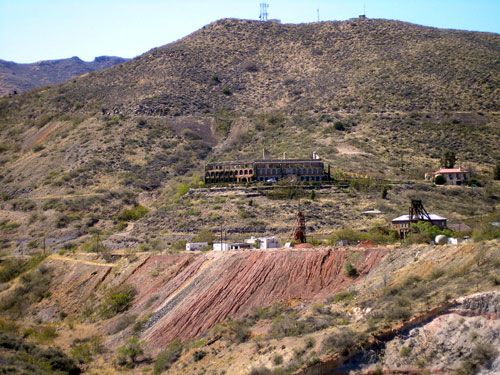

After the war, the price of copper ore began to decline and had become harder and harder to extract from the mountain. By the time the Great Depression began, Jerome, along with the rest of the nation was in a full-blown depression and by 1930, the mines had closed. However, in 1935, Phelps Dodge bought up the vast majority of mining operating in the area and began to mine again, this time on a larger scale, using tons of explosives and creating a huge open-pit just north of the town. Using a full-scale underground railroad, the ore was moved to a new smelter in Clarkdale. The constant blasting and tunneling below the surface of the mountain had a dire consequence on the city of Jerome, as the town began to slide down the hill. Some businesses, including a movie theater, pharmacy, pool hall and JC Penney’s made an unwanted move. Other businesses simply crumbled. Jerome’s famous “Sliding Jail” can still be seen hundreds of feet downhill from its original location.

But the hardy residents of the town continued to “hang on” and when WWII, copper prices increased once again, putting the town “back in business.” But, the rich copper ore was dwindling and getting even harder to get to. After the war, prices dropped once again and finally, in 1952, Phelps Dodge closed its operations in Jerome forever. During its 70 years in operation, the United Verde Mine and others in the area produced in excess of $1 billion in copper, gold, silver, zinc, and lead.

With no work, families moved in the masses. Many, with no buyers for their homes, simply left them, complete with furnishings, before making their way on to other opportunities. With only about 100 residents left in the town, buildings began to deteriorate, continued to slip down the hill, or suffered vandalism over the next two decades, despite the efforts of the Jerome Historical Society.

However, in the late 1960s, new residents, enchanted with the old town, began to move in once again. It soon developed into an artists’ community and tourist destination. On April 19, 1967, the Jerome Historic District was officially designated a Registered National Historic Landmark and “That the past may live” became the town’s official motto.

The town began to promote itself as America’s newest and biggest ghost town and more and more tourists began to visit, with some deciding to make it their home, gradually increasing the town’s population.

Today, this quaint town of about 400 residents provides tourists with not only a view of the past in its numerous historic buildings, but also a number of specialty shops, restaurants, and galleries. Take a walking tour of Jerome, where you’ll see restored historic structures and others with plans for restoration.

One interesting area is the “Crib District” across the street from the English Kitchen, in a back alley where all the buildings were are part of Jerome’s ill-famed “prostitution row. Air-conditioning is provided by Mother Nature, as the temperatures in Jerome are about 20 degrees cooler than in the Verde Valley.

In addition to its many photo opportunities, Jerome provides a number of attractions including the Douglas Mansion State Park, a 1916 mansion and museum; carriage tours, and the Jerome Historical Society Museum. Nearby, ride on the Verde Canyon Railroad, some ten minutes away; the Blazin’ M Ranch, a family entertainment center in Cottonwood; and the Tuzigoot National Monument, a 12th-century Indian village.

Haynes and the Gold King Mine

Just about a mile north of Jerome is another old mining camp called Haynes. In 1890, it was the home of the Gold King Mine and a bustling suburb of Jerome. Astride one of the richest copper deposits in history, the Haynes Copper Company sank a shaft 1200 feet into the mountain. Though they didn’t find copper, they got even luckier and discovered gold. In 1901 it boasted a population of 301 people. Even though it was so close to Jerome, it boasted its own post office from 1908 to 1922.

But, for Haynes, like Jerome and other area mines, the ore wouldn’t last forever. By 1914, it was called home to only 14 people and soon emptied out completely. In the 1960s it was sold and turned into a “ghost town” tourist attraction. Today, it is filled with a number of old buildings, a petting zoo, a walk-in mine, antique vehicles, and old machinery, much of which still operates today.

Of the buildings, some are original including the 1901 blacksmith shop, the clapboard hilltop home, which was once used as a boarding house and served a short stint as a bordello; and a 1914 sawmill that still fills lumber orders. Other buildings were brought in from the area, and some were reconstructed utilizing old lumber. The “town” provides demonstrations of antique mining equipment, the world’s largest gas engines, features dozens of classic cars and trucks, and provides a billion-dollar view of the Verde Valley.

Haynes is located at 1000 Perkinsville Road just north of Jerome. If this isn’t enough to arouse the usual tourist’s interest, it should come as no surprise that Jerome is allegedly haunted. But that’s a whole ‘nother story. Click HERE!

Jerome, Arizona is located between Prescott and Flagstaff on AZ Alternate 89.

© Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated September 2022.

See our Jerome-Haynes Photo Gallery HERE

Also See: