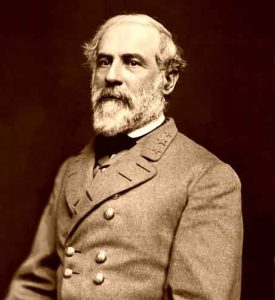

Appomattox Court House National Historical Park in south-central Virginia commemorates the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia to Union Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant on April 9, 1865. For four years, the North and South, the United States of America, and the Confederate States of America had been engaged in the bitter and terrible Civil War. The surrender concluded the bloodiest war the United States has ever had; the victory of the Union over the Confederacy sealed the fate of the institution of slavery and ended the question of secession.

In March 1865, Confederate General Lee retreated from Petersburg and Richmond, across southern Virginia, with Union forces in relentless pursuit.

As the sun rose on April 9 in Appomattox, General Lee still clung to the belief his war was not over. Eight thousand men from Major General John B. Gordon’s Second Corps, along with Lee’s nephew Fitzhugh Lee and what remained of the Confederate cavalry, were lined up for battle just west of the village of Appomattox Court House. Robert E. Lee hoped there was only a thin line of Union cavalry ahead of him that he could smash through, find supplies and rations, and then turn south to march to North Carolina to continue the fight. For a week, General Ulysses S. Grant had thwarted Lee’s plans to turn south, actively blocking Lee’s movements trying to surround his forces. As a result, Grant’s forces finally got ahead of Lee at Appomattox, and Lee found himself in the middle of the fight. Lee’s headquarters were east of the village near the center of his army. Gordon’s Second Corps and the Cavalry were west of the village, readying for a fight, and Longstreet’s command, the First Corps and Third Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia were in the east guarding the rear.

Lee knew more Federal troops were approaching from the east and perhaps the south, and he hoped he could move his army before the Federal reinforcements arrived. However, Lee’s hopes were dashed by the arrival of thousands of Union infantry, including United States Colored Troops, who had marched most of the night to block the way. By 8:00 a.m., Gordon’s men retreated toward the village, Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry was fleeing toward the west, and Lee knew his war was over.

In the meantime, Grant had ridden west all morning toward the fighting, knowing he was drawing near to the end of the Army of Northern Virginia. On April 7, after the Confederates had suffered a catastrophic defeat at the Battle of Sailor’s Creek, Grant asked Lee to surrender and declared any “further effusion of blood” was solely Lee’s responsibility. Lee, still believing he could escape, declined to surrender but did ask about the possibility of a peace agreement. Grant tactfully replied that he could not discuss a peace agreement, but he could consider a military surrender. As he realized his army was cornered, Lee asked to discuss terms of surrender on April 9.

After getting word of Gordon’s retreat and the arrival of Federal forces to his rear, Lee rode east, believing Grant would be there to meet him. When Lee arrived at his rear lines, Major General Gordon sent word to him that Grant was on the move and could not be reached immediately. Lee sent out two letters to Grant, one through General Gordon Meade’s lines in the east and one through General Philip Sheridan’s lines to the southwest of the village. Grant had been riding all morning to reach Sheridan’s forces and was south of Lee’s army in the outskirts of Appomattox County when the message intercepted him. Grant wrote in his memoirs that the migraine, or “sick headache” he had been suffering from all night, immediately disappeared when he received Lee’s letter agreeing to surrender. Grant sent a reply with one of his staff officers, Orville Babcock, agreeing to meet and telling Lee to select a meeting site.

After some difficulty and confusion, Babcock crossed into Confederate lines under a flag of truce, and he found Lee resting in an apple orchard near the village by the Appomattox River. Lee read Grant’s letter and sent his aide, Charles Marshall, into the village to find a suitable home for the meeting. Marshall’s account, written years later, is sparse on details, but it seems likely the McLean House was picked simply because Wilmer McLean was the first person he encountered. McLean may have been the only property owner who had not fled the village to avoid the fighting. McLean showed Marshall an abandoned, unfurnished building first, but Marshall rejected it as unsuitable. Only then did McLean offer the use of his home.

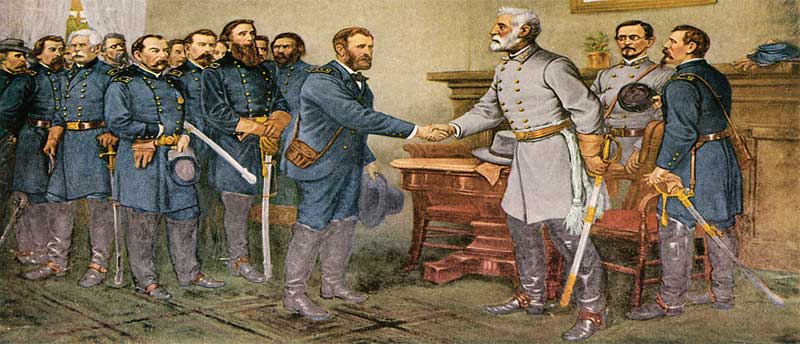

Lee arrived at the McLean House sometime after one o’clock and waited with Marshall and Babcock. Grant and his staff arrived at McLean’s parlor half an hour later. Grant was uncertain how to bring up the subject of surrender, so after introducing his staff and the army commanders with him, he brought up the Mexican-American War and the brief meeting the two men had then. Eventually, Lee said they should get to the business at hand. Grant quickly wrote out the terms in his order book, which had already been outlined for Lee in the letters the two generals exchanged over the two previous days.

Aside from Grant and Lee, only Lieutenant Colonel Marshall and perhaps a half dozen of Grant’s staff officers were present for most of the meeting. Approximately a dozen other Union officers entered the room briefly, including Captain Robert Todd Lincoln.

Few besides Grant left detailed accounts of what transpired, and while some accounts disagree on the details, there are many key consistencies. The heart of the terms was that Confederates would be paroled after surrendering their weapons and other military property. If surrendered soldiers did not take up arms again, the United States government would not prosecute them. Grant also allowed Confederate officers to keep their mounts and sidearms.

Lee appeared relieved by the terms. Grant said he could not tell what Lee was thinking, but some indication of his anxiety might be inferred. When Lee dressed in his finest uniform that morning, he indicated to his staff that he expected to be taken prisoner and wanted to be in proper form and “make his best appearance.”

Although Lee agreed to the terms, he asked if his men could keep their horses and mules in the cavalry and artillery. The Confederate army provided weapons and military property, but the men provided their own mounts. Grant indicated he would not amend the terms but would issue a separate order allowing that to happen. Lee said he thought that would have a happy effect on his men. Lee and Grant also agreed to appoint three officers from each army to act as “commissioner” for the surrender who would work out the details of issuing parole passes, returning Union prisoners the Confederates had captured, and sending rations from Union lines to Confederates. Over the next few weeks, additional Confederate forces surrendered using Grant’s terms for Lee as a template.

By 3:00 p.m., the formal copies of the letters indicating the terms and acceptance of the surrender were signed and exchanged, and General Lee left the McLean House to return to his camp. Grant and his staff followed him and removed their hats as a respectful, farewell gesture that Lee returned before riding down the stage road.

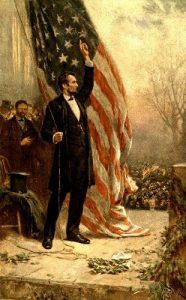

Grant met with his staff and commanders briefly before leaving for his temporary headquarters a short distance west of the village. Grant sent a message via the newly repaired telegraph lines at Appomattox Station to President Abraham Lincoln that Lee had surrendered. Within hours the news was being shouted in the streets in Washington, D.C.

The six commissioners for the surrender met that evening in the McLean House. They had to bring a table with them since the room had been largely stripped bare by Union officers purchasing or otherwise acquiring souvenirs from the McLean’s home. In this “commissioners’ meeting,” they worked out the details of supplying the Confederates, printing and signing paroles, and the format for the formal surrender of weapons, flags, and other military property. Under the supervision of Major General George Sharpe, around 30,000 parole passes were printed in the Clover Hill Tavern, and 28,231 paroles were issued to the Confederates between April 10 and April 15.

On April 10, Grant met briefly with Lee on the village’s eastern edge. Grant hoped to persuade Lee to influence other Confederate forces to surrender, but Lee refused. Grant left Appomattox to continue the work of ending the war. Lee returned to his headquarters, where he tried to remain isolated, refusing to meet with most Union officers who wanted to speak with him.

The same day, Lee directed Lieutenant Colonel Marshall to write a farewell address to the Army of Northern Virginia, what became General Order No. 9. In this last formal address to the Army of Northern Virginia, Lee took responsibility for deciding to surrender to spare further suffering to his men, who he then praised for their “constancy and devotion” to the Confederacy. Lee attributed the Confederacy’s defeat to being “compelled to yield to overwhelming numbers and resources.” Lee was unapologetic for fighting the war, and he only seemed to have regretted letting his men down. Lee stayed in Appomattox until April 12, the day of the formal infantry surrender ceremony and the fourth anniversary of the first shot at Fort Sumter that started the conflict. By April 13, Confederate troops had stacked their arms along the Richmond-Lynchburg Stage Road, were issued paroles, and were allowed to return to their homes.

The war ended for Abraham Lincoln three days later when John Wilkes Booth assassinated him on the evening of April 14.

On April 26, near Durham, North Carolina, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston surrendered to Union General William T. Sherman. By May 26, Confederate forces in the Trans-Mississippi west had given up the fight. The example set by Robert E. Lee at Appomattox was thus repeated wherever Confederate troops remained in the field and led to the systematic “Reconstruction” across the South.

“Thank God that I have lived to see this! It seems to me that I have been dreaming a horrid dream for four years, and now the nightmare is gone.” — Abraham Lincoln, April 3, 1865, after learning of the Federal occupation of Richmond and Petersburg and the pursuit of Lee

Appomattox symbolized the promise of national reunification, a first step on the long road to dealing with sectional divisions. However, this ideal was not always supported by reality as African Americans struggled for equal rights ostensibly guaranteed through newly ratified constitutional amendments. White Southerners coped with economic and political dislocations and feelings of submission, humiliation, and resentment.

In the fall of 1867, the McLeans left Appomattox Court House and returned to Mrs. McLean’s family estate in Prince William County, Virginia. In the following decades, the property changed hands numerous times.

On April 10, 1940, Appomattox Court House National Historical Monument was created by Congress to include approximately 970 acres. In February 1941, archeological work was begun at the site, then overgrown with brush and honeysuckle. Historical data was collected, and architectural working plans were drawn up to begin the meticulous reconstruction process. The whole project was brought to a swift stop on December 7, 1941, with the bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japanese forces causing the United States entry into World War II.

On November 25, 1947, bids for the reconstruction of the McLean House were opened, and on April 9, 1949, 84 years after the historic meeting reuniting the country, the McLean House was opened by the National Park Service for the first time to the public. At the dedication ceremony on April 16, 1950, direct descendants of Robert E. Lee and Ulysses Grant cut the ceremonial ribbon as an audience of approximately 20,000 looked on.

Appomattox Court House is an unpretentious village on a windswept ridge in south-central Virginia. Unlike such well-worn tourist paths as Fredericksburg, Vicksburg, or Gettysburg, where history is a mantle proudly worn, Appomattox is a quiet spot that maintains its importance with patient dignity.

The park encompasses approximately 1,700 acres of rolling hills in rural central Virginia. Thirteen of the buildings that existed in April 1865 remain in the village today, while 14 other structures, including the McLean house, where the surrender took place, have been reconstructed on the original sites. It also features the original 1819 Clover Hill Tavern, where paroles were printed for Lee’s army, and the village of Appomattox Court House, the former county seat for Appomattox County. The reconstructed courthouse functions as the park visitor center. The village offers an immersive experience of a rural town of its time, with country lanes and fields that allow visitors to walk among historic homes, fenced yards, and outbuildings, including the tavern, jail, and store, small family burial plots, and orchards.

The village and other historic resources are preserved in much the same appearance they presented in 1865-1870. The main street circles the Courthouse, and the other buildings are clustered around the village. While the village was a center for county government and contained the homes of judges, clerks, and small-business operators, it was also an agricultural community with field slaves. Retention of the open fields along Virginia Highway 24, a major two-lane highway that bisects the Park, is an important factor in interpreting the historic scene resembling that of 1865. This is accomplished by cattle grazing and crop rotation of grasses, corn, and hay.

But for the absence of normal village sounds — men and women going about their daily routines, children playing, an occasional wagon lumbering by, and the noise from chickens and livestock — it seems almost like a step back into the 19th century.

The park also includes the Battle of Appomattox Station site, April 8, 1865, and the Battle of Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, which led directly to the surrender.

The Park is located three miles northeast of the town of Appomattox in Appomattox County.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, December 2021.

Also See:

Eastern Theater of the Civil War

Travel Blog – Sweet Virginia, Saving our Nation More than Once

Sources: