The Apache Wars were a series of armed conflicts between the United States Army and various Apache nations fought in the southwest primarily between 1849 and 1886. However, minor hostilities continued until as late as the turn of the century. Though not always well known, this series of battles is the longest war in U.S. history.

Battles:

Apache War, NM – 1854

Battle of Cieneguilla, NM – 1854

Battle of Ojo Caliente Canyon, NM – 1854

Battle of the Diablo Mountains, TX – 1854

Battle of Pima Butte, AZ – 1857

Battle of Cookes Spring, NM – 1885

Battle of Cookes Canyon, NM – 1861

Battle of Pinos Altos, NM – 1861

Battle of Placito, NM – 1861

Apache Pass/Fort Bowie, AZ – 1862

Big Dry Wash , AZ – 1862

First Battle of Dragoon Springs, AZ – 1862

Battle of Mount Gray, NM – 1864

Battle of Fort Buchanan, AZ – 1865

Battle of Salt River Canyon (Skeleton Cave), AZ – 1872

Apache War Campaign – 1873 and 1885-1886

Battle of Sunset Pass, AZ – 1874

Battle of Fort Tularosa, NM – 1880

Battle of Hembrillo Basin, NM – 1880

Cibecue Creek, AZ – 1881

Battle of Carrizo Canyon, NM – 1881

Battle of Fort Apache, AZ – 1881

Battle of Devil’s Creek, NM – 1885

Battle of Little Dry Creek, NM – 1885

Battle of Skeleton Canyon, AZ – 1886

Historically, the Apache had raided enemy tribes and sometimes each other for livestock, food, or captives. Raiding in small parties for a specific purpose, the natives considered these raids different than warfare and rarely united to gather armies of hundreds of men. The first conflicts between the Apache and other people in the Southwest date to the earliest Spanish settlements. Years later, when the American Government began to relocate other Indian tribes onto Apache lands beginning in about 1830, it fueled more conflict. At that time, the typical raids and bonds among the tribes became more frequent and more pronounced.

The first conflicts of the Apache Wars began during the Mexican-American War, beginning when American troops erroneously accused Cochise and his tribe of kidnapping a young boy during a raid. When Cochise truthfully said that they not kidnapped the boy and offered to find him for the Americans, the commander refused to believe him and instead took Cochise and his party hostage for the boy’s return. Cochise soon escaped, and a standoff developed as his Apache band and their allies surrounded the American forces, demanding the release of the rest of Cochise’s party. After the standoff, during which three additional braves and several American soldiers and postmen were captured, the Apache retreated, believing they were being flanked. In revenge for the troops’ refusal to release their people, the Apache killed the soldiers and postmen they had captured. The Army then killed the six men they had captured but allowed the women and children to go free. Unfortunately, three of the men killed were Cochise’s brother and nephews, and Cochise gathered the Apache tribes and made war on the United States, sparking the Apache Wars.

Upon the United States’ victory in the Mexican-American War in 1846, the United States inherited conflicts between American settlers and Apache groups. These conflicts continued and became more brutal once United States citizens began to encroach upon traditional Apache lands.

As a result, the United States Army established several forts to control the Apache bands, and several reservations were created. In the beginning, the goal of the Apache Wars was to quell tribal resistance against the occupation of Apache lands.

The first United States Army campaigns specifically against the Apache began in 1849, and the last major battle ended with the surrender of Geronimo in 1886.

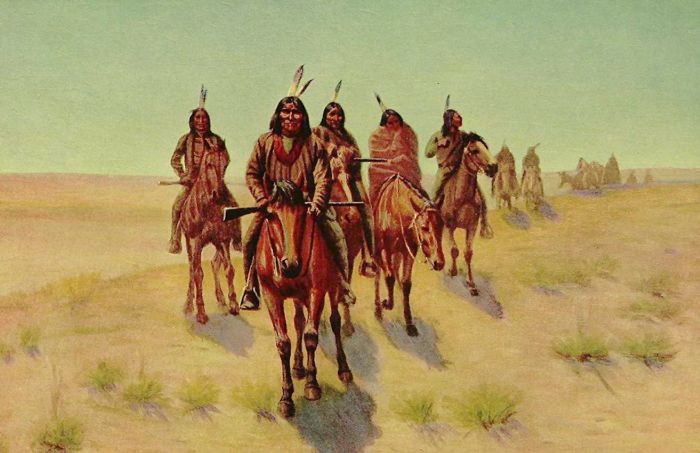

Apache leaders such as Mangas Coloradas, Cochise, Victorio, Juh, Delshay, and Geronimo led raiding parties against non-Apache. Now, they no longer raided in small parties but gathered armies of hundreds of men, using all tribal male members of warrior age. Fighting against them were such notable officers as General George Crook, Christopher “Kit” Carson, General William Tecumseh Sherman, and General Oliver Otis Howard.

Over the better part of three decades, Americans, both civilian and military, battled warriors of the Apache tribes in fights that stretched from southern Arizona to New Mexico and often across the border into Mexico. The fighting was unrelentingly savage, and the regular U.S. Army was ineffective for much of the war. Even during the Civil War, the Confederate Army briefly participated in the wars in the early 1860s in Texas before being diverted to Civil War action in New Mexico and Arizona. It was only after incorporating Apache scouts into the military, did the U.S. Army begin to make headway.

By the 1880s, many Apache bands had agreed to a negotiated settlement with the government and moved to reservations. However, some bands continued the warfare, and government officials often couldn’t distinguish between those who had settled and the Apache raiding parties. Consequently, the government response was sometimes heavy-handed, which resulted in more escalation of some Apache and drew others into the renewed conflict.

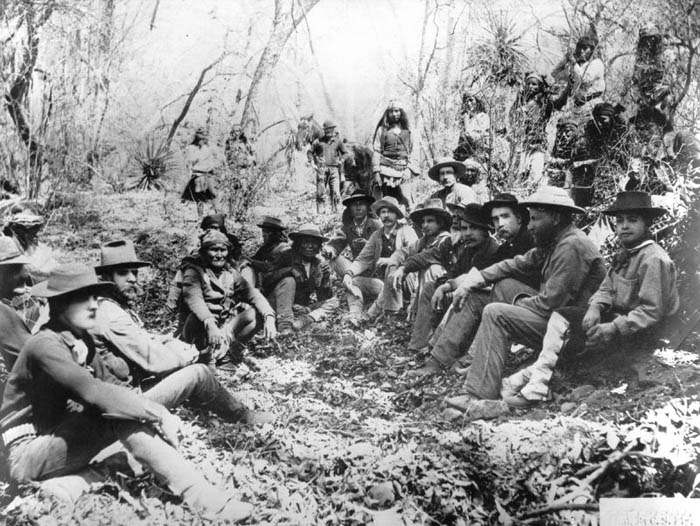

In 1886 the Army put over 5,000 men in the field to wear down and finally accept the surrender of Geronimo and 30 of his followers at Skeleton Canyon, Arizona, in the summer of 1886. This is generally considered the end of the Apache Wars, although conflicts continued between citizens and Apache for years.

After Geronimo surrendered, the 65-year-old war chief and his band were taken to Florida and would not reunite with their families for over two years. The first group of Chiricahua Apache who had been moved to Florida were already dwindling due to malaria. They were then moved to Mount Vernon in Alabama. In the meantime, their children were sent to schools in Pennsylvania to learn Christianity, English, and other American lifestyle aspects. After two years of imprisonment in Florida, Geronimo and his band were also moved to Alabama and were finally allowed to see their families once again.

General Crook suggested that the Chiricahua Apache be sent to live at the Fort Sill Reservation in Oklahoma, a more familiar environment. After eight years, the remaining 119 warriors who survived were finally sent to Oklahoma.

Geronimo would never again return to his native land but lived long enough to become an autograph-signing celebrity who rode in Theodore Roosevelt’s inaugural parade in 1905. Having once been known as the “worst Indian of all time,” Geronimo had become one of the most famous. He also toured the nation performing for fairs and exhibitions such as the Buffalo Bill Wild West Show.

After the Apache Wars were officially over, small Apache bands continued their attacks on settlements and fought United States Cavalry expeditionary forces and the local militia. The fighters were mostly warrior groups, with small numbers of noncombatants. In retaliation, soldiers searched and destroyed missions against the small bands, using tactics including solar signaling, wire telegraph, joint American and Mexican intelligence sharing, allied Indian scouts, and local quick reaction posse groups. Nonetheless, it was not until 1906 that the last groups of Apache, who had evaded the US Army’s border control of the tribal reservation, were forced back on the reservation.

During this conflict, the Apache suffered severe losses, including some 900 warriors who had died and thousands of others who lost land, homes, family, sustenance, and culture.

© Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated June 2021.

Also See:

Apache – Fiercest Warriors of the Southwest

Geronimo – Last Apache Holdout

Indian Wars, Battles & Massacres

Sources:

Hutton, Paul Andrew: Apache Wars, Crown, 2017.

National Park Service

Native Partnership

Wikipedia