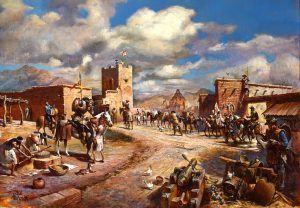

The Presidio of San Ignacio de Tubac, also called Fort Tubac, was a Spanish-built presidio established by the Spanish Army in 1752 at present-day Tubac, Arizona. For some 50 years prior, the Catholic Church and the Spanish military had been the vanguards of Spanish frontier expansion throughout New Spain. The Jesuit explorer, Eusebio Francisco Kino, established missions from 1687 to 1711 to Christianize and control the native peoples in the area. He established the Mission San Cayetano de Tumacácori nearby in 1691. At that time, Tubac was a small Piman village, which soon became a mission farm and ranch. In the 1730s, Spanish Colonists began to settle the Tubac area, irrigating and farming the lands along the Santa Cruz River and raising livestock.

However, many of the native peoples in the region were not happy with their gradual loss of autonomy and territory. In addition, several treaties that allowed the Spanish to mine and herd on Native lands led to an influx of new settlers that often culminated in low-level violence by the local Spanish settlers against Indians. As a result, a Pima chief named Luis of Saric, stirred by many grievances, led a bloody uprising, known as the Pima Revolt, in November 1751, destroying the small settlement at Tubac.

Following a significant battle and the subsequent surrender of the Piman Indians, the Spanish founded the Presidio San Ignacio de Tubac in June 1752. Located about four miles north of the Tumacacori Mission, a garrison of 50 soldiers, commanded by Captain Juan Thomas de Belderrain, were made responsible for protecting the Tumacacori and Guevavi Missions, the Rancheria of Arivaca, and even points as remote as San Xavier.

The first Spanish colonial garrison in Arizona, the area was constantly under attack by hostile Apache Indians. However, by 1766, the post still held some 50 officers and soldiers, and by that time, about 40 families had settled around the presidio. The following year, the Jesuits were expelled from Spanish possessions in 1767 and were replaced by the Franciscans.

PerhapsTubac’ss most famous person was soldier and explorer Captain Juan Bautista de Anza II, who had joined the volunteer soldiers during the Pima Revolt. By the time he was 19, he had been promoted to a lieutenant serving at the Presidio in Fronteras, just across the present-day international border south of Douglas, Arizona. When his commander died suddenly in 1759, he became the Captain of Presidio of San Ignacio de Tubac. He led the defense of the royal settlements and presidios against the Apache and Seri Indians until 1773. In 1774, he asked permission to prove that a land route from Tubac to Monterey in Alta California was possible. The Viceroy of New Spain, Don Antonio Bucareli, granted him this assignment.

On January 8, 1774, Captain Juan Bautista de Anza, along with three Padres, 20 soldiers, 11 servants, 35 mules, 65 cattle, and 140 horses, and a guide set forth from the Tubac Presidio. The expedition took a southern route along the Rio Altar (Sonora y Sinaloa, New Spain), then paralleled the modern Mexico/California border, crossing the Colorado River at its confluence with the Gila River. De Anza reached Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, near the California coast, on March 22, 1774, and Monterey, California, AltaCalifornia’ss capital, on April 19. He returned to Tubac by late May 1774.

A few months later, in October 1774, De Anza was promoted to lieutenant-colonel and ordered to lead a group of colonists to Alta, California. The expedition got underway in October 1775, with several hundred colonists from the provinces of Sinaloa and Sonora, along with 60 from Tubac. Over 1,000 head of cattle, horses, and mules were also gathered to transport food supplies and tools, provide food on the journey and establish new herds once the colonists settled at their new home on the Pacific. The group arrived at Mission San Gabriel Arcángel in present-day Monterey, California, in January 1776, having suffered greatly from the winter weather en route. Leaving the colonists at Monterey, De Anza continued north as far as present-day San Francisco, where he selected sites for the mission and presidio.

FollowingAnza’ss return to Tubac, military authorities moved the garrison from Tubac to Tucson in 1776, and many of the unprotected settlers abandoned their homes. Under Lieutenant Juan Fernandez Carmona, the force was enlarged to 56 officers who would construct Presidio San Augustin del Tucson.

For a decade, Tubac languished from Apache depredation and without military protection. The situation finally resulted in the Viceroy’s reactivating the presidio in 1787, with Pima Indian troops and Spanish officers. In 1804, the post had two officers, two sergeants, and 84 men. There were also eight families of Spanish settlers and 20 Indian families living within the presidio land allotment of five square miles. The garrison community had 1,000 head of cattle, 5,000 sheep, 600 horses, 200 mules, 15 burros, 300 goats, and an annual harvest of 1,000 bushels of wheat and 600 bushels of corn.

When Mexico won her independence from Spain in 1821, a new flag would fly over Tubac. However, hostile Apache Indians attacked the settlement repeatedly in the 1840s, and in 1848, after a fierce Apache assault caused great loss of life Tubac was again abandoned. This catastrophe, coupled with the drain of men leaving for the goldfields of California in 1849, turned Tubac into a virtual ghost town. For a short while in 1846, during the Mexican-American War, Tubac was home to a large company of Mexican troops, over 200 men. After the war, Tubac was abandoned until Americans traveling for the California Gold Rush decided to settle there instead.

With the Gadsden Purchase of 1853, ratified by the American Congress in 1854, all of Arizona south of the Gila River became the property of the United States. Before long, a survey was sent out, and a member of the survey party wrote: “Tubac is a deserted village. The wild Apache lords it over this region, and the timid husbandmen dare not return” to their homes.

In 1854 Charles D. Poston and his associates began searching for gold and silver in the Tubac region. After the eastern capital was obtained, the Sonora Exploring and Mining Company was incorporated, and Tubac was set up as field headquarters in 1856. Soon, the great Heintzelman silver mine, about 14 miles northwest, was opened, and the Arivaca, Sopori, and Santa Rita mines were being developed, all within a 20-mile radius of Tubac.

Poston, a natural organizer, with a group of vigorous young men accompanying him, soon made the town a young frontier metropolis, which boasted around 2,000 people at its peak. At that time, it was the largest town in Arizona. On March 3, 1859, Arizona’s first newspaper, “The Arizonia” received its first printing in Tubac. However, Tubac was destined for a short life as a mining metropolis. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, much of the defensive manpower in the frontier was drained away, and the Apache were quick to move back in with their attacks. By the end of the year, Tubac was abandoned.

In 1864 Tubac was visited by J. Ross Browne, a traveler and writer. He said Tubac was completely abandoned, with roofs of the adobe houses falling in and walls crumbling to ruins. Although the region was resettled after the war, silver strikes in the Tombstone area and the routing of the railroad through Tucson drew development interests away from Tubac, and the town never regained its earlier importance.

The Presidio of Tubac was resettled in the 1880s, and by the time Geronimo surrendered in 1886, the Apache were no longer a threat to settlers in that part of Arizona.

Today the town of Tubac is best known as an artists’ colony. The ruins of the presidio and two original presidio buildings can be seen at the Tubac Presidio State Historic Park. The Park features a museum, an underground display of the Presidio ruins, Arizona’s first printing press, an exhibition of paintings of Arizona history by William Ahrendt, a picnic area, and the Juan Bautista de Anza Trailhead. It also features the 1885 furnished schoolhouse, Otero Hall, and the Rojas House — all on the National Register of Historic Places.

Contact Information:

Tubac Presidio State Historic Park

1 Burruel Street,

Tubac, Arizona 85646

(520) 398-2252

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2022.

Tubac Presidio

Also See:

Sources:

Arizona State Parks

National Park Service – Tumacacori

Tubac Presidio State Historic Park

Wikipedia